Nearly 40 years after his death, Bruce Lee (李小龍) remains very much alive in the public’s imagination. While most people remember him as a kung fu legend in a yellow jumpsuit, Hong Kong directors Raymond Yip (葉偉民) and Manfred Wong (文雋) set out to shed new light on the star’s lesser known early life in Bruce Lee, My Brother (李小龍), a fictionalized biography of the star based on the memoir written by his younger brother, Robert Lee Jan-fai (李振輝).

Sadly, the production fails to capitalize on its admirable credentials. The script is unfocused, the subplots vary greatly in tone, and the choppy narrative fails to present a coherent or comprehensive look at the first 19 years of the action legend’s life before he left Hong Kong for the US.

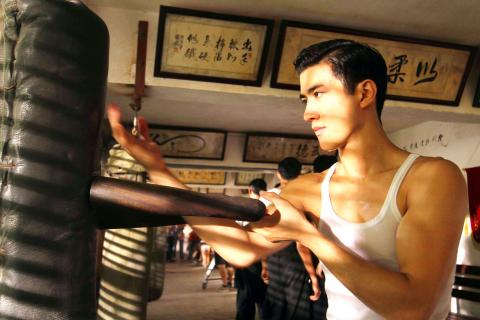

The film begins with an introduction by the real Robert Lee, who stresses that the story, though dramatized, is based on the true story of his elder brother and their family, which sets the tone for a saga. New talent Aarif Rahman (李治廷) is cast as the teenage Bruce, who grows up in a bustling household surrounded by countless relatives, family friends and childhood pals. The references to Bruce’s earliest acting experiences as a child and teenage star, such as restaged scenes from The Kid (細路祥, 1950) and Thunderstorm (雷雨, 1957), are amusing to watch, and there are plenty of celebrity cameos embodying the luminaries and movie icons of 1950s Hong Kong cinema.

Photo Courtesy of Applause Pictures

Much of the screen time is spent on examining Bruce’s experience with young love and his misadventures as a mischievous lad with a penchant for street fighting. On several occasions, the filmmakers pay tribute to the star’s kung fu classics in sequences where the young Bruce clinches his fist in anger when facing a sneering Chinese police officer (remember the Chinese villain in Fist of Fury (精武門)?) or takes on a loudmouthed British boxer (as in Way of the Dragon (猛龍過江)).

At its most exaggerated moment, the film features drug dealers that Bruce has to rescue a junkie friend from, leading to a scaffold-climbing action sequence that resembles excerpts from the newest Chinese action blockbusters.

As a result, the purportedly biographical flick suffers greatly from a narrative that awkwardly oscillates between glamorized storytelling and references to actual events and historical context. The screen is filled with anecdotes and details that are diverting but formulaic. The film happily romps from one youthful episode to another, refusing to delve into how the kung fu legend’s childhood and adolescence shape his character and influence his martial arts and filmmaking later in life. Bruce Lee fans will be dismayed to see that the sequence in which the future legend becomes the disciple of wing chun (詠春) master Yip Man (葉問) — who is curiously shown only in silhouette — is downplayed as just part of Bruce’s training to fight the British boxer.

Photo Courtesy of Applause Pictures

In a strange way, the film manages to stay true to its provenance — the faded childhood memory of Bruce Lee’s now gray-haired baby brother Robert Lee, who was understandably too young to understand the significance of the events that took place during the star’s formative years. From the get-go, Bruce Lee, My Brother was destined to become a cinematic pastiche of fragmented memories, family stories, the star’s onscreen image and the popular legends and myths that will forever surround the late martial arts master.

Photo Courtesy of Applause Pictures

Aug. 4 to Aug. 10 When Coca-Cola finally pushed its way into Taiwan’s market in 1968, it allegedly vowed to wipe out its major domestic rival Hey Song within five years. But Hey Song, which began as a manual operation in a family cow shed in 1925, had proven its resilience, surviving numerous setbacks — including the loss of autonomy and nearly all its assets due to the Japanese colonial government’s wartime economic policy. By the 1960s, Hey Song had risen to the top of Taiwan’s beverage industry. This success was driven not only by president Chang Wen-chi’s

Last week, on the heels of the recall election that turned out so badly for Taiwan, came the news that US President Donald Trump had blocked the transit of President William Lai (賴清德) through the US on his way to Latin America. A few days later the international media reported that in June a scheduled visit by Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) for high level meetings was canceled by the US after China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平) asked Trump to curb US engagement with Taiwan during a June phone call. The cancellation of Lai’s transit was a gaudy

From Godzilla’s fiery atomic breath to post-apocalyptic anime and harrowing depictions of radiation sickness, the influence of the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki runs deep in Japanese popular culture. In the 80 years since the World War II attacks, stories of destruction and mutation have been fused with fears around natural disasters and, more recently, the Fukushima crisis. Classic manga and anime series Astro Boy is called “Mighty Atom” in Japanese, while city-leveling explosions loom large in other titles such as Akira, Neon Genesis Evangelion and Attack on Titan. “Living through tremendous pain” and overcoming trauma is a recurrent theme in Japan’s

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in