The death of Michael Jackson in June prompted a frenzy of publishing activity, and bookshops were buried under piles of at least half-a-dozen new titles long before his family actually got around to burying the erstwhile king of pop. Top of the heap was Michael Jackson 1958-2009 — Life of a Legend (Headline) by Michael Heatley, which spent four weeks at No 1 in the Nielsen BookScan chart and has sold 35,000 copies in the UK and 150,000 copies worldwide, to date.

Heatley, an author who has somehow found time to write more than 100 biographies on subjects ranging from the British radio DJ John Peel to Rolf Harris, is not given to agonizing over matters of nuance, let alone literary style. His book provides a functional, sympathetic resume of Jackson’s life, and reads rather like an extended obituary designed to resonate with fans of the singer. The story of Jackson’s astonishing career is celebrated as much through hundreds of pictures and their accompanying captions as by the text itself, while the murkier side of his private life is afforded a cursory mention only where unavoidable.

Of the other books commemorating the singer’s demise, Michael Jackson — The King of Pop 1958-2009 by Chris Roberts (Carlton) merits a mention for its fractionally more trenchant tone and mildly enquiring approach. However, in terms of genuine insight and vitality, none of them compares to Jackson’s own, often overlooked account of his life, Moonwalk (William Heinemann). Written in 1988, Moonwalk was republished in October with an added foreword by the founder of Motown, Berry Gordy, and an intriguing postscript by Shaye Areheart, one of the book’s original editors. Having been cajoled and assisted by a team of dedicated professionals over four years, Jacko produced a surprisingly lucid and occasionally revealing account of what it was actually like to be him.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Another deceased superstar was put under the biographical microscope in Bob Marley — The Untold Story (Harper Collins) by Chris Salewicz. While Jackson is considered to be a tarnished idol by all but his most ardent supporters, Marley’s premature demise at the age of 36 has conferred a saintly status on the reggae star, which Salewicz is happy to indulge. “Some will come out and say it directly: that Bob Marley is the reincarnation of Jesus Christ,” he declares, before flagging up various conspiracy theories to explain the sudden onset of the cancer that was to claim his life, thereby turning the story into “a modern version of the crucifixion”.

Salewicz’s boundless respect for his subject is a plus when it comes to his knowledge and understanding of Marley’s Jamaican heritage and a detailed appreciation of his musical accomplishments, but is a bit disconcerting when it comes to matters of Marley’s all-too-human failings. The author reports without comment an occasion when Marley “beat his wife [Rita] around the hotel suite” resulting in a very large bill “for repairs to assorted fixtures and fittings,” and notes that, while married to her, the musician fathered 13 children by eight different women. “Who knows what emotional and psychological complications . . . were involved?” Salewicz ponders, referring to Bob of course, not Rita.

Emotional and psychological complications are the engine that drives Bad Vibes — Britpop and My Part in Its Downfall (Windmill), the outrageously indiscreet memoirs of the singer and songwriter Luke Haines. Aggressive, vainglorious, insecure and forever teetering on the brink of another meltdown, Haines strides (or hobbles) through a highly personalized account of the great Britpop wars of the 1990s, insulting virtually everyone involved. While Oasis, Blur and Suede rule the charts, Haines hangs around on the fringes in his own groups the Auteurs and, later, the Baader Meinhof Gang, too cool or too wasted to embrace success even when offered to him on a plate. Bad Vibes turns casual misanthropy into an art form, and makes a brilliant read in the process.

When it comes to heroic failures, however, even Haines cannot compare with the Canadian heavy metal group Anvil, whose rags to more rags story is chronicled in merciless detail in Anvil — The Story of Anvil (Bantam Press). The band for whom great things were just around the corner in the early 1980s have plodded on to the present day, finally achieving recognition of sorts thanks to a film which portrayed them as something akin to the real Spinal Tap. The book, which is basically parallel autobiographies by the guitarist Lips Kudlow and drummer Robb Reiner, fills in a lot of details that were glossed over in the movie, providing a step-by-step guide on precisely how to blow it in the music business. The story is funny and sad but also strangely heartwarming as this guileless pair continue to place their trust in each other and the belief that things are just about to get better in the face of sustained and overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

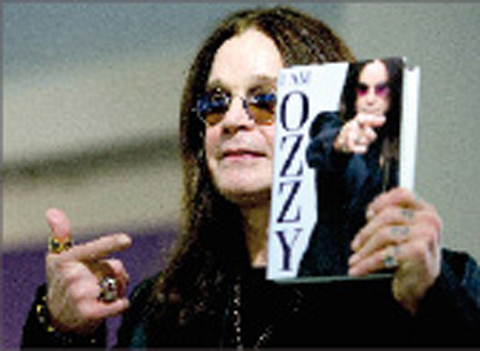

For heavy metal buffoonery on a cosmic scale, there is not much to beat I Am Ozzy (Sphere), the autobiography of Ozzy Osbourne. From unpromising beginnings as a prisoner (by the age of 18) and then a slaughterhouse worker, Osbourne has somehow carved out a career as an international reality TV celebrity, having invented the heavy metal genre during his time as a founder member of Black Sabbath. He was, by his own account, out of his head at every step of the way, and owes it all to the efforts of the people around him, together with an uncanny knack for holding people’s attention. What could the guys from Anvil have achieved had they been blessed with even an ounce of such dumb luck?

It’s not often you get to hear the drummer’s side of the story, but books by two percussion pioneers appeared this year. Ginger Baker’s Hellraiser (John Blake) — modestly subtitled “The Autobiography of the World’s Greatest Drummer” — gives a blow by blow account of a long and rather spotty career during which less than three years were spent with Eric Clapton and Jack Bruce in the 1960s supergroup Cream. Baker, now aged 70, is not a man to forget a grudge, and many old scores are settled — particularly with Bruce — in this cantankerous account.

In contrast to Baker’s rough and ready approach, Bill Bruford — The Autobiography (Jawbone) is an unusually literate and reflective work which dissects the drummer’s art, and the dilemmas faced by modern musicians in general, with an almost surgical precision. But while the former Yes and King Crimson drummer’s tale is more elegantly expressed, by the end of it Bruford is just as pissed off as Baker and all the others. Pondering his decision to retire (at the age of 59) he concludes: “I know too much and can think of nothing to play. Best be silent, then.”

NOTE: David Sinclair’s Wannabe: The Spice Girls Revisited is published by Omnibus

Wooden houses wedged between concrete, crumbling brick facades with roofs gaping to the sky, and tiled art deco buildings down narrow alleyways: Taichung Central District’s (中區) aging architecture reveals both the allure and reality of the old downtown. From Indigenous settlement to capital under Qing Dynasty rule through to Japanese colonization, Taichung’s Central District holds a long and layered history. The bygone beauty of its streets once earned it the nickname “Little Kyoto.” Since the late eighties, however, the shifting of economic and government centers westward signaled a gradual decline in the area’s evolving fortunes. With the regeneration of the once

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

In February of this year the Taipei Times reported on the visit of Lienchiang County Commissioner Wang Chung-ming (王忠銘) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a delegation to a lantern festival in Fuzhou’s Mawei District in Fujian Province. “Today, Mawei and Matsu jointly marked the lantern festival,” Wang was quoted as saying, adding that both sides “being of one people,” is a cause for joy. Wang was passing around a common claim of officials of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the PRC’s allies and supporters in Taiwan — KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party — and elsewhere: Taiwan and

Perched on Thailand’s border with Myanmar, Arunothai is a dusty crossroads town, a nowheresville that could be the setting of some Southeast Asian spaghetti Western. Its main street is the final, dead-end section of the two-lane highway from Chiang Mai, Thailand’s second largest city 120kms south, and the heart of the kingdom’s mountainous north. At the town boundary, a Chinese-style arch capped with dragons also bears Thai script declaring fealty to Bangkok’s royal family: “Long live the King!” Further on, Chinese lanterns line the main street, and on the hillsides, courtyard homes sit among warrens of narrow, winding alleyways and