Back in 2009, the New York Times published an article headlined “Recyclers, Scientists Probe Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” which noted that a group of scientists had “set sail from San Francisco Bay ... to study the planet’s largest known floating garbage dump, about 1,000 miles north of Hawaii.”

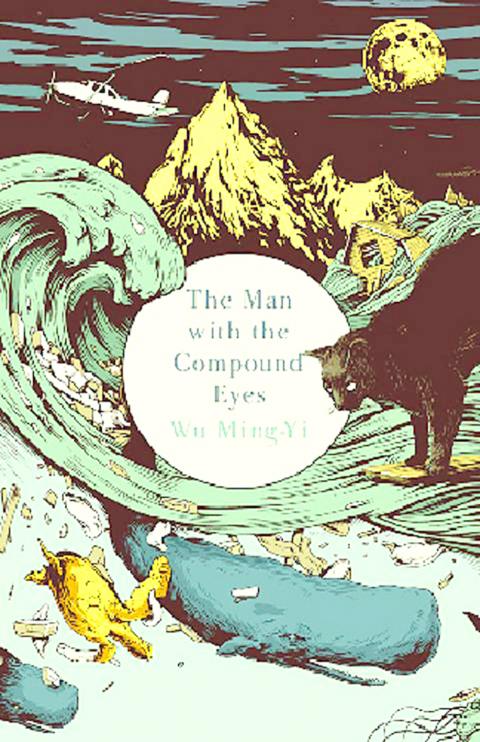

Fast forward to 2013: Taiwanese nature writer Wu Ming-yi (吳明益) has just released an English translation of his The Man with the Compound Eyes (複眼人) that’s aimed at an international readership. The 300-page novel, which has an eye-catching cover for the new British edition, is about that same floating dump.

Wu started writing the novel in 2006 when he read about the floating trash vortex in Chinese-language newspapers. As novelists often do, he concocted a “vision” based on the vortex: An Aboriginal teenager from the imaginary island of Wayo Wayo rides this garbage island and washes up with it one day on the east coast of Taiwan. In the ensuing chaos, the Taiwanese print and TV media have a field day reporting this ecological calamity, and Taiwan — the story is set in the near future of 2020 — is never the same.

In many ways, The Man with the Compound Eyes is a Pacific novel, about a Pacific Islander identity that differs in many ways from the commonplace Han Chinese-centric novels that are published in Taiwan.

The novel stars the boy from Wayo Wayo and a middle-aged Taiwanese college professor named Alice, both of whom are thrown into Taiwan’s east coast wilderness in a search for some lost hikers -- and enlightenment. There’s a cast of characters that expats will know well from their travels along the east coast, and Wu plots the story in very Taiwanese terms. (The English translation by Canadian expat Darryl Sterk, a professor at National Taiwan University, is superb and sensitively captures the nuances of Taiwan’s Aboriginal cultures and languages.)

Wu’s rollercoaster of a story is about wilderness, wildness, wonderment, love. It’s also about “massage parlors” along the east coast where tired and drunk soldiers go for rest and relaxation, with mini-lessons thrown in about various aspects of Aboriginal culture and food.

For readers in Taiwan who have been here for a number of years and know the east coast well, Wu’s novel is sure to strike a chord. But just how this Pacific novel will do overseas with readers in Europe and North America who know little about Taiwan or the Aboriginal cultures here remains to be seen.

As a longtime expat in Taiwan, I read the novel as a critique of modern society’s disregard for our planet’s ecology and environment — a wake-up call, in other words, for Taiwan and the rest of the world.

Readers overseas might find Wu’s story merely a pleasant diversion from the daily grind. You may not have to know much about Taiwan or insect eye biology to enjoy The Man with the Compound Eyes, and the mid-book chapters about that reveal the mystery behind the man with the compound eyes are perhaps the best writing to ever come out of a Taiwan novel. Some readers have drawn comparisons between the novel and Yann Martel’s Life of Pi. Yes, it’s that kind of book, and it would make that kind of movie, too.

Wu’s work began its literary life as a mostly-neglected, unheralded Chinese-language novel in 2011. Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture and the National Museum of Taiwan Literature (國立台灣文學館) used their resources and contacts to help set the book on its way to translation and overseas publication.

Published by Harvill Secker in London last month, the book will be released in New York in 2014, with a French edition as well. The US edition of the book, for reasons that only publishing and marketing industry executives know for sure, will not be released until next year. Readers in Taiwan and elsewhere who want to order the book can use the British Amazon Web site to purchase the UK edition.

Once I started reading this edition, I couldn’t put it down, and over the course of several days I felt that I had ventured into a new, uncharted territory concocted by a Taipei visionary. Part South American magical realism, part Margaret Atwood rollercoaster of the imagination, The Man with the Compound Eyes is a wild story that’s been mashed up into art, and you don’t need compound eyes to appreciate its unique vision.

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by