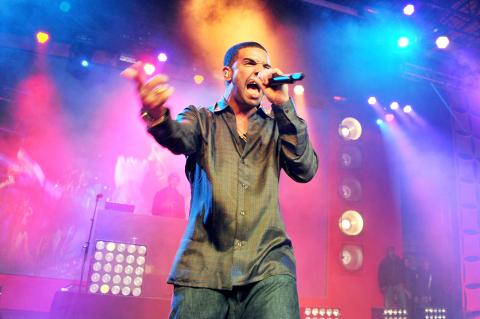

On a sunny Tuesday afternoon in southeast London, many of the 18,000 people who have paid to see Drake play the biggest concert of his career are already starting to converge on the O2 arena. It’s hours before showtime, but just knowing that the 25-year-old Canadian R ’n’ B singer-rapper is in the vicinity means the atmosphere is buzzing among the mixed throng of suburbanites and hipsters, some of whom have the acronym YOLO (it stands for You Only Live Once, from his song The Motto) tattooed on their bodies. Although how many of the devoted have it inked inside their mouths, as Drake will later explain is becoming increasingly popular in the US, is hard to gauge. One wonders how quickly the hip froideur would melt if Drake’s fans could see him backstage. In a large, empty room inside the arena, he is removing his gray tracksuit bottoms. It occurs that it might make sense, watching as he contemplates a marginally nattier pair of black trousers, to tweet this image of this “hashtag rapper” — as detractors, including his peer Ludacris, have called him — across the world.

Aubrey Drake Graham probably wouldn’t mind, either. This is someone who is happy to reveal all in his music, using it as therapy to talk about everything from the divorce of his parents and his grandmother’s illness to the bewilderment, loneliness and despair that result from being a jet-setting superstar multimillionaire. In fact, it’s his tendency to make being a jet-setting superstar multimillionaire seem like the most sorrowful, isolating existence on earth that has earned him many detractors.

Does he do so few interviews because much of what he has to say is in his songs? “Yeah,” he says. “It’s hard for me not to tell the truth when you ask me.”

Photo: AFP

Sometimes, he says, his honesty backfires, and a publication will use his candor against him. Recently he stormed out of an interview with Vibe magazine. “I didn’t like the way I was treated,” he says. “They ran this story about how I’m the most bitter guy, and my life is in turmoil. And I’m, like, a very happy 25-year-old kid living an amazing life. They tried to put a damper on my character, I guess because I didn’t play according to their rules.”

It is none the less this very quality — this sense of misery — that marks him out. Hip-hop has produced many characters — from Public Enemy’s radical militant and NWA’s police-dissing gangsta to 2Pac’s thug savant or Jay-Z’s uber hustler — but the wistful narcissist is a new paradigm for rap. To what extent is this really Drake, or a persona just as calculated as Marshall Mathers’ Slim Shady? “I don’t really have a gimmick or a ‘thing,’” he says. “I’m one of the few artists who gets to be himself every day.”

Ribbed for wearing sweaters and lacking, with his middle-class background (his African American musician father and Jewish Canadian teacher mother divorced when he was five, but he was brought up in Toronto’s affluent Forest Hill area), any ghetto credentials, Drake’s is an exaggerated, super-normality. “I don’t have to wake up in the morning and remember to act like this or talk like that,” he says. “I just have to be me. And people like that.”

Drake is every average dreamy boy incarnate, only with him the doubts and confusions of young adulthood are magnified because of his success and wealth. He recalls how, not long ago, he had an image of an LA mansion as his computer’s homepage. It was way out of reach even for a rising actor (he starred in Canada’s teen drama Degrassi) like him. “It was priced beyond my comprehension,” he says, then pauses. “Five weeks ago I bought it.”

No wonder some of his songs, such as the brilliant The Resistance from 2010’s Thank Me Later, find him unraveling fast. I ask him whether he’s the Morrissey of rap, but his music is far more complex than that. He wouldn’t say anything as black-and-white as Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now. Heaven knows I’m conflicted about my newfound status now, perhaps. “I let other people put tags on me,” he laughs, coming on like an irate indie fan, “otherwise they’ll be like, ‘Don’t ever mention your name in the same sentence as Morrissey!’” He’s quite the contradiction, is Drake. He can be maudlin one minute, self-aggrandizing the next. On the track Lord Knows he stakes a claim for himself as the rap Jimi Hendrix or Bob Marley.

“I didn’t really say I was the rap Hendrix or Marley, I said I was the descendant,” he corrects, smiling at the tenuous distinction. “Because I feel like that’s what I want to be for this generation: iconic. That’s the purpose I want to serve on this earth. I want my words to be remembered in 10, 15 years.” Hubris or not, he’s hardly alone in his mighty estimation. The New York Times dubbed him “hip-hop’s current center of gravity.” Encouraged by Kanye West’s 2008 album 808s and Heartbreak, his records, unimpeachably perfect in their pristine woe as he raises tortured self-regard to new heights, have seen a host of soundalikes appear in his wake. These include his Canadian protege the Weeknd’s tremulous angst, the exquisite “cloud rap” of Main Attrakionz, Clams Casino’s foggy productions and A$AP Rocky’s psychedelically ethereal melodies, which evince a love, shared by Drake, of Houston’s funereally slow “chopped and screwed” music. Even Tyler, the Creator’s mordant confessionals seem to orbit the same musical universe.

Drawing on hip-hop, chillwave, dubstep, downtempo electronica and R ’n’ B, Drake’s is the sound of now. He makes musical connections, and he’s super-connected, calling on everyone from Kanye and Nicki Minaj (who he once pretended to marry on Twitter) to James Blake and the xx to work with him. Of course, not everyone loves Drake. There are those detractors.

“I can’t lie to you,” he deadpans, “I read what they have to say and it’s ... character-building.” He used to find it mortally wounding. “There have been times when a negative comment about me would be the be all and end all, and I’d wonder, ‘Why do you hate me so much? Why would you tell me that you want to kill my mom or see me dead?’”

It’s a fair question, one that Drake has grown accustomed to asking. “It’s scary for me to say this on record,” he says, “but artists are only human, and we seek validation like everyone else. You just have to come to the conclusion that it’s OK, there are going to be people who like you and people who don’t. Luckily there are millions of people who love me and a few who don’t.”

This doesn’t sound like arrogance, just a fact about someone who has sold records to, well, millions. “No one ever says anything to me in person,” he adds. “I mean, I’ve had it happen to me before but it’s just silly, like, ‘Oh Drake, you’re a pussy!’ and then they drive off really fast. But I get it, man. It’s being young. It’s funny. If I wasn’t in this position, would I do dumb shit? Maybe.”

There’s a line in Drake’s notorious Marvin’s Room — “I’ve had sex four times this week, I’ll explain/Having a hard time adjusting to fame” — that is, for some, too much to bear: not only is he meeting all these hot models, he’s not even enjoying it. Can he see why people might be annoyed?

“It’s a valid stance, and I get it,” he says, explaining that it’s just part and parcel of his honesty. “There are people who really hate me and everything I stand for, like, ‘He’s so soft.’ But I’m not soft. I’m just not one of those people who’s closed off emotionally. I went through too much with my father and my mother, watching her go through her shit and be hurt ... I’ve seen too many people cry. Plus, I’ve had too many girls to ever feel uncomfortable about the man that I am.” How many? “I don’t know, man,” he says with a big smile. “I don’t want to get into numbers.” Far from an R ’n’ B loverman (there was also once some kind of romance with Rihanna), Drake undercuts his every boast with a melancholy that is eminently seductive. He even talks, in We’ll Be Fine, about suicide. “I say: ‘Never thoughts of suicide, I’m too alive,’” he points out, but even to mention the subject in a song, considering his wealth and fame, is strange. “Yeah, I know,” he says, “because you get artists in this position who go crazy and don’t know how to handle it. There are people who have killed themselves. There’s the overwhelming stress, how tired you are, the weight on your shoulders of going out here and giving 18,000 people entertainment ... It’s a lot of pressure.”

How do you handle it? Drugs?

“Have I sipped codeine before?” he asks for me. “Yeah, of course. Have I smoked weed? Yes. Do I drink wine? Yes. But do I do it excessively? No. I’m not a reckless guy. I do it all within moderation. I’m not into drugs.” He realizes what he has just said, and bursts out laughing, as do his crew. “I mean any outside the ones I just mentioned.”

He composes himself before heading off to entertain 18,000 Brits.

“Nah, that’s not me,” he decides. “I care too much about what I have. I’m not going to throw it away for that.”

May 11 to May 18 The original Taichung Railway Station was long thought to have been completely razed. Opening on May 15, 1905, the one-story wooden structure soon outgrew its purpose and was replaced in 1917 by a grandiose, Western-style station. During construction on the third-generation station in 2017, workers discovered the service pit for the original station’s locomotive depot. A year later, a small wooden building on site was determined by historians to be the first stationmaster’s office, built around 1908. With these findings, the Taichung Railway Station Cultural Park now boasts that it has

Wooden houses wedged between concrete, crumbling brick facades with roofs gaping to the sky, and tiled art deco buildings down narrow alleyways: Taichung Central District’s (中區) aging architecture reveals both the allure and reality of the old downtown. From Indigenous settlement to capital under Qing Dynasty rule through to Japanese colonization, Taichung’s Central District holds a long and layered history. The bygone beauty of its streets once earned it the nickname “Little Kyoto.” Since the late eighties, however, the shifting of economic and government centers westward signaled a gradual decline in the area’s evolving fortunes. With the regeneration of the once

The latest Formosa poll released at the end of last month shows confidence in President William Lai (賴清德) plunged 8.1 percent, while satisfaction with the Lai administration fared worse with a drop of 8.5 percent. Those lacking confidence in Lai jumped by 6 percent and dissatisfaction in his administration spiked up 6.7 percent. Confidence in Lai is still strong at 48.6 percent, compared to 43 percent lacking confidence — but this is his worst result overall since he took office. For the first time, dissatisfaction with his administration surpassed satisfaction, 47.3 to 47.1 percent. Though statistically a tie, for most

In February of this year the Taipei Times reported on the visit of Lienchiang County Commissioner Wang Chung-ming (王忠銘) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a delegation to a lantern festival in Fuzhou’s Mawei District in Fujian Province. “Today, Mawei and Matsu jointly marked the lantern festival,” Wang was quoted as saying, adding that both sides “being of one people,” is a cause for joy. Wang was passing around a common claim of officials of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the PRC’s allies and supporters in Taiwan — KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party — and elsewhere: Taiwan and