These last weeks, not for the first time, I’ve been despairing of the modern world, especially the US world. Wars are being waged in Iraq and Afghanistan using drones “piloted” by personnel sitting at computers in places like Pennsylvania. Far-off people are killed, possibly sometimes unintentionally, while the young are chattering away on Twitter, Facebook and the rest about — if my friends are typical — utterly trivial subjects. Few connect Washington’s debt crisis with the fact that by some calculations, the US spends more on its military than all the other nations on Earth put together.

But who’s protesting? Where are are the mass rallies that effectively put an end to the US adventure in Vietnam decades ago? The young are also heavily into computer games that almost invariably center on killing and were pioneered with the assistance of the Pentagon. And, to cap it all, these drone-operators are using technologies closely related to those used for online games. Real people are being killed in real time, but it all feels, from my standpoint at least, like World of Warcraft.

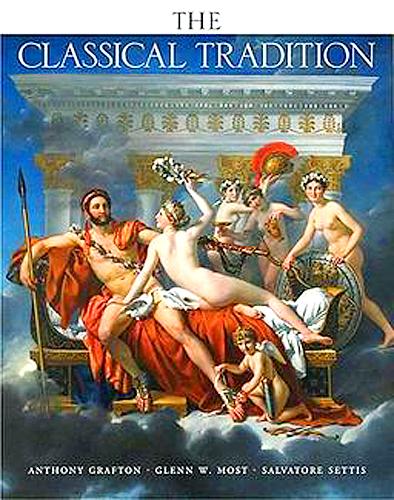

Then onto my desk falls The Classical Tradition, a stunningly wonderful compilation put together by classics teachers and experts, overwhelmingly from the US. Nothing could more perfectly represent the opposite of the hellish modern American world I’d become so obsessed with. Massive in length and unimpeachable in scholarship, it nonetheless manages to be endlessly absorbing, and often quietly entertaining into the bargain.

Its thousand and more pages are organized like an encyclopedia, with entries on all the great authors and many of the leading political figures of Greece and Rome, as well as topics such as baths, sexuality, vegetarianism (yes, there were ancient vegetarians), the color purple, Pan, the Elgin Marbles, and so on. I’ve counted 563 articles in all, penned by 339 contributors. I readily admit I haven’t read them all, but I’ve pored over this book like a madman ever since setting hands on it and I’ve devoured enough to be certain that it’s a masterpiece of concision, knowledge, judgment and dedication. It’s clearly going to be a companion for life, and all the better for being well-nigh inexhaustible.

The title The Classical Tradition has previously meant to me the magisterial book by Gilbert Highet, also an American and in his day a celebrated classics professor at Columbia. First published in 1949, its subtitle was Greek and Roman Influences on Western Literature. I’ve often thought that if I ever had to decide what one book to take with me to a desert island, this volume by Highet would be it, if only because it conjured up the spirit of so many other books and appeared endlessly re-readable.

The two books have a lot in common because the new one is also mainly concerned with the legacy of the Western classics. If you look up Propertius, for instance, you won’t find his works summarized in detail but rather an account of how his flagrantly provocative and sensational style and subject-matter were taken up in turn by John Donne, Ezra Pound and Robert Lowell. And if you look up Horace and Virgil — both choice entries kept in-house by one of the book’s editors, Glenn W. Most — you’ll find references to the Russian-American poet Joseph Brodsky as well as, at the end of the long Virgil article, evocations of four American poets contemplating in different ways their great Roman predecessor during World War II.

How many soldiers in Iraq or Afghanistan today are doing anything comparable, one wonders. None, I’d imagine. They’re all too busy on Twitter and Facebook.

The greatest period of rediscovery of Greece and Rome, of course, was the Renaissance. The Middle Ages had never forgotten them, however, and Dante made Virgil (representative of both the epic and of antiquity, as noted here) his guide through Hell and Purgatory in his Divine Comedy. Renaissance writers, nevertheless, figure very prominently in this new book, even to the extent of making you wonder whether our own age should be called one, not of a great rebirth, but of a great forgetting.

Attempts are made to counter such a depiction here — cinema and comic books are each subject of an article, for instance, with cinema seen as taking to the ancients far more extensively than comics, with Asterix as the most notable exception (and itself the subject of an entry). But even cinema has taken themes from ancient history far more frequently than it has from ancient literature.

This marvelous book, though, stands up for them both — the ancient world itself, and literature as the major art form. Is it still seen as such today? Probably not, but our editors take a longer view. What has been so for 3,000 years is not going to be swept away overnight: that is their implicit stance. Moreover, the main literary genres — drama, lyric and history — continue to dominate our consciousness, even if the dominant media have changed from the printed word to TV and pop music.

And in such a context, with artists recycling old themes from well before the age of Shakespeare, the conclusion is easy to reach that in essence almost everything worth saying has actually been said before. And, in the West, the people who said it first, and usually most memorably, were the Greeks and Romans.

I say this as someone who received not a shred of classical education. But it’s a conclusion I’ve come to slowly, and with the help of just such books as this one. Indeed, it’s for people like me, and not professional classicists, that this fine guide and companion was created. Long may it continue to be my Virgil through the gathering gloom!

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

In an interview posted online by United Daily News (UDN) on May 26, current Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) was asked about Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) replacing him as party chair. Though not yet officially running, by the customs of Taiwan politics, Lu has been signalling she is both running for party chair and to be the party’s 2028 presidential candidate. She told an international media outlet that she was considering a run. She also gave a speech in Keelung on national priorities and foreign affairs. For details, see the May 23 edition of this column,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

At Computex 2025, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) urged the government to subsidize AI. “All schools in Taiwan must integrate AI into their curricula,” he declared. A few months earlier, he said, “If I were a student today, I’d immediately start using tools like ChatGPT, Gemini Pro and Grok to learn, write and accelerate my thinking.” Huang sees the AI-bullet train leaving the station. And as one of its drivers, he’s worried about youth not getting on board — bad for their careers, and bad for his workforce. As a semiconductor supply-chain powerhouse and AI hub wannabe, Taiwan is seeing