A few years ago, critic Chuck Klosterman, writing about rock music, made an argument of the sort that can really disrupt a dinner party. Klosterman declared: “Given the choice between hearing a great band and seeing a cool band, I’ll take the latter every single time.” He didn’t add, but he might have, “Discuss.”

When he was in his late teens, David Bowie had little talent but cool to burn. His prettiness — think of Rob Lowe as an ethereal blond — was marred, provocatively, by his jagged and vampiric British teeth. A punch he’d taken as a schoolboy rendered one of his blue eyes permanently dilated, so it seemed to be a different color.

There was something alien and quickening about David Jones, as he was then still known, and people longed to gawk at him. He replaced more talented singers in bands because, well, that’s what cool kids do.

“When John sang, the kids kept on dancing,” a member of one of Bowie’s early bands said about its soon-to-be-replaced singer. “When David sang a number, they stopped to look.”

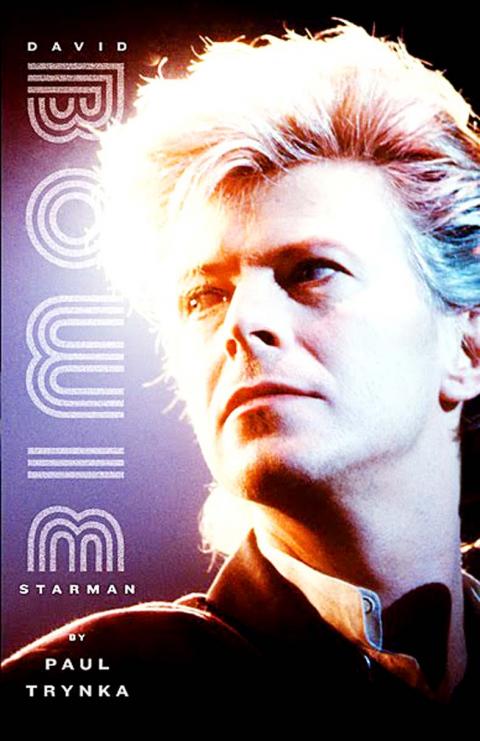

Girls looked; boys did, too. In his thoroughgoing new biography, David Bowie: Starman, British rock journalist Paul Trynka considers at length the startling androgyny that made Bowie a defining human being of the 1970s. About Bowie’s flamboyant alter ego, Ziggy Stardust, and his band, the Spiders From Mars, Trynka writes, these guys were “dangerous, a warning to lock up not only your daughters but also your sons.”

What cool giveth, cool can taketh away. By the time Bowie entered my consciousness in the early 1980s, when I was in high school, he’d gone mainstream, and I loathed him in a way that only an ardent young record buyer can loathe. His new hits — Let’s Dance, China Girl — blurted from car radios like flatulence. He did a Pepsi commercial. Trynka quotes music writer Charles Shaar Murray, wonderfully, about Bowie’s puzzling career choices during the 1980s. “I suddenly thought, he’s turned into a rock-and-roll version of Prince Charles,” Murray said, noting the “old-fashioned haircut like a lemon meringue on his head.”

I’ve since caught up, a bit, with Bowie’s earlier and best music, and I looked forward to David Bowie: Starman to hit the reset button on my sense of the man and his work. On that level, this book works. It pursues a number of galvanizing themes. It argues for Bowie less as an instinctive rocker than as a shape-shifting cabaret singer and composer writ large, a performer working in the tradition of Harold Arlen, Frank Sinatra, Hoagy Carmichael and Bertolt Brecht as well as the blues. Bowie was an outsider. Before him, the author writes, “pop music had been mainly about belonging.” His music meant so much to so many because it presented “a spectacle of not-belonging.”

The book depicts Bowie as charming but calculating and ruthless — a man who made few close friends and cared mostly about tending to what the author calls “Brand Bowie.” Morrissey, the singer, said about him: “He’s a business, you know. He’s not really a person.”

Bowie was not a natural singer or songwriter and toiled for his success. He has a good ear, so good that some of his best material, the author argues, pickpocketed the work of others. Trynka notes how closely Bowie’s song Starman resembles Over the Rainbow. Bowie’s hit The Jean Genie pilfered a riff from Muddy Waters’ I’m a Man. The song Life on Mars borrowed a chord sequence from a French song called Comme d’Habitude, later reworked into English by Paul Anka as My Way.

David Bowie: Starman is a better-than-average rock biography, but just barely. It’s patient and respectable without being quite likable, without ever quite becoming your friend. When you put this heavy thing down, it doesn’t call out to be seized back up again quickly. You may begin to circle its bulk warily.

The critic in Trynka too rarely emerges. Midway through, I began to realize that the Bowie book I longed to read would be similar to Greil Marcus’ recent assessment of Van Morrison, the shrewdly essayistic When That Rough God Goes Riding. I wanted a critic’s case for Bowie, to be guided through his most transcendent work.

One can’t blame an author for not writing a book he didn’t write, however. And many moments in David Bowie: Starman made me lean forward with pleasure. Trynka has a way with a phrase. Writing about an early sexual experience Bowie supposedly had with a boy named Mike, the author doesn’t simply say the two of them made out. He writes, “Mike had investigated the contents of David’s trousers.”

About The Laughing Gnome, a terrible early song of Bowie’s, the author says, “As long as one is happy to abandon all notions of taste, the song is brilliantly crafted.” Even better, he adds about this song, “In the admittedly narrow niche of pseudopsychedelic cockney music-hall children’s songs, it reigns supreme.” The author quotes others well, too, a quality I admire. A friend of Bowie’s, talking about the absurd amount of sex that went on in the singer’s home, reports, “I used to wake under a pile of bodies.”

Bowie was born David Robert Jones on Jan. 8, 1947, in the postwar gloom and rubble of the Brixton district of south London. His family was middle class. His father had owned a theater troupe and invested in a nightclub before going to work for a children’s charity. His mother, his father’s second wife, had been a waitress. Bowie had two siblings, a half-brother named Terry and a half-sister named Annette.

While contemporaries like Keith Richards were spellbound by rural US bluesmen like Muddy Waters, Bowie’s early hero was Little Richard, a rowdy boy of indefinite sexuality. The young David Jones played with, and discarded, several bands before deciding to go solo and change his last name to Bowie, after the Texas folk hero Jim Bowie, played by Richard Widmark in the film The Alamo.

David Bowie, now 64 and married to the Somali-born model Iman, hasn’t released a studio album since 2003 and in 2004 had emergency angioplasty for a blocked artery.

“For the fans,” Trynka writes, “Bowie’s continuing absence seemed an almost unforgivable desertion.”

The epilogue of David Bowie: Starman contains this sanguine observation, however: “In 2012, his back catalog will be available for license once more, and many fans hope to see what is thought to be the most intriguing set of unreleased recordings of audio and video outtakes of any major recording artist.”

David Bowie’s greatness, this book suggests, more than caught up with his coolness.

The unexpected collapse of the recall campaigns is being viewed through many lenses, most of them skewed and self-absorbed. The international media unsurprisingly focuses on what they perceive as the message that Taiwanese voters were sending in the failure of the mass recall, especially to China, the US and to friendly Western nations. This made some sense prior to early last month. One of the main arguments used by recall campaigners for recalling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers was that they were too pro-China, and by extension not to be trusted with defending the nation. Also by extension, that argument could be

Aug. 4 to Aug. 10 When Coca-Cola finally pushed its way into Taiwan’s market in 1968, it allegedly vowed to wipe out its major domestic rival Hey Song within five years. But Hey Song, which began as a manual operation in a family cow shed in 1925, had proven its resilience, surviving numerous setbacks — including the loss of autonomy and nearly all its assets due to the Japanese colonial government’s wartime economic policy. By the 1960s, Hey Song had risen to the top of Taiwan’s beverage industry. This success was driven not only by president Chang Wen-chi’s

Last week, on the heels of the recall election that turned out so badly for Taiwan, came the news that US President Donald Trump had blocked the transit of President William Lai (賴清德) through the US on his way to Latin America. A few days later the international media reported that in June a scheduled visit by Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) for high level meetings was canceled by the US after China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平) asked Trump to curb US engagement with Taiwan during a June phone call. The cancellation of Lai’s transit was a gaudy

The centuries-old fiery Chinese spirit baijiu (白酒), long associated with business dinners, is being reshaped to appeal to younger generations as its makers adapt to changing times. Mostly distilled from sorghum, the clear but pungent liquor contains as much as 60 percent alcohol. It’s the usual choice for toasts of gan bei (乾杯), the Chinese expression for bottoms up, and raucous drinking games. “If you like to drink spirits and you’ve never had baijiu, it’s kind of like eating noodles but you’ve never had spaghetti,” said Jim Boyce, a Canadian writer and wine expert who founded World Baijiu Day a decade