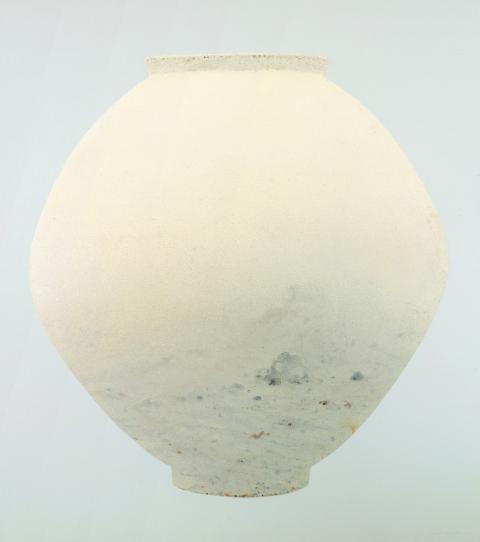

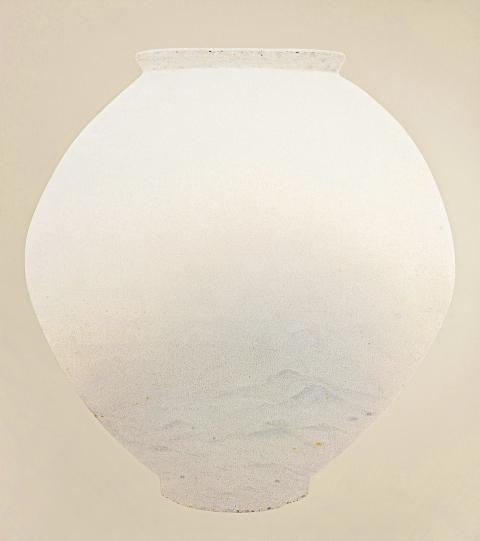

Over the past seven years, South Korean painter Choi Young Wook has consistently adopted the moon jar — a porcelain vessel in use during Korea’s late Joseon dynasty (1392-1910) — as the principal subject of his paintings, of which 22 are currently on display in Karma (緣). Choi perceives in the moon jar a pastoral aesthetic of common people. Weathering the course of history, caressed by human hands, bathed by water and rubbed by cloth for many years, the surface of these white porcelain jars change, acquiring scratches, and the “whiteness” of its exterior takes on a completely different quality. Permeated with the scars of life, the cracked glaze on the exterior of the moon jar often increases in the complexity of its fractured patterns, yielding an intermingling of the new with the old. Choi extends the moon jar’s many minute changes wrought by time to signify the universal life memories that humanity collectively shares. The cracked patterns of the glaze thus becomes a symbol of the mutual connections of fate, which he encompasses under the word karma. Here, metaphorically transformed by the artist, the white moon jars become vessels of life.

■ Art Issue Projects (藝術計劃), 32, Ln 407, Tiding Blvd Sec 2, Taipei City (台北市堤頂大道二段407巷32號), tel: (02) 2659-7737. Open daily from 11am to 6pm. Closed Mondays

■ Until Feb. 3

Photo courtesy of Art Issue Projects

Photo courtesy of Art Issue Projects

Photo courtesy of Art Issue Projects

Photo courtesy of Art Issue Projects

Photo courtesy of Art Issue Projects

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Toward the outside edge of Taichung City, in Wufeng District (霧峰去), sits a sprawling collection of single-story buildings with tiled roofs belonging to the Wufeng Lin (霧峰林家) family, who rose to prominence through success in military, commercial, and artistic endeavors in the 19th century. Most of these buildings have brick walls and tiled roofs in the traditional reddish-brown color, but in the middle is one incongruous property with bright white walls and a black tiled roof: Yipu Garden (頤圃). Purists may scoff at the Japanese-style exterior and its radical departure from the Fujianese architectural style of the surrounding buildings. However, the property