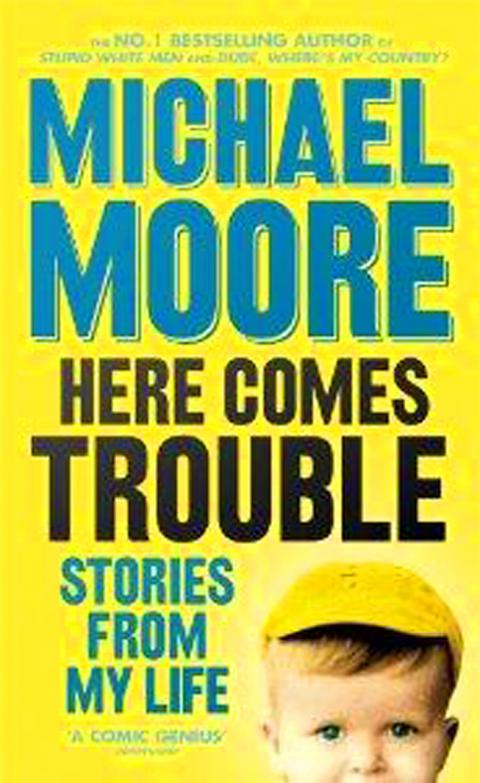

Michael Moore’s Here Comes Trouble has done more than give me a great deal of pleasure. It has reminded me, in a manner that’s both witty and perspicacious, of the kind of life I all too often wish I’d been brave enough to live myself.

A critic reviewing the book in the Guardian wrote that it resembled a saint’s life — how its subject was miraculously conceived, exhibited a precocious talent to the astonishment of his elders, and so on. This hostile description, however, omits one huge fact: Michael Moore is extremely funny. Not only are saints’ lives rarely funny, the humor also protects Moore from the self-promotion the critic was implicitly accusing him of.

Moore calls this book “short stories based on events that took place in the early years of my life.” The events narrated are clearly true, and the “short stories” line is merely a formula to account for the quotations re-created in direct speech, a device many writers resort to in the interests of freshness and comic effect.

I’m a great fan of Moore because his values are values I share, and because his disarming frankness is something I instinctively admire. It no doubt takes a country like the US, where the behavior of the political right is so outrageous and causes so much suffering, to produce a phenomenon like him. He’s a real David, nonetheless, who routinely stands up and confronts some of the biggest Goliaths on his home stage.

He’s also valuable because he speaks a satiric language that ordinary people can understand. These are often people who before Moore came along were all too willing to swallow the soft-spoken lies put out by the big corporations — even more frequently the targets of Moore’s exposures than US politicians. Early on he resolves to “never, ever believe at face value anything a government or corporation tells you.”

The essence of Moore’s effectiveness is that he’s both a social activist and a comedian. There are many activists, and there are many comedians, but when the two skills combine the effect is stupendous. This is especially apparent in print, where Moore is much funnier than he manages to be in his films.

What this fine book also demonstrates is that men like Moore have often been battling away for a long time before they come to the attention of the general public. Thus we see that Moore showed his true colors early, giving an inflammatory and prize-winning speech at a summer camp for students when he was only 17.

A prize had been offered by a society called the Elks for the best address on Abraham Lincoln. But Moore remembered that these same Elks ran a golf club near his hometown that his father had refused to join because it was for “Caucasians only.” How hypocritical for such people to run a competition for speeches on, of all people, Lincoln! So protested the young Moore, to the cheers of his fellow students, and with the chief Elk sitting red-faced behind him on the platform.

Another message of this book is that a few people can often cause a stir, both in politics and in life in general. Reading this, I was reminded of a friend who, in the UK in the 1970s, teamed up with a colleague and started an organization opposing the dumping of nuclear waste at sea. Only months after their group had been in existence, the two of them noticed that their car was being followed as they drove up to London for a rally on nuclear issues in Hyde Park.

Moore would appreciate that. Another story he’d like was one told me in those days by someone working for the immigration authorities at London’s Heathrow Airport. New arrivals were taken away for questioning, he said, if certain key words appeared in their reasons for wanting to enter the country. “Like what?” I asked. “Peace,” he replied.

Other issues the young Moore takes up are the perfidy in matters of employment of many large corporations (his hometown is Flint, Michigan, where General Motors first started), the cruelty of anti-abortion laws, the often lethal effects of anti-gay sentiment back in the 1960s, the pervasiveness of American racism, and the reactionary implications of fundamentalist Christianity. None of these phenomena have, needless to say, entirely disappeared.

Moore seems to me to be a sort of old-fashioned patriot and moralist. He believes in American jobs for American workers, in the original charitable teachings of Jesus Christ rather than the anti-sex views of most modern churches, and in the wrongness of war.

He’s also a big supporter of unions. In his home street when he was a boy, he reports, everyone belonged to a union. “This meant they worked a 40-hour week, had the entire weekend off (plus two to four weeks’ paid vacation in the summer), comprehensive medical benefits, and job security. In return for all that, the country became the most productive in the world.”

But by the era of former US president Ronald Reagan, as a colleague remarks to Moore, there was a shift taking place in the US: Those with money wanted to turn the clock back to a time when everybody else had to “beg for crumbs.”

It’s immensely pleasing that, in a nation characterized by high levels of Christian observance but also very high levels of military expenditure, someone who points out simple contradictions, emphasizes kindness and good nature, and champions the little man against the big corporations and the political parties can be so successful.

Several of Moore’s film documentaries have, after all, broken box-office records, and one can only hope that this new book will sell in large numbers, and influence many loyal Americans, while they laugh, to embrace once again the altruistic principles on which their great country was founded.

Wooden houses wedged between concrete, crumbling brick facades with roofs gaping to the sky, and tiled art deco buildings down narrow alleyways: Taichung Central District’s (中區) aging architecture reveals both the allure and reality of the old downtown. From Indigenous settlement to capital under Qing Dynasty rule through to Japanese colonization, Taichung’s Central District holds a long and layered history. The bygone beauty of its streets once earned it the nickname “Little Kyoto.” Since the late eighties, however, the shifting of economic and government centers westward signaled a gradual decline in the area’s evolving fortunes. With the regeneration of the once

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook

Perched on Thailand’s border with Myanmar, Arunothai is a dusty crossroads town, a nowheresville that could be the setting of some Southeast Asian spaghetti Western. Its main street is the final, dead-end section of the two-lane highway from Chiang Mai, Thailand’s second largest city 120kms south, and the heart of the kingdom’s mountainous north. At the town boundary, a Chinese-style arch capped with dragons also bears Thai script declaring fealty to Bangkok’s royal family: “Long live the King!” Further on, Chinese lanterns line the main street, and on the hillsides, courtyard homes sit among warrens of narrow, winding alleyways and