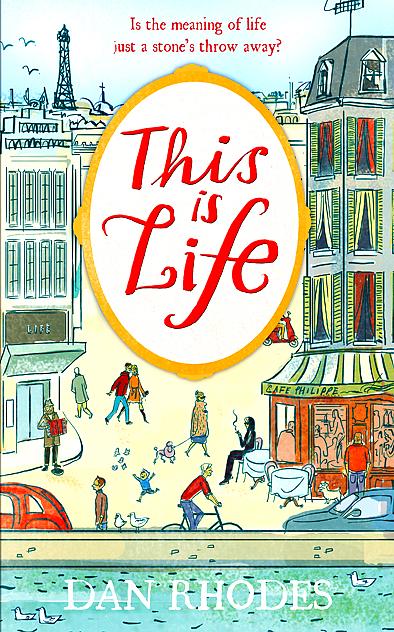

In the opening chapter of his new novel, Dan Rhodes describes a young student in Paris throwing a stone into the air which unfortunately lands on the face of a baby called Herbert (pronounced “Air-bear” in France). This leads to the convergence of many far-fetched stories.

This Is Life appears to mark a very deliberate change in the style and form of Rhodes’ fiction. For one thing, it is almost as long as the sum of all his previous novels: Timoleon Vieta Come Home, Gold, Little Hands Clapping and The Little White Car, which he wrote under the name Danuta de Rhodes. In one sense this change of tone and focus is similar to that between Michel Faber’s short, original and disturbing semi-science fiction novel Under the Skin and the well-crafted, obvious best seller The Crimson Petal and the White. Does this suggest that Rhodes is also about to move into the best-seller lists?

There is some evidence to suggest this may be in his mind. In one scene Sylvie, a girl with many jobs, sells an admirer a copy of her favorite novel Timoleon, Chien Fidele (a translation of Rhodes’s tragic version of Lassie Come Home). “I love the ending,” Sylvie says. “It’s not easy to read, but it says something that needs to be said. I don’t think I could ever really be friends with anyone who didn’t get this book.” And her admirer replies: “I love the ending too. I’m buying it to depress a friend of mine who’s been a bit too happy lately.” Both of them agree on the author’s brilliance and “how underappreciated he was.”

Over the past decade Rhodes’ fiction has grown darker and more nightmarish, but This Is Life is his farewell to tragedy. It is a happy book about love, from the author of the lacerating short story collection Don’t Tell Me the Truth About Love (the epigraph came from Iago’s speech inviting us to “Drown cats and blind puppies”). Is he now telling us the truth about love? Or has he become sentimental? It is remarkable indeed for characters in a Dan Rhodes novel to get to the point where “everything was as wonderful as they had known it would be.” So love is triumphant; and justice, too, predominates. Even baby “Air-bear,” when fortuitously reunited with his mother, loses his italics and regains the romantic dignity of his real name, Olivier.

Inevitably there are some dark notes. The boy who holds his breath for longer than a cormorant can stay under water subsides into an unending coma, and the sympathetic translator, who loves someone who does not love him, goes for solace into a monastery (he does find some comfort, not in the religion of the place, but from the fruit and vegetables he tends).

So what has happened to Rhodes? It is as if Samuel Beckett had suddenly come up with a glorious, high-spirited comedy. The desperate, idiosyncratic characters of his earlier macabre novels are not abandoned, but they are clothed now in a more traditional habit of storytelling that reveals how their craziness arises from understandable and even sometimes admirable origins. The author is generous and forgiving to them. When the art student accidentally shoots the baby she is looking after, Rhodes allows the bullet merely to graze the baby’s arm. I tremble to think what might have happened to this baby in his previous fiction.

The comedy is invigorated by some sharp political and artistic irony involving French President Sarkozy, Carla Bruni and even (at a distance) Lady Gaga. But grief and darkness are always near. They are most ominously present in the title of the novel, which refers to a theater presentation of daily routine and bodily functions called Life; this remorselessly shows the characters how much, each day, we leave behind with our feces and urine and sweat. The “something that needs to be said” in Rhodes’ previous novels is that sentimentality is a false medicine bringing little contentment, encouraging disappointment and provoking our vengeance. This novel cleverly avoids such dangerous medicine. It is a reminder of how strange ordinary life is and it challenges us to “adjust to the darkness.”

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the