The Boat, the first book of Vietnamese-born Nam Le, has taken the English-speaking literary world by storm, certainly in Australia and the US. The author left Vietnam when very young and eventually arrived in Australia. He subsequently began work as a lawyer but gave that up to enroll in creative-writing courses in the US. He now divides his time between these two countries.

The book consists of seven short stories (itself unusual for a first publication) and each of them is entirely different — in setting, style, and the point of view of the narrator or principal character. Only the first and last stories, both immensely strong, feature Vietnam, though neither has it as its principal location. Others are set in Colombia, Iran, Japan, Australia and the US.

Every story is a tour de force of imaginative sympathy and thoughtfulness. The one set in Japan, for example, is entirely phrased in the words of a small girl in Hiroshima in the days before the unleashing of the atomic bomb — she talks with gentle innocence of butterflies, flowers, the revered emperor, the war effort, and the lack of danger posed by single American aircraft — they only drop leaflets that it’s forbidden to read, she muses as she plays in the dust.

The Colombia story is set in the drug capital of Medellin and is narrated by a teenager with orders from his gangland boss to kill his best friend. Grenades, pistols and machine guns are part of his everyday life, but by an extraordinary effort of empathy he’s presented by the author as the adolescent he is, and with an adolescent’s attitudes and loyalties, but forced into a terrifyingly adult predicament.

The story set in Teheran features an American woman who’s visiting an Iranian friend she got to know in the US. She labors under multiple levels of incomprehension, and yet Iranian society is displayed in extraordinary detail — the food, the furnishings, the views from the city, the religious and other customs. I found it the least satisfying of the stories because I didn’t understand why it ended as it did, but even so overall this is a quite exceptional book.

Nam Le is something of an intellectual writer — his vocabulary is extensive and even occasionally abstruse, and one of his greater strengths is giving characters the ability to look deep into themselves and ponder on why they’re thinking as they are. But there’s nothing whatsoever pale or abstract about these stories, none of Colm Toibin’s willingness to leave stories without a traditional ending or of Kazuo Ishiguro’s trademark understatement. Instead, violence is everywhere in this book, sometimes on the surface but, if not, then just beneath it.

The opening and closing stories featuring recent Vietnamese history are terrifying. In the first a student of Vietnamese extraction is studying on a creative-writing course in Iowa (exactly as Nam Le did — and this ability to be quasi-autobiographical in one story, and then write about a country he’s never even been to in another, is part of his enviable strength as a writer). His father is visiting Iowa, and he’s made to be a survivor of the My Lai massacre. This enables Nam Le to juxtapose young American GIs then — one in a bead necklace and baseball cap who taps his grandfather on the top of his head with his rifle butt, then twirls round and slides his bayonet into his throat — with his contemporaries at Iowa, making jokes about his “ethnic” stories and how much money he can make from them.

The last item features 200 Vietnamese emigrants in the 1980s on a fishing boat built for a crew of 15. Horror is piled on horror — storms, excrement, suicides, disease, broken-down engines, no drinking water (let alone food) and sharks. Yet curiously there’s nothing intrinsically sensational about Nam Le’s writing. These things happened, and they’re part of our world, he implies, as are seagulls with their stomachs torn out by fishermen’s hooks, child soldiers, and raped and then executed children.

In place of sensationalism, Nam Le looks inside his characters. His refugees, for instance, aren’t simply anonymous figures but lonely and jealous husbands, women with secrets, individuals with war-torn minds who set out together on a leaky wooden ship into mountainous seas, with worse to follow.

Nevertheless, this book doesn’t really have any political ax to grind. Instead, Nam Le is saying, “Just look! These victims, from all over the world and often very young, were all partway through their real and only lives, yet were subjected to laceration and death for reasons wholly beyond their control or comprehension. And this could be you, or me, and one day it may be.”

But even that is too specific. Each of these seven stories is different, but they do share the results of thinking unflinchingly on the harsh conditions of human existence. There are some discernible themes — difficult relations between parent and child is one of them, present in four of the seven stories. But there’s also the serious writer’s technical desire to create things that are coherent in themselves, but are also distinct from anything that he’s imagined and written before.

That this book is the debut of a major writer is unquestionable. It isn’t only that Nam Le often writes with immense power. He’s also uncompromising (and hence occasionally difficult to follow), in deadly earnest, and writes about the age-old concerns of the greatest artists — love, death, fear, hope, and the profoundest human dilemmas.

When asked in an interview what the strongest fiction was that he’d read that year, Nam Le replied “Cormac McCarthy’s The Road”. Coming from such an impeccable source, I for one won’t need any stronger recommendation.

During the Metal Ages, prior to the arrival of the Dutch and Chinese, a great shift took place in indigenous material culture. Glass and agate beads, introduced after 400BC, completely replaced Taiwanese nephrite (jade) as the ornamental materials of choice, anthropologist Liu Jiun-Yu (劉俊昱) of the University of Washington wrote in a 2023 article. He added of the island’s modern indigenous peoples: “They are the descendants of prehistoric Formosans but have no nephrite-using cultures.” Moderns squint at that dynamic era of trade and cultural change through the mutually supporting lenses of later settler-colonialism and imperial power, which treated the indigenous as

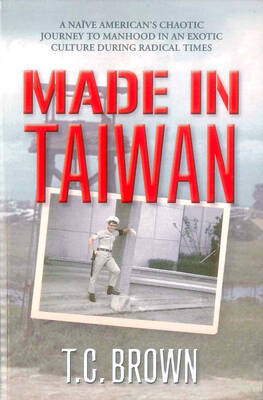

By 1971, heroin and opium use among US troops fighting in Vietnam had reached epidemic proportions, with 42 percent of American servicemen saying they’d tried opioids at least once and around 20 percent claiming some level of addiction, according to the US Department of Defense. Though heroin use by US troops has been little discussed in the context of Taiwan, these and other drugs — produced in part by rogue Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) armies then in Thailand and Myanmar — also spread to US military bases on the island, where soldiers were often stoned or high. American military policeman

An attempt to promote friendship between Japan and countries in Africa has transformed into a xenophobic row about migration after inaccurate media reports suggested the scheme would lead to a “flood of immigrants.” The controversy erupted after the Japan International Cooperation Agency, or JICA, said this month it had designated four Japanese cities as “Africa hometowns” for partner countries in Africa: Mozambique, Nigeria, Ghana and Tanzania. The program, announced at the end of an international conference on African development in Yokohama, will involve personnel exchanges and events to foster closer ties between the four regional Japanese cities — Imabari, Kisarazu, Sanjo and

The Venice Film Festival kicked off with the world premiere of Paolo Sorrentino’s La Grazia Wednesday night on the Lido. The opening ceremony of the festival also saw Francis Ford Coppola presenting filmmaker Werner Herzog with a lifetime achievement prize. The 82nd edition of the glamorous international film festival is playing host to many Hollywood stars, including George Clooney, Julia Roberts and Dwayne Johnson, and famed auteurs, from Guillermo del Toro to Kathryn Bigelow, who all have films debuting over the next 10 days. The conflict in Gaza has also already been an everpresent topic both outside the festival’s walls, where