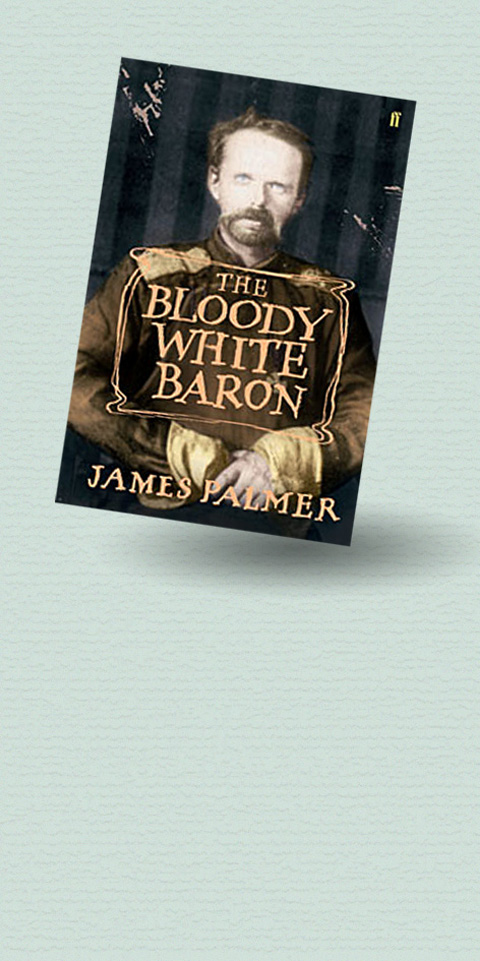

Usually, when a biographer has failed to find sources that take the reader inside the head of his subject, it is a disappointment. In the case of Baron Roman Ungern von Sternberg, however, one can only feel intensely relieved that James Palmer has been unable to come up with an intimate diary, a memoir from a mistress or letter home to Mom. For Ungern appears to have been so unpleasantly mad (think keeping people up trees for days at a time or sending them on patrol naked on the Siberian ice) that in any other era he would have been committed to a genteel asylum somewhere in a foresty bit of middle Europe where his fantasy that he was the reincarnation of Genghis Khan would have been tolerated with a wry smile and a very large bunch of keys.

Ungern didn’t start out mad, although he does seem to have been really quite bad from the get-go. Born in 1885 into one of those aristocratic Baltic German clans that had staffed the imperial Russian court and army for centuries, Ungern was expelled from pretty much every elite educational and training institution open to him. Still, he managed to creep into the Russian army in order to serve in the Russo-Japanese conflict of 1904, and from there he levered himself a spot as a cavalry general in World War I, which followed shortly after.

When the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917 Ungern joined the Whites in the Far East and served under the equally bonkers Semenov, who by now had the backing of, confusingly, the Japanese. Appointed governor of the Siberian town of Dauria, and no longer considering himself beholden to anyone, Ungern set about creating a private army consisting of 16 nationalities, including Cossacks and plain old Russians. The objectives of this raggle-taggle crew were to restore the late Tsar’s brother to the imperial throne, recreate the glory days of Genghis Khan’s empire, and uphold the rule of the living god-king, Bogd Khan, in Mongolia.

This last ambition was key. For underpinning Ungern’s program was a fanatically held belief in Buddhism. And, in case that sounds like a massive contradiction, Palmer is on hand to remind us that Buddhism, especially in its Tibetan and Mongolian guises, has always been as politically dirty as any other world religion. Far from being a charter for godless, rational serenity, the kind of Buddhism in which Ungern believed was a war-mongering pantheism with peaks of refined cruelty. Even the Dalai Lama of the time turns out to have been a baddy.

This license to be mean came in handy in 1921, when Ungern and his army stormed into Mongolia and declared it an independent kingdom under his sole and absolute rule. Anyone who got in his way — members of the deposed Chinese administration, stray Bolsheviks, anyone who could conceivably be Jewish — met with the kind of medieval cruelty of which Genghis himself would have approved. Tricked out in Mongolian costume (which reminded everyone else of a bright yellow dressing-gown), Ungern routinely flogged people to death, hanged lamas and did nothing to stop one of his soldiers indulging in his speciality of seizing old ladies off the street and choking them to death. Ungern’s earlier mental instability — fellow officers had wondered at his suicidal bravery on the battlefield during the eastern campaigns of the World War I — now blossomed into outright psychosis.

Palmer’s book is, in truth, probably one for the boys, or at least for people good at remembering who is fighting whom and why at any particular moment. If you’re not that way inclined, there are still plenty of “horrid history” moments to keep you enthralled — for instance, the fact that the baron’s men were great advocates of “the eternal boot,” whereby a soldier took the skin of a freshly killed animal, wrapped it around his foot and let it harden. Specialists will know that Ungern’s story has been told several times before, but newcomers will surely find it startling to learn that at least a decade before Hitler came to power, there was already a European leader whose adherence to a mix of sloppy religiosity, historical determinism and half-baked racialism was in danger of getting him far further than any sane person could possibly have predicted.

No one saw it coming. Everyone — including the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) — expected at least some of the recall campaigns against 24 of its lawmakers and Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安) to succeed. Underground gamblers reportedly expected between five and eight lawmakers to lose their jobs. All of this analysis made sense, but contained a fatal flaw. The record of the recall campaigns, the collapse of the KMT-led recalls, and polling data all pointed to enthusiastic high turnout in support of the recall campaigns, and that those against the recalls were unenthusiastic and far less likely to vote. That

Behind a car repair business on a nondescript Thai street are the cherished pets of a rising TikTok animal influencer: two lions and a 200-kilogram lion-tiger hybrid called “Big George.” Lion ownership is legal in Thailand, and Tharnuwarht Plengkemratch is an enthusiastic advocate, posting updates on his feline companions to nearly three million followers. “They’re playful and affectionate, just like dogs or cats,” he said from inside their cage complex at his home in the northern city of Chiang Mai. Thailand’s captive lion population has exploded in recent years, with nearly 500 registered in zoos, breeding farms, petting cafes and homes. Experts warn the

A couple of weeks ago the parties aligned with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), voted in the legislature to eliminate the subsidy that enables Taiwan Power Co (Taipower) to keep up with its burgeoning debt, and instead pay for universal cash handouts worth NT$10,000. The subsidy would have been NT$100 billion, while the cash handout had a budget of NT$235 billion. The bill mandates that the cash payments must be completed by Oct. 31 of this year. The changes were part of the overall NT$545 billion budget approved

The unexpected collapse of the recall campaigns is being viewed through many lenses, most of them skewed and self-absorbed. The international media unsurprisingly focuses on what they perceive as the message that Taiwanese voters were sending in the failure of the mass recall, especially to China, the US and to friendly Western nations. This made some sense prior to early last month. One of the main arguments used by recall campaigners for recalling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers was that they were too pro-China, and by extension not to be trusted with defending the nation. Also by extension, that argument could be