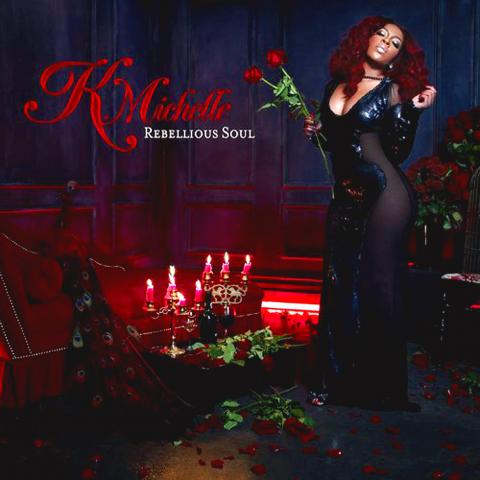

REBELLIOUS SOUL

K. Michelle

Atlantic

On the docu-soap Love & Hip Hop: Atlanta, which just completed its second season on VH1, K. Michelle is reliably pugnacious and routinely aggrieved. On a cast full of fighters — after all, these sorts of shows are nouveau soaps, modern pop operas — she stands out for her quick temper and willingness to rumble. It can be tough to remember behind all that pique is a boatload of genuine talent, looking for a way to break through.

The story of why K. Michelle has never capitalized on that tremendous promise has been partly told on the show — an earlier record deal was derailed by what she’s described as an abusive relationship with an ex, who was also in control of her career. Echoes of that story carom across Rebellious Soul, her debut album, a milestone it seems she might never have reached had she not been willing to put her dirty laundry up for public scrutiny on reality television.

The men on Rebellious Soul are lame, emotionally brutal and unaffectionate. On Can’t Raise a Man, she wails, “You wonder why he acts like a boy/ it’s ‘cause he wasn’t raised right before you.” On Hate on Her, she finds camaraderie in an unexpected place, another woman who’s been ruined by the same man: “I can’t even hate on her/ ‘cause I know you got no heart.”

K. Michelle’s early singles from her prior record deal — songs like Self Made and Fakin’ It — were raw and sassy, sung by someone not yet deflated by life’s sharp corners. Rebellious Soul has no such swagger. Instead, it has the confidence of survival. K. Michelle’s aiming for the sweaty pathos of Mary J Blige, and sometimes, as on Sometimes and Damn, she comes close.

What she’s missing is restraint. Just as she has no filter on the show, she ignores boundaries here, too, whether it’s the amusing and determined sprinkling of foul language throughout the album, or a song like Pay My Bills, a gauche number about sex and money. And then there are the songs that sacrifice some elegance in favor of disarmingly straightforward confessionals like I Don’t Like Me, on which K. Michelle sings, “All that I can see is she’s prettier than me/ Damn I wish I had her body.” It’s not artful, but it is affecting.

The same is true of My Life, the album opener, which begins, like many of the best songs here, with urgent piano. It’s a catalog of mistreatment and dark pathways, and also her testament about besting them: “All my life I been struggling and stressing/ That’s why I come up in this bitch with aggression.” Fortunately she didn’t waste it all on a TV show.

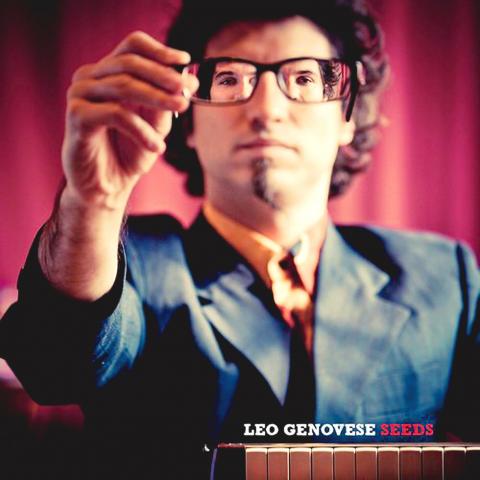

SEEDS

Leo Genovese

Montuno/Palmetto

Among the myriad ways that a youngish jazz musician can signal his or her readiness as a solo artist, a few might seem contradictory at a glance. Start with the shedding of historical emulation or the unabashed embrace of it: both good options, if handled well. Consider, too, an air of self-sufficiency versus a spirit of communion. Then there are the various expressions of leadership initiative, from take-charge to anything-goes.

Seeds is technically the third album by Leo Genovese, 34, an Argentine pianist, but it has the momentous urgency of a debut — and in its own way, meets every qualification noted above. Genovese, whose most prominent work up to now has been with the bassist and singer Esperanza Spalding, brings opposing forces into harmony. That the album bounces all over the place doesn’t feel like a problem for him.

Spalding appears on Seeds, but only on vocals, and on fewer than half of the tracks. The album’s core personnel, sometimes known as the Chromatic Gauchos, consists of another virtuoso peer, the saxophonist Dan Blake, and a pair of wise elders, the bassist John Lockwood and the drummer Bob Gullotti.

The album, which Genovese produced himself, was recorded almost entirely in a day, though it doesn’t sound like a rush job: its range and sprawl feel well considered. Several tunes here, especially Father of Spectralism and Let’s Get High, recall the enlightened swagger of Keith Jarrett’s so-called American quartet of the 1970s. Posterior Mode suggests McCoy Tyner’s late-1960s quartet with Joe Henderson. Letter From Wayne is a homage to Wayne Shorter, whose compositional signature has rarely been forged with such loving precision.

Genovese doesn’t get lost in these evocations, if only because he has such an untroubled sense of self. Playing acoustic and Fender Rhodes pianos, Hammond and Farfisa organs, and occasionally the melodica or Melodian — none of which he approaches as a lark — he exudes a busy composure. And by refusing to privilege one historical style over another, he strengthens his claim as a polyglot. The only cover is a song by the Argentine folk hero Atahualpa Yupanqui, offered as a solo piano hymn.

Another piece that incorporates Latin American folkloric elements is Portuguese Mirror, with lyrics by Spalding, and a guest turn by the Brazilian guitarist Ricardo Vogt. It seems a likely highlight of Genovese’s concert Wednesday at Subculture in NoHo, which will feature those collaborators as well as JP Jofre on bandoneon and Brian Landrus on bass saxophone. Whatever Seeds represents, we clearly haven’t heard the end of it.

Wooden houses wedged between concrete, crumbling brick facades with roofs gaping to the sky, and tiled art deco buildings down narrow alleyways: Taichung Central District’s (中區) aging architecture reveals both the allure and reality of the old downtown. From Indigenous settlement to capital under Qing Dynasty rule through to Japanese colonization, Taichung’s Central District holds a long and layered history. The bygone beauty of its streets once earned it the nickname “Little Kyoto.” Since the late eighties, however, the shifting of economic and government centers westward signaled a gradual decline in the area’s evolving fortunes. With the regeneration of the once

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

In February of this year the Taipei Times reported on the visit of Lienchiang County Commissioner Wang Chung-ming (王忠銘) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a delegation to a lantern festival in Fuzhou’s Mawei District in Fujian Province. “Today, Mawei and Matsu jointly marked the lantern festival,” Wang was quoted as saying, adding that both sides “being of one people,” is a cause for joy. Wang was passing around a common claim of officials of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the PRC’s allies and supporters in Taiwan — KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party — and elsewhere: Taiwan and

Perched on Thailand’s border with Myanmar, Arunothai is a dusty crossroads town, a nowheresville that could be the setting of some Southeast Asian spaghetti Western. Its main street is the final, dead-end section of the two-lane highway from Chiang Mai, Thailand’s second largest city 120kms south, and the heart of the kingdom’s mountainous north. At the town boundary, a Chinese-style arch capped with dragons also bears Thai script declaring fealty to Bangkok’s royal family: “Long live the King!” Further on, Chinese lanterns line the main street, and on the hillsides, courtyard homes sit among warrens of narrow, winding alleyways and