You don’t have to be rich to collect art. All that’s required is a lot of passion and a willingness to work a second job to earn some extra money. This is the central premise of Invisibleness is Visibleness: International Contemporary Art Collection of a Salaryman — Daisuke Miyatsu, currently on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei (MOCA, Taipei).

Miyatsu, born in 1963, has become the stuff of legend in Japan’s art circles since the first exhibit of his collection, Why Not Live for Art?, was showcased at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery in 2004. Known for his keen collector’s eye and compulsive research when deciding which works to buy, the salaryman is so obsessed with art (which MOCA, Taipei calls an “addiction”) that he’s had artists ink tattoos onto his body.

He commissioned 2002 Marcel Duchamp Prize winner Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster to design his “dream house,” a “work in progress” modernist structure located in a Tokyo suburb. It features a bathroom and wallpaper by Shimabuku, sliding screen doors by Yoshitomo Nara and a full-length mirror by Yayoi Kusama, among other objects, fixtures and designs by high-profile artists. The exhibit devotes a section to this house, complete with a model.

Photo Courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo

“He’s a good student of art. He studied English for the express purpose of talking to artists overseas. During the weekends he goes to several exhibits and art openings because this is the time that you can meet artists and establish relationships with them — understand who they are and if they are in it for the long haul,” said Natasha Lo (羅健毓), the exhibit’s curator.

Lo added that Miyatsu “doesn’t go to art fairs — like Art Basel or the Venice Biennale — because his thinking is, ‘Why spend money on a plane ticket when the money can be used to buy a work of art?’” It should be noted that Miyatsu does go to international art fairs, but only when he’s invited to give a speech (as he will at the forthcoming Art Taipei, on Aug. 27 from 2:30pm to 4:30pm).

The MOCA, Taipei exhibit comprises 61 works by 51 artists from the 300-plus pieces in the collection amassed by Miyatsu, who started buying artwork in 1994 when he was 30 years old. Over the past 17 years, he’s spent NT$10 million (US$350,000) on art.

Photo Courtesy of Project Fulfill Art Space

While Miyatsu’s collecting habits may deserve an entry in the weighty Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (“compulsive art collecting disorder,” say), there is no doubt that he is a boon to galleries and artists.

So, before going any further, let’s address the tricky business of a public art museum hosting an exhibit for a private collector — an enterprise that will probably boost the collection’s value.

As a March article in the New York Times by Judith H. Dobrzynski pointed out, single-collector exhibits raise several issues that pose a threat to their legitimacy.

“When the collectors are trustees or provide financing for an exhibition, it looks as if the museum is selling out to vanity shows or renting its galleries. If museums show a collection without the promise of a gift, they are seen as endorsing the art and elevating its value. If museums display art that comes with a gift, they seem — unless it is the entire collection — to be using a questionable fund-raising tool at best, or exacting a quid pro quo at worst. The question always arises as to who is making the curatorial decisions, museum or collector? And when collectors sell art after the exhibition, the museum looks as if it has been used.”

The exhibit largely avoids such criticism. MOCA, Taipei doesn’t have a permanent collection and is funded partly by the Taipei City Government and partly by the sale of museum tickets, catalogues and souvenirs. Critics, however, could point to the fact that the show’s curator operates Agora Art Project x Space (藝譔堂), a gallery that represents one artist in the show. Perhaps a bigger criticism revolves around the museum’s relinquishing of curatorial control to Lo and Miyatsu. Two things here: Are the curators transparent about these decisions and is the show worthwhile? For this reviewer, a resounding yes on both counts.

There seems to be agreement among art professionals (artists, curators and educators) that bureaucrats interfere too much in the decision-making process at public art institutions. The thinking goes that government officials in positions of power too often believe that these publicly funded institutions are their fiefdoms. There has recently been a vocal backlash over this issue, as the recent resignation of Taipei City Cultural Affairs Commissioner Hsieh Hsiao-yun (謝小醞) over controversies at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM) illustrates.

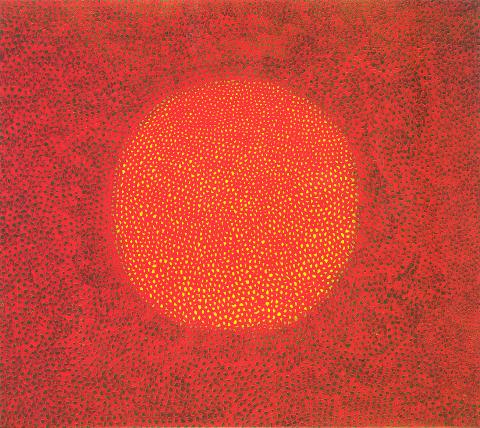

In any event, Invisibleness is Visibleness deserves to be seen. It begins with a room-cum-shrine devoted to Miyatsu’s beloved Yayoi Kusama, and includes Infinity Dots, his first collected work (which, according to the collector’s chronology, was in 1994), as well as Infinity Net, his most valuable. (Lo said Miyatsu couldn’t afford to buy the latter work outright, so he arranged a two-year payment plan with the gallery.)

There is also a small section on conceptual art, featuring a 1972 visual installation by Vito Acconci (Untitled Project for Pier 17) and a 1996 sculpture by Jan Fabre (Krijgers Rozenkrans Warrior’s Rosary).

But the exhibit stands out mostly for its display of new media art, particularly by emerging video artists. Often this medium appears an amateur mix of music video and ad kitsch, and there are some videos here that are like that. But Takagi Masakatsu’s Tidal is a luscious and ethereal video of girls and women moving fluidly through space, celebrating the pleasures of youth, beauty and romance. Miyatsu certainly has a good eye.

However, as is often the case with exhibits at MOCA, Taipei, there is too much of a good thing. While watching Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s sumptuous video My Mother’s Garden, I was constantly distracted by Tadasu Takamine’s video God Bless America, a humorous, if screechy (the title song is sung throughout), take on American cultural imperialism, in the middle distance and the din of squealing pigs in Wu Chang-jung’s (吳長蓉) kaleidoscopic Documentary IV — Little Mince Cloth beyond. The 11 videos crammed into the second floor audiovisual space didn’t make for the best viewing experience.

Regardless, Invisibleness is Visibleness serves as a powerful argument to allow single-collector exhibits into the museum space — though with caveats — and proves its thesis that collecting art isn’t as exclusive a pastime as is sometimes thought.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Toward the outside edge of Taichung City, in Wufeng District (霧峰去), sits a sprawling collection of single-story buildings with tiled roofs belonging to the Wufeng Lin (霧峰林家) family, who rose to prominence through success in military, commercial, and artistic endeavors in the 19th century. Most of these buildings have brick walls and tiled roofs in the traditional reddish-brown color, but in the middle is one incongruous property with bright white walls and a black tiled roof: Yipu Garden (頤圃). Purists may scoff at the Japanese-style exterior and its radical departure from the Fujianese architectural style of the surrounding buildings. However, the property