I HATE MUSIC, Superchunk, Merge Records

It’s one kind of victory for a long-running band to overhaul a sound; many do, or try to. (Innovation, it could be argued, is rock’s old European disease.) But it’s an equally valid kind of victory to make continually good records, the focus slightly tighter each time around. Persisting is creative, too.

I Hate Music, the indie-rock band Superchunk’s 10th album since 1989 and its second after a nine-year break from recording during the aughts, reflects an evolution almost like that of a group working the mainstream jazz language: refinement by slow degrees. The band’s connection to its core virtues has become at the very least a road map for getting older, at most a kind of ethical standard.

Superchunk knows where its power source comes from: the neat, fast eighth-note rhythm drive of Laura Ballance’s bass; the rush and thud of Jon Wurster’s drumming; the high, reedy, major-key emotiveness and strong melodic top lines in Mac McCaughan’s singing; Jim Wilbur’s consonant, note-bending guitar solos and feedback song-endings. The song structures on I Hate Music are pretty rear-guard; there’s not much here that couldn’t have lived in slightly different form — either slicker or rawer — on a college radio playlist in the ’80s.

It’s the sound of modesty in celebration mode, rock with a studied awareness of where the stresses should fall and where the notes should ring. But it’s rock against grandiosity. Over more than 20 years, with a few tentative exceptions, the band hasn’t done a fundamental, lasting rethink. It really likes its own ceilings.

References to travel and music, the practical life of a band, run through the lyrics; in Me & You & Jackie Mittoo, McCaughan asks “I hate music — what is it worth?” But he knows: It’s worth the pleasure of a passing thrill, like this song’s joyous chorus. Other passing thrills referred to here: summer baseball (Out of the Sun), navigating a foreign city (Trees of Barcelona), staying home (Staying Home). But really the songs seem to be about aging and maintaining relationships, with others and with one’s core self. They’re love songs about persistence, and that’s embedded in the sound of the record; you don’t need a lyric sheet to hear it.

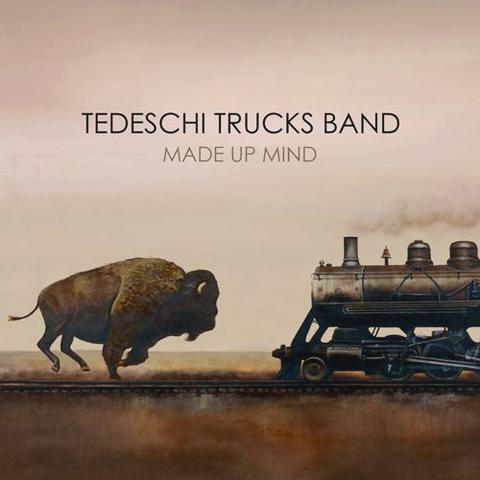

MADE UP MIND, Tedeschi Trucks Band, Sony Masterworks

When Susan Tedeschi has a target, she shines. When the target is herself, no one is safe. On Sweet and Low, from the new Tedeschi Trucks Band album Made Up Mind, she tries to slither her way back into the good graces of someone she’s wronged.

“I wasn’t always around, when you felt so low down/ She was your shoulder you cried on, when I weighed you down,” she confesses, her voice pulpy with regret. But she has a plan: Plead long enough, and “maybe you’ll crave a bittersweet melody.” She can’t right the wrong, and she can’t make herself right. It is what it is.

The best moments of this album — the group’s third, including a very good live release — are tragic in this way. Do I Look Worried is Tedeschi in full sass mode, and Misunderstood is her flaunting anguish. She is a determined, aggressive blues singer, and she only sounds right around pain, taking it in or doling it out.

Made Up Mind is another strong effort from the group headed by Tedeschi and her husband, the virtuoso blues guitarist Derek Trucks, though not quite as enlivening as its 2011 debut, Revelator. It’s a convincing band that jumps from rugged blues to Memphis soul to Muscle Shoals to Motown, full of technical savvy meted out judiciously.

While Tedeschi has a nasty howl, she’s not as effective when restrained; her power is in her texture, and her fearlessness in deploying it. Too often on this album, she aims to be gentle; it hinders her, and by extension, the band, which is built for live improvisation and jams, but which on record too often paints by numbers. That dynamic dulls a pair of loosely political songs — It’s So Heavy, about the depressing state of the republic, and The Storm, which is in part about Hurricane Sandy.

But when Tedeschi is given full rein, everyone follows suit, as on the horn-driven soul vamp All That I Need. And the title track is greasy and tart, with Trucks slathering urgent guitar while his wife plays the tease: I know you wish that you could see in my window/ Wishing you could pull up the blind/ And I’m wearing my robe made of flowers/ Just me and my made up mind.

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Aug. 25 to Aug. 31 Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household. In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized,

During the Metal Ages, prior to the arrival of the Dutch and Chinese, a great shift took place in indigenous material culture. Glass and agate beads, introduced after 400BC, completely replaced Taiwanese nephrite (jade) as the ornamental materials of choice, anthropologist Liu Jiun-Yu (劉俊昱) of the University of Washington wrote in a 2023 article. He added of the island’s modern indigenous peoples: “They are the descendants of prehistoric Formosans but have no nephrite-using cultures.” Moderns squint at that dynamic era of trade and cultural change through the mutually supporting lenses of later settler-colonialism and imperial power, which treated the indigenous as

Standing on top of a small mountain, Kim Seung-ho gazes out over an expanse of paddy fields glowing in their autumn gold, the ripening grains swaying gently in the wind. In the distance, North Korea stretches beyond the horizon. “It’s so peaceful,” says the director of the DMZ Ecology Research Institute. “Over there, it used to be an artillery range, but since they stopped firing, the nature has become so beautiful.” The land before him is the demilitarized zone, or DMZ, a strip of land that runs across the Korean peninsula, dividing North and South Korea roughly along the 38th parallel north. This