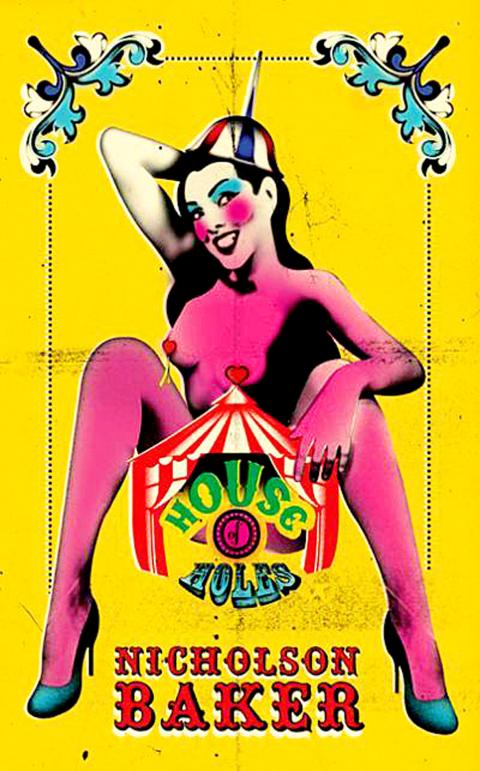

Here is a highly abbreviated chapter from Nicholson Baker’s full-throttle pornographic new novel, House of Holes:

“We’re professionals. I know it may seem a little strange to you that we don’t have pants on.”

“I thought about you yesterday. I did rude things to an orange.”

“This is pleasant.”

“Whooo!”

“Ooh boy.”

“Ohhhhhrrrrr.”

“Bye-bye.”

“Did you take off your sponge gloves?”

There’s more, of course. But you aren’t supposed to eye it in a newspaper. You’re supposed to be teased into reading the full, unexpurgated House of Holes by even the tiniest peek at its fantasies and taste of its lingo. “Newspaper” is the only word in this paragraph that Baker, 54, now staking his claim to the title of World’s Oldest Teenage Boy, couldn’t give a smirky spin.

Among the unusual eroticized terms that turn up in House of Holes are “united parcel,” “chickenshack,” “address book,” “subway improvement project,” “the fondling fathers” and “cold Snapple in my condo.” Malcolm Gladwell could either sue or thank Baker, depending on how he feels about seeing his name used as a ha-ha synonym for a body part. However much fun he has toying with innuendoes, Baker finds lots of time for the Anglo-Saxon standbys too.

With a vocabulary like that, House of Holes comes with built-in hyperbole. It all but demands to be called the dirtiest book ever to emanate from an author who already has Vox and The Fermata on his curriculum vitae (not to mention Double Fold, a manifesto aimed at libraries, which won a National Book Critics Circle award for nonfiction). But Baker’s earlier sex books veered into pervier territory, making House of Holes pretty innocent by comparison. This new book seems a deliberate course correction after The Fermata, about a man with a yen for secretly undressing women and a magical ability to make time stand still. The behavior that he called “chronanistic” gave more than one kind of pause.

No such kinks marginalize House of Holes. It describes a happy, friendly, doofy, incredibly polite (“May I?”) equal-opportunity playland where anybody can seemingly fulfill any sexual daydream, ideally while talking about it as graphically as possible. Actually there are limits: Baker has a well-hidden prim streak, and he sticks to cheery little vignettes in which everybody gets hot but nobody gets hurt.

Because House of Holes is sheer fantasy, it’s possible for a guy named Dave to lose an arm without suffering any real damage. He’ll get it back eventually. And while the arm is on the loose, it will make friends with a woman named Shandee. “Is that somebody’s arm you’ve got tucked away in your lap?” she is asked.

There’s no particular plot to House of Holes. People get whooshed through various portals and wind up at a friendly, porn-filled, oddly bureaucratic resort. The place is run by a woman named Lila, and she evaluates the needs of each new guest, sometimes even using a calculator to do so. Lila does quite the entrance interview. (“Can I kiss it a little, hon? To get a better diagnosis?”)

When one man describes a dream that involves slightly more than 4,000 people — and, now that he thinks about it, really ought to include every woman in the world — Lila is the voice of reason. “That’s not really our style,” she tells him, “but I like your ambition.” Another guest with over-the-top ideas involving a centaur is flatly told, “You’ve been watching cable.”

Since a lot of these close encounters end in ecstatic moaning, there’s a certain sameness here. And House of Holes is better when it’s crudely funny than when it’s just plain crude.

House of Holes is no study in subtlety. That may seem like an irrelevant complaint, but Baker has a readership that has followed him into gravitas (Human Smoke), hubris (U and I) and minutiae (The Mezzanine), counting on him for scrutiny so close it approaches the molecular and a milquetoast manner that’s as ingratiating as it is batty. Wherever this narrative voice wanders, it is always his own.

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

Enter the Dragon 13 will bring Taiwan’s first taste of Dirty Boxing Sunday at Taipei Gymnasium, one highlight of a mixed-rules card blending new formats with traditional MMA. The undercard starts at 10:30am, with the main card beginning at 4pm. Tickets are NT$1,200. Dirty Boxing is a US-born ruleset popularized by fighters Mike Perry and Jon Jones as an alternative to boxing. The format has gained traction overseas, with its inaugural championship streamed free to millions on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Taiwan’s version allows punches and elbows with clinch striking, but bans kicks, knees and takedowns. The rules are stricter than the

“Far from being a rock or island … it turns out that the best metaphor to describe the human body is ‘sponge.’ We’re permeable,” write Rick Smith and Bruce Lourie in their book Slow Death By Rubber Duck: The Secret Danger of Everyday Things. While the permeability of our cells is key to being alive, it also means we absorb more potentially harmful substances than we realize. Studies have found a number of chemical residues in human breast milk, urine and water systems. Many of them are endocrine disruptors, which can interfere with the body’s natural hormones. “They can mimic, block

Nearly three decades of archaeological finds in Gaza were hurriedly evacuated Thursday from a Gaza City building threatened by an Israeli strike, said an official in charge of the antiquities. “This was a high-risk operation, carried out in an extremely dangerous context for everyone involved — a real last-minute rescue,” said Olivier Poquillon, director of the French Biblical and Archaeological School of Jerusalem (EBAF), whose storehouse housed the relics. On Wednesday morning, Israeli authorities ordered EBAF — one of the oldest academic institutions in the region — to evacuate its archaeological storehouse located on the ground floor of a residential tower in