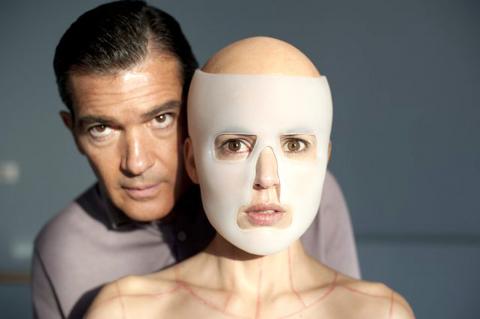

There’s an early decisive moment in Pedro Almodovar’s exhilarating film The Skin I Live In, when Robert Ledgard, a plastic surgeon and madman played with soul weariness by Antonio Banderas, gazes at the image of a woman on the wall of his bedroom. She’s bigger than life, this woman, and more beautiful. He calls her Vera (Elena Anaya), and she’s stretched out in the classic recumbent pose of the odalisque: that exotic Turkish harem dweller and Orientalist fantasy painted by the likes of Goya, Ingres and Manet, and given opulent new life and reverberant meaning by Almodovar, a master of his art.

In paintings of odalisques, the often naked women lie across the image like unwrapped gifts, exquisitely available to the men who paint them and to the patrons who value such female voluptuaries. There’s something different about Vera, though it’s initially difficult to pinpoint what. Ledgard lives in a mansion brightened with paintings of big nudes and blooms, and when you first see him looking at Vera, it’s as if he were viewing another canvas or a photo, or peering into a window. Yet this is no ordinary image; rather, it’s a surveillance video, and Vera has just tried to kill herself. Ledgard won’t stand for that and rushes in to save her, patching up a body that’s the centerpiece in an intoxicating, lush mystery.

There are several genres nimbly folded into The Skin I Live In, which might be described as an existential mystery, a melodramatic thriller, a medical horror film or just a polymorphous extravaganza. In other words, it’s an Almodovar movie with all the attendant gifts that implies: lapidary technique, calculated perversity, intelligent wit. There’s also beauty and spectacle, of course, especially as embodied by Vera, who usually wears a body stocking with gloves and booties, and knows exactly what she looks like. Watch how she watches Ledgard watching her, a relay of looks that evokes John Berger’s observation: “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” Were we born this way or made? Almodovar has his ideas, which he playfully explores with each labyrinthine turn.

Photo courtesy of Catchplay

The story is impossible — and weird, dark, funny and fractured, even jagged. It opens on a cityscape and the dateline “Toledo 2012” (as in Spain, not Ohio), the first indication that we’re not in Kansas anymore. It’s a shivery intimation of a futureworld, but it’s followed by a nod to Citizen Kane as the camera glides past a gate and into an isolated mansion. There Vera lives in a bright, locked room with a Spartan-modernist ambience, where she does little else except watch nature TV, practice yoga, scribble on the walls and create little busts inspired by the biomorphic forms of Louise Bourgeois. Ledgard calls her his patient, though she would rightly call herself his prisoner, as well as the object of his obsession.

How Vera got in that room and why are only two of the many mysteries in The Skin I Live In. Almodovar seeds the narrative with assorted teasing clues, quickly draping a shadow across half a face, for instance, a bifurcation that suggests both a divided self and a yin-yang symbol. Mostly, he plunges you straight into a story that moves, restlessly, at times imperceptibly, between the present and past. As in Vertigo (another of this film’s touchstones), the past and present exist in a loop, at least for a man obsessed. Eventually, the galvanizing points on that time continuum come into focus, including an accident that badly burned Ledgard’s wife, prompting his search for a new type of skin.

It takes time to get a handle on the story (and even then, your grip may not be secure), though it’s instantly clear that something is jumping beneath the surface here, threatening to burst forth. Vera’s plight and the temporal shifts help create an air of unease and barely controlled chaos, an unsettling vibe that becomes spooky when Ledgard puts on a white lab coat and begins doing strange things with blood. Almodovar doesn’t paint the screen red, at least not right away. Instead he daubs it on, the crimson easing in by way of the curtains Ledgard lectures in front of and in the droplets he perfectly places on glass plates. Later the blood will splash across a white bed in a frenzy of violence, an abstract expressionist splatter.

Photo courtesy of Catchplay

There are times in The Skin I Live In when it feels as if the whole thing will fly into pieces, as complication is piled onto complication, and new characters and intrigues are introduced amid horror, melodrama and slapstick. “You’re insane!” a colleague tells Ledgard, who doesn’t look terribly surprised by the news. Later, a rapist, Zeca (Roberto Alamo), in a tiger suit rings the doorbell, and one fateful night Ledgard’s daughter, Norma (Blanca Suarez), meets a young man, Vicente (Jan Cornet). Despite all these moving, spinning parts, Almodovar’s control remains virtuosic and the film hangs together completely, secured by Vera and Ledgard and a relationship that’s a Pandora’s box from which identity, gender, sex and desire spring.

Banderas and Anaya are excellent, though neither has been directed to seduce like some of the director’s past memorable characters. (A spikily human, funny Marisa Paredes, as Ledgard’s fanatically loyal housekeeper, Marilia, supplies plenty of warmth.) For good story reasons, Vera is largely opaque, while Ledgard remains at arm’s length: She is a question that he’s asked but at first can’t answer.

There’s a vital toughness, in particular, to Banderas, as this likable if often misused actor goes dark without compromising his character with softness or light. It’s a gutsy turn, and while your eyes are often, reasonably, on Anaya, it’s a pleasure to experience a performance from Banderas that peels away his persona and burrows under the skin.

Photo courtesy of Catchplay

Photo courtesy of Catchplay

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Aug. 25 to Aug. 31 Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household. In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized,

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

During the Metal Ages, prior to the arrival of the Dutch and Chinese, a great shift took place in indigenous material culture. Glass and agate beads, introduced after 400BC, completely replaced Taiwanese nephrite (jade) as the ornamental materials of choice, anthropologist Liu Jiun-Yu (劉俊昱) of the University of Washington wrote in a 2023 article. He added of the island’s modern indigenous peoples: “They are the descendants of prehistoric Formosans but have no nephrite-using cultures.” Moderns squint at that dynamic era of trade and cultural change through the mutually supporting lenses of later settler-colonialism and imperial power, which treated the indigenous as