He had “a sun in his head and a thunderstorm in his heart”: These words used to describe French painter Eugene Delacroix were memorized by Vincent van Gogh and could just as easily been applied to Van Gogh himself.

From his turbulent emotional life, filled with loneliness and despair, there sprang — in a single, incandescent decade — a profusion of dazzling, vibrant paintings that fulfilled his ambition to create art that might provide consolation for the bereaved, redemption for the desperate. Images that would “say something comforting as music is comforting — something of the eternal” phosphorescent stars cartwheeling through a nighttime sky in the yellow moonlight; a clutch of radiant irises blooming in a lush garden lit by the Mediterranean sun; a flock of crows winging their way across a golden expanse of wheat fields under a stormy sky.

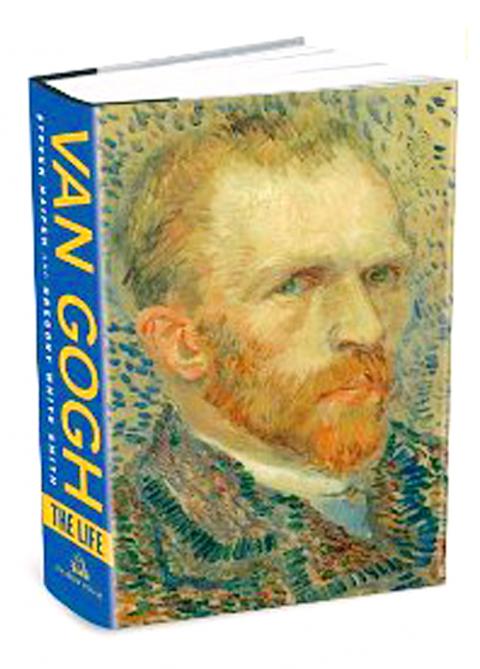

In their magisterial new biography, Van Gogh: The Life, Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith provide a guided tour through the personal world and the work of that Dutch painter, shining a bright light on the evolution of his art while articulating what is sure to be a controversial theory of his death at the age of 37.

Whereas suicide by gun has long since become part of the myth of the tortured artist that cloaks Van Gogh, Naifeh and Smith note that there are issues with that hypothesis — like the angle of the shot, the disappearance of the gun and other evidence, and the long hike that the wounded Van Gogh would have had to make to return to his lodgings. Instead they propose an intriguing alternate theory, rumors of which were first heard by art historian John Rewald in the 1930s during a visit to Auvers, the small French town where Van Gogh died.

As Naifeh and Smith tell it, a rowdy teenager named Rene Secretan, who liked to dress up in a cowboy costume he’d bought after seeing Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, was probably the source of the gun (sold or lent to him by the local innkeeper). Secretan and his friends used to bully the eccentric Van Gogh, and the authors suggest that there was some sort of encounter between the painter and the boys on the day of the shooting.

“Once the gun in Rene’s rucksack was produced,” they write, “anything could have happened — intentional or accidental — between a reckless teenager with fantasies of the Wild West, an inebriated artist who knew nothing about guns, and an antiquated pistol with a tendency to malfunction.”

The deeply unhappy Van Gogh, the authors argue not altogether convincingly, “welcomed death,” and Secretan may have provided him “the escape that he longed for but was unable or unwilling to bring upon himself.’”

There is no hard evidence for this theory, and it is laid out, discreetly, in an appendix to this biography. Which is as it should be, since the real reason to read this book has nothing to do with speculation about Van Gogh’s death but with the voluminous chronicle it provides of his life and art, and the alchemy between them. The overall portrait of Van Gogh that emerges from this book will be familiar to readers of earlier biographies — most notably David Sweetman’s succinct 1990 study — but it is fleshed out with details as myriad as the brushstrokes in one of his late paintings.

In writing this book (and providing a companion Web site with notes), the authors drew heavily on archival material and scholarship at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and most notably from a new edition of Van Gogh’s letters, which was 15 years in the making and published in 2009. Like earlier biographers, their ability to persuasively depict Van Gogh’s inner life is hugely dependent on these remarkable letters — letters that not only chronicle his manic ups and downs, his creative process and his complex relationship with his beloved brother Theo, but that also attest to his immense literary gifts and his iron-willed determination to learn and grow as an artist.

Drawing upon these letters and Van Gogh’s drawings and paintings, Naifeh and Smith provide a minutely annotated map of the intellectual underpinnings of his philosophy and art. Although he could be erratic and difficult, and although he suffered breakdowns and depressions, Van Gogh was far from the madman of myth. His sensibility and art were shaped by his avid reading of writers like Dickens, Shakespeare, George Eliot and Zola, just as his admiration for a succession of painters and the ever-growing museum of images in his head informed his evolving vision and techniques as a painter.

Van Gogh’s early, somber paintings of peasants were inspired, partly, by Millet, and aspired, the authors say, “to celebrate not just the peasants’ oneness with nature” but also “their stolid resignation in the face of crushing labor.” His later paintings with an electric palette owed a debt to the Impressionists, whom Theo had urged on him for years in the hopes that Vincent would paint more landscapes and use more color to produce more saleable canvases.

Van Gogh would also learn from the pointillism of Seurat, the primitive simplicity of Japanese prints, the Symbolists’ embrace of dreamlike imagery. Smith and Naifeh nimbly trace Van Gogh’s peregrinations, and they evoke the intense atmosphere of creative ferment in Paris during the 1880s. They dissect how Van Gogh’s restless, obsessive and highly contrarian intellect hungrily assimilated and transformed disparate philosophies, iconography, even brushwork, and how he moved from explorations of the play of light on surfaces to more intense excavations of his own psyche, from simple descriptions of reality toward a more expressionistic style that would remake the world as a mirror of his own “fanatic heart.”

Along the way we are given insights into how Van Gogh’s gymnastic use of color reflected his ever-changing moods: the piercing yellow of a vase of sunflowers saluting the sun that suffused his life in Arles; the serenity of a new palette of violet, lavender and lilac that crept into his paintings while he was at the Asylum of St Paul in St Remy; the stormy blues and ominous clouds, suggesting a threatening view of nature, conjured on the late canvas Wheat Field With Crows.

What Naifeh and Smith capture so powerfully is Van Gogh’s extraordinary will to learn, to persevere against the odds, to keep painting when early teachers disparaged his work, when a natural facility seemed to elude him, when his canvases failed to sell. There was a similar tenacity in his heartbreaking efforts to fill the emotional void in his life: ostracized by his bourgeois family, which regarded him as an unstable rebel; stymied in his efforts to pursue his religious impulses and become a preacher; rejected or manipulated by the women he longed for; shunned and mocked by neighbors as crazy; undermined by a competitive Paul Gauguin, with whom he had hoped to forge an artistic fraternity.

The one sustaining bond in Van Gogh’s life was with Theo, an art dealer, who provided emotional, creative and financial support. The authors of this book convey the love and exasperation that Theo felt for his needy, demanding brother and how fearful Vincent was of losing Theo’s devotion.

Vincent Van Gogh’s lifelong yearning for emotional connection, of course, would finally, and most lastingly, be realized in his art. “What I draw, I see clearly,” he wrote as he was beginning to find his vocation.

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the