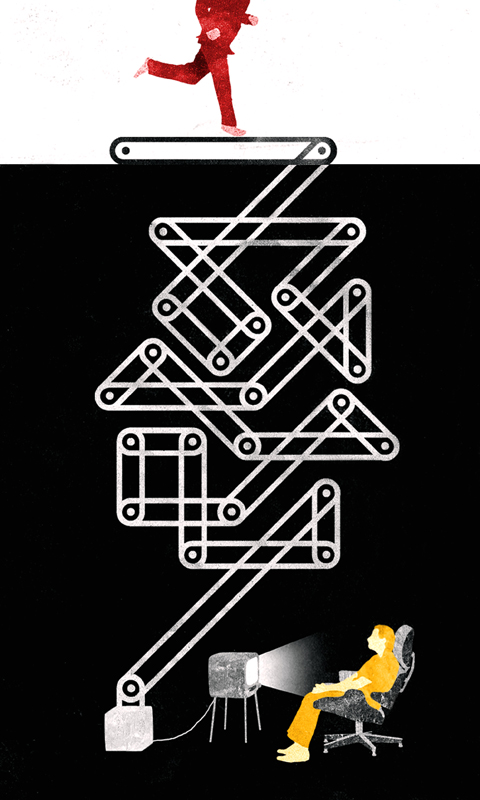

Each year hundreds of thousands of Americans, including some 700,000 Medicare recipients, get on a treadmill not for exercise but to try to determine if their hearts are healthy.

Tim Russert, the NBC journalist, had such an exam, called an exercise or treadmill stress test, six weeks before he died of a heart attack last month at age 58. His results had been deemed normal, prompting people to question how worthwhile this test could be.

Two weeks before Russert died, Todd D. Miller, a cardiologist and co-director of the Mayo Clinic’s Nuclear Cardiology Laboratory in Rochester, Minnesota, published an assessment of the test’s ability to predict the presence of potentially life-threatening cardiac problems. Miller elaborated on his report, in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, in a telephone interview.

ILLUSTRATION: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

The test is meant to be used “almost exclusively” for people who have symptoms of heart disease, Miller emphasized.

“But in the real world,” he said, “it is often used as a screening test for people without symptoms who are worried about their risk. The accuracy of the test depends on whom it is used. It is most accurate among populations with a high prevalence of coronary disease. But in most people without symptoms, the prevalence of disease is so low that the accuracy of the test is low, too.”

LIMITATIONS AND ADVANTAGES

In fact, this test is unable to detect the kind of problem that caused Russert’s death — a plaque within the wall of a coronary artery that ruptured, resulting in a clot that set off a rapidly fatal heart rhythm abnormality. If not for the rhythm disturbance, Russert would have had a far greater chance of surviving his heart attack, said Miller, who was not one of his physicians.

Russert’s treadmill test may have put him in the low-risk category, Miller said, “but that doesn’t mean no risk.”

“Maybe three patients in 1,000 with a low-risk test will die from heart disease within a year,” he said. “Among those deemed at high risk, more than three patients in 100 would die within a year.”

Furthermore, when the stress test is used for people who are at low risk for heart disease, an abnormal finding is most often a false positive that prompts further testing that is far more costly, Miller said.

The stress test’s main advantages are its rapidity and low cost — one-fifth to one-quarter the cost of more definitive and often more time-consuming tests like a nuclear stress test, CT coronary angiogram or standard angiogram. In the US, Medicare pays about US$150 for a standard stress test, though hospitals typically charge three to four times that when the test is done on younger patients.

Regardless of cost, the test has no value unless its findings are interpreted in the context of a person’s other risk factors for heart disease: age, sex and heart disease symptoms, as well as smoking, being overweight, hypertension, high cholesterol, diabetes and family history.

Three main arteries feed the heart, and the ability of a stress test to pick up narrowing of an artery depends on which one is involved, Miller said. It is better at picking up coronary disease if more than one artery is clogged.

The treadmill test seeks to answer two questions: “Does the patient have coronary artery disease, and is he or she likely to die or suffer a coronary event soon?” Miller wrote in the Cleveland Clinic journal. But at best it can provide only an estimate of someone’s risk of having a heart attack or dying of heart disease within a given period of time.

INTERPRETING THE RESULTS

During a treadmill test, patients are hooked up to an electrocardiogram machine (often abbreviated EKG, for the German spelling) that records the workings of the heart as the duration, speed and difficulty of the exercise increase.

Measurements taken during and immediately after the workout are indicators of cardiovascular fitness and how well a person’s autonomic nervous system is functioning: how long the person can continue as the treadmill’s speed and incline gradually increase; whether blood pressure drops instead of rising; whether the heart rate increases to an age-appropriate level and how fast it recovers when the test ends; and whether the pumping chambers of the heart develop abnormal beats.

Doctors used to rely mainly on an EKG finding called ST-segment depression to indicate heart trouble. But scores of studies have zeroed in on other, more reliable findings. Exercise duration has the strongest prognostic value, Miller said. “The longer the patient can keep going on the treadmill, the less likely he or she is to die soon of coronary artery disease — or of any cause,” he wrote.

Even people who have three diseased coronary arteries can be expected to survive four years or more if they can stay on the treadmill for 12 or more minutes, a study in the 1980s of 4,083 patients with symptoms of heart disease showed.

But duration on the treadmill may be limited by lack of physical fitness, back problems or other unrelated disorders, leading to other, more expensive evaluations.

“When a middle-age couch potato is done in after only three minutes on the treadmill, you scratch your head,” Miller said. “Is this heart disease or just deconditioning?”

MEASUREMENTS AND DIAGNOSES

Duration on a treadmill is a measure of exercise capacity — the workload the body can achieve expressed as metabolic equivalents, or METs, a multiple of the amount of oxygen the body uses at rest. The average middle-age man can reach 10 METs to 12 METs, about 2 METs more than the average woman, Miller said.

Blood pressure that is lower during the treadmill exercise than when the person is standing at rest often indicates severe coronary disease — a heart unable to meet the demand — and has been linked to a threefold increase in the risk of a cardiac event within two years, a study of 2,036 patients showed.

A normal heart beats faster during exercise and slows as soon as exercise stops. Failure of the heart rate to increase as expected, a condition called chronotropic incompetence, is associated with an increased risk of death from heart disease, a study by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation showed. The risk of death within six years is also doubled if the person’s heart rate fails to fall quickly when the treadmill stops.

Finally, various heart rhythm abnormalities may occur during the treadmill test. Though most are benign, a rhythm disturbance after the test called ventricular ectopy is linked to a somewhat raised death rate over the next five years.

The bottom line? A stress test result is only one factor in estimating a person’s risk of dying soon of heart disease. All other risk factors must be taken into account and, if possible, treated to reduce or eliminate them. To this advice Miller added, “We’d all be a lot better off if we became more active.”

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by