When Gabrielle Hamilton was a child, growing up in Pennsylvania, her family gave an annual party that was legendary in its small town — a spring lamb roast for almost 200 people, who came from as far away as New York City: former ballet dancer friends of her mother’s and artist friends of her father’s, along with local friends and neighbors, who all gathered in the meadow behind their house to feast on lamb and asparagus vinaigrette and shortcake. In preparation Gabrielle and her sister and brothers would fill dozens of brown paper lunch bags with sand and candles, set them along the stream’s edge under the weeping willows to light everyone’s way, and juice up glow-in-the-dark Frisbees in the car headlights, so they could send those “glowing greenish discs arcing through the jet black night.”

The pastoral idyll of Hamilton’s childhood was abruptly shattered when her parents separated, and memories of their “luminous parties” and the meals they’d shared as a family would shape her adult life, from her marriage into an Italian family that shared her passion for food to her opening of a New York City restaurant named Prune, which would win kudos from critics for its homey, rustic cooking.

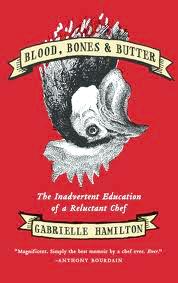

Though Hamilton’s brilliantly written new memoir, Blood, Bones & Butter, is rhapsodic about food — in every variety, from the humble egg-on-a-roll sandwich served by Greek delis in New York to more esoteric things like “fried zucchini agrodolce with fresh mint and hot chili flakes” — the book is hardly just for foodies. Hamilton, who has an MFA in fiction writing from the University of Michigan, is as evocative writing about people and places as she is at writing about cooking, and her memoir does as dazzling a job of summoning her lost childhood as Mary Karr’s Liars’ Club and Andre Aciman’s Out of Egypt did with theirs.

Hamilton nimbly cranks up her own literary time machine to transport us back to the hippie-ish world of rural Pennsylvania in the 1970s, and to New York City at the height of the coke-and-urban-cowboy era of the 1980s. She conveys what it was like to be a rebellious delinquent in the making, arriving by Peter Pan bus at Hampshire College — where everyone was “discussing third world feminism, doing shifts at the on-campus food co-op and building eco-yurts for academic credit” — and what it was like to be young and poor in Manhattan, surviving on stolen ketchup packets from McDonalds on Eighth Avenue and going to “Village Voice advertised bars that held happy hours with free hot hors d’oeuvres.”

With a couple of sentences Hamilton effortlessly captures her father’s sorcery as a set designer and the world of make-believe she and her siblings got to inhabit: his scenery-building studio, where there were “oil drums full of glitter” and “mountains of rolled black and blue velour” laid out like carpets. And the extravagant parties he helped produce like the Valentine’s Day Lovers’ Dinner at which he had “hundreds of choux paste eclair swans with little pastry wings and necks and slivered almond beaks” swimming, in pairs, on a “Plexiglas mirror ‘pond’ the size of a king’s matrimonial bed with confectioner’s sugar snow drifts on the banks.”

Fiercely conjured as well is the sudden tumble in dislocation and dysfunction that the young Hamilton and her 17-year-old brother, Simon, experienced in the wake of their parents’ breakup, when they were left alone in the house to fend for themselves for a summer.

She describes shoplifting and doing coke at the age of 13 and breaking into neighbors’ houses and stealing things she could pawn in town. She describes foraging in her mother’s pantry — which her father had not cleaned out, “the way a griever won’t empty the clothes closet of the deceased spouse” — and learning to improvise meals out of canned sardines and tinned asparagus. And she describes getting kitchen experience at a restaurant “called, ironically, Mother’s,” where she washed dishes, helped with salads, and, in time, “made it on to the hot line.”

There are some odd gaps and puzzling emotional elisions in this memoir. While Hamilton says her mother taught her “everything I know, pretty much, about eating, cooking, and cleaning” and describes her mother as being “the very heartbeat of the most cherished period” of her life, she abruptly notes in the middle of the book that she had not seen her mom in 20 years; she says she cannot explain their lack of communication except to observe, “I feel better without her.” There is similarly not a lot of detail about what happened to her father and her other siblings (with the exception of her sister, Melissa, with whom she stayed in New York City) after her parents’ divorce.

The through-line in this volume remains Hamilton’s efforts to recapture the magic of her childhood, and her love of food, which would culminate in the decision to open a restaurant of her own in 1999. Readers who don’t log a lot of time with the Food Network may find some of her self-dramatized emotions baffling — like developing an urgent craving for “broccoli rabe with pepperoncini and braised rabbit” while driving around Brooklyn with her family, and warning that her hunger is becoming a “Code Red.” Still, Hamilton proves adept at using tactile, aromatic prose to chronicle her apprenticeship as a cook: from the basics she learned from her mother, to her work with various catering companies (descriptions of which will make many readers hesitate before wolfing down a prettily arranged tidbit at the next catered event) to her adventures in eating around the world as a virtually penniless backpacker often dependent on the kindness of strangers.

The driving impulse behind her determination to open a restaurant, she explains, was to “harness a hundred pivotal experiences relating to food — including hunger and worry — and translate those experiences into actual plates of food,” to reproduce the sort of hospitality she’d experienced traveling “from Brussels to Burma,” in a 30-seat restaurant in “the as-yet-ungentrified and still heavily graffitied East Village,” to give guests the sort of primal food experience that existed in small towns around the world, long before snooty words like “artisanal,” “organic,” “diver-picked,” “free-range” and “heirloom” became trendy seals of approval in big-city restaurants.

Blood, Bones & Butter: The Inadvertent Education of A Reluctant

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by