If only there were a photograph of soccer star George Best in London Tate Modern’s new Street & Studio show. Not one of him strutting his stuff on the pitch (the sporting equivalent of the street), but sitting in a studio — TV, I mean — retelling, for the umpteenth time, the story of how he was holed up at some luxury hotel in Monte Carlo or wherever. He’s in this suite of rooms with an open suitcase full of cash, Miss World is draped over the bed, the floor is littered with empty champagne bottles. There’s a knock on the door: room service delivering another magnum of vintage bubbly. The waiter takes everything in and asks wanly: “Mr Best, where did it all go wrong?”

Confronted by an intoxicating scene of enviable excess and success, the visitor to Street & Studio: An Urban History of Photography will surely identify with that waiter. To view the show not as a triumph but solely as a site of squandered opportunity is, however, to succumb to the false dichotomy suggested by its title: for this is triumph and waste simultaneously. Its ultimate failure is the inevitable culmination of a long history of victories and successes.

Let’s start, like the show, a long way back, in the last decade of the 19th century, with one of these early successes. Partly through a misunderstanding, partly through a desire to allay the suspicion that the mechanical medium of photography was more suited to scientific investigation or numb empirical recording than artistic creation, there developed the international movement known as pictorialism. As the name suggests, the idea was to make painterly photographs, images that had the subjective blur or atmospheric haze — another misunderstanding — of impressionism. With this aim, negatives and prints were physically worked on as though they were little canvases by photographers who — the hands-on approach proved it — were indeed artists.

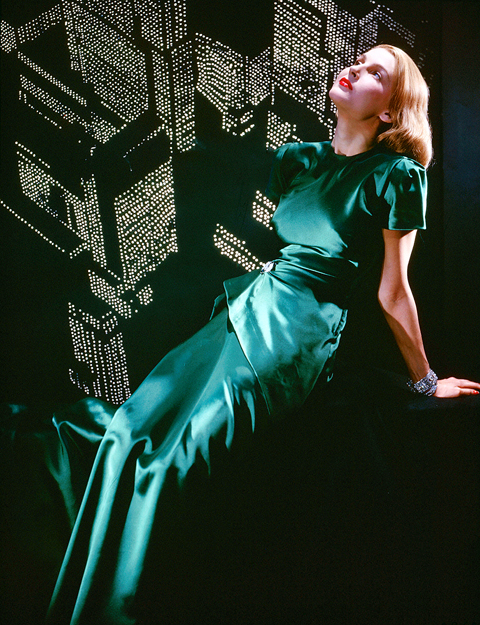

PHOTO COURTESY OF TATE MODERN

Few embraced this cause more enthusiastically than the young Alfred Stieglitz — and none was more active in its subsequent repudiation. Not just in his own work as a photographer, but as proselytizer, editor and gallerist, Stieglitz — together with his ally, the painter-photographer Edward Steichen — labored to establish pictorialism as the dominant form of photographic art in the US. By the end of the first decade of the new century, they had succeeded. As often happens, the moment of official institutional triumph — a retrospective exhibition in 1909 — was also an acknowledgment of creative exhaustion. Not that Stieglitz personally was tired (or, rather, he was one of those men for whom exhaustion was an incitement to further exertions): within a few years, he had shifted his matchless powers of persuasion and advocacy to promoting “straight” photography, especially as practiced by a young photographer who, under his tutelage, had become hostile to any residue of pictorial fuzziness and had achieved an “absolute, unqualified objectivity”.

In a sense, the twin strands of Street & Studio begin with the work made by Paul Strand around 1916: the quasi-abstract still lifes done on his porch (his studio, let’s say) and the photographs taken surreptitiously on the street. Speaking of the best-known of these, Blind Woman, Strand said that, although the picture had “enormous social meaning and impact, it grew out of a very clear desire to solve a problem.” That problem was how to photograph “people in the streets without their being aware of it”. (The problem these days, as Brooklyn-based street photographer Gus Powell recently explained, is that “it’s harder and harder to take a picture without somebody in the picture who’s also taking a picture”.)

The importance of Blind Woman in the subsequent history of American photography is hard to exaggerate. This was the picture that, by his own account, “charged up” the young Walker Evans and made him think, “That’s the thing to do.” Evans later devised his own method of taking pictures on the New York subway without people being aware of what he was up to. Combine Evans’ delicately unflinching gaze — a friend remarked that, when photographing slums, Evans kept his gloves on — with Henri Cartier-Bresson’s revelation of the fleeting poetry of the moment, and the ground is prepared for the exquisitely rendered, spontaneous choreography of the everyday revealed in Helen Levitt’s street scenes. In the mid-1950s, Evans’ protege, the Swiss Robert Frank, brought to the table an utterly unexpected quality: gruff indifference, both to the claims of human dignity by which earlier generations of documentary photographers — Strand among them — had set such store and to any received idea of how a photograph was supposed to look. Scramble all of this together and, by the late 1960s and early 1970s, the street, in the unharnessed — at times, it seems, unhinged — fecundity of Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, has become a giddy torrent of visual possibility.

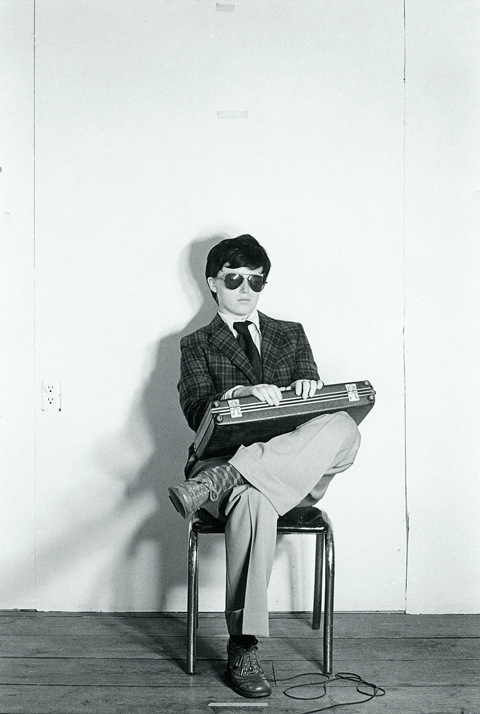

PHOTO COURTESY OF TATE MODERN

Friedlander and Winogrand were both studiously untheoretical, but the street, as revealed in their work, is at once a sprawling Balzacian novel, a fashion shoot and a walking sociological thesis. Notions of identity and selfhood — what Richard Sennett, in The Fall of Public Man, calls the “involuntary disclosure of character in public” and “isolation in the midst of visibility to others” — are hilariously, deliberately and accidentally investigated and discarded in frame after abundant frame. “There must be eyes on the street,” declared Jane Jacobs in The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), and a generation of photographers was on hand to see that her call was answered.

In comparison with the magnetic lure of the street, what could the measured seclusion of the studio have to offer? For Richard Avedon, it was not a place of contrivance or artifice, but a zone of elimination in which everything except the stark confrontation between camera and subject was rigorously excluded. At its most ruthlessly reductive, we are left with what Truman Capote — who had first-hand experience of Avedon’s working methods — called “the mere condition of a face.”

The Tate exhibition acknowledges that the distinction between street and studio is not absolute, that there is a continuous traffic between the two. For some photographers, the street is the studio. In the mid-1990s, Philip-Lorca diCorcia chose propitious-seeming spots in New York and elsewhere and then, when the moment came, did not simply press the shutter, but activated a whole series of lights that isolated the unwitting subject in a filmic aura of radiant illumination.

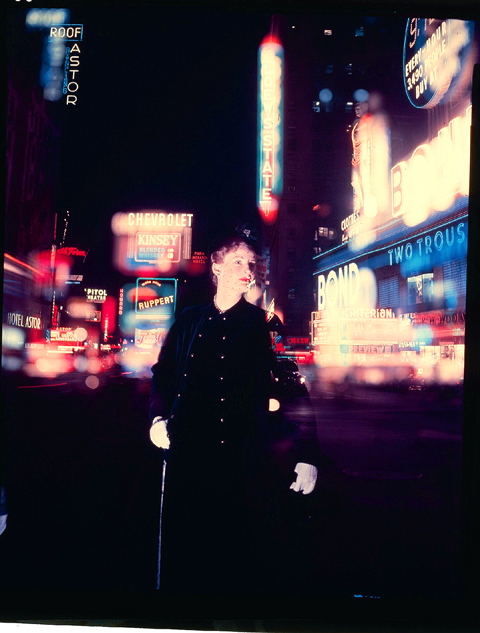

PHOTO COURTESY OF TATE MODERN

Less technically demanding, the best-known example of street-as-studio work must be Ruth Orkin’s 1951 shot (not at the Tate, strangely) of an attractive American woman in Florence, running a multi-generational gauntlet of lounging men, who howl their salacious appreciation from street corner, cafe tables and Vespa. It’s a witty and stylish photograph — and Orkin has never made any secret of how it was achieved. Together with a young art student she had met, the photographer told the guy on the Vespa what she had in mind and he explained it to his friends who gamely joined in. Does the fact that everyone in the picture is acting make it a fake? Not really: the street, in Italy, is an outdoor stage on which the ongoing tragicomedy of being Italian is acted out in perpetuity.

But remember, this is just one picture; in the larger scheme of things Winogrand was right to insist that, while he had nothing against set-ups, he could never dream up anything to match the swirling circus that was enacted, unsolicited, before his voracious eye, every hour of every day.

Winogrand was one of the photographers enthusiastically championed by John Szarkowski who, in 1962, took over from Steichen as head of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The photographic landscape as we know it today is still recognizably the one determined by Szarkowski’s curatorial and critical ambitions. A plethora of benchmark exhibitions and initiatives included the Evans retrospective of 1971 and the acquisition, from Berenice Abbot, of the Eugene Atget archive in 1968. It was Abbot who had introduced Evans to Atget’s work in 1930, and the effect on him was as powerful as his earlier exposure to Strand. If he had reacted strongly against Stieglitz as a “screaming aesthete,” he was drawn to Atget — who, far from calling himself an artist, created pictures to be sold as “Documents for Artists” — for precisely the opposite reasons. Compiled, principally, in the first quarter of the 20th century, Atget’s lyrical taxonomy of “old Paris” prefigured and informed Evans’ own comprehensive documenting of the social landscape of America. In the introduction to the catalogue accompanying the 1971 retrospective, Szarkowski presented Evans’s achievement in a way that tacitly twinned him with Atget. And not only that. In Szarkowski’s terms, Evans and Atget become virtually synonymous with the historic venture and mission of photography itself.

PHOTO COURTESY OF TATE MODERN

Szarkowski’s notion of what constituted “significant fact” was both fiercely discerning and radically democratized. Long considered incompatible with real seriousness — Evans thought it “vulgar” — color photography was suddenly granted institutional acceptance with the exhibition, in 1976, of work by William Eggleston. That paradigm-shifting moment helped establish the conditions for the current deluge of color work. (Much contemporary color photography is on a vast scale; Szarkowski was traditionalist enough to believe that most prints did not need to be bigger than 24 inches by 20, pretty titchy by today’s standards.)

Photography’s gradual establishment in the museum went hand in hand with the emergence of a buoyant market for shows and sales in private galleries. This two-pronged expansion coincided with a decline in the opportunities for commissions by magazines. In the early 1930s, Robert Capa had advised Cartier-Bresson to call himself not a surrealist or an artist, but “a photojournalist and then do whatever you like.” Fifty years later, the situation was poised to be reversed: photographers would now operate within a branch — and under the demands — of the fine art market. What we see now, in museums, art fairs and galleries, is a logical if delirious flourishing of that hard-won success.

In the setting of our Tate Modern, one can perhaps see a pattern emerging in the way photography is currently presented. Five years ago there was the exhibition Cruel and Tender; now we have Street & Studio: twin pairs of antinomies so vast as to embrace anything and everything. What next? Little and Large (from Kertesz to Gursky)? Heaven and Earth? Under such generous awnings and rubrics, the curator can scarcely go wrong.

PHOTO COURTESY OF TATE MODERN

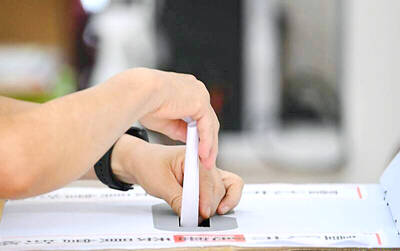

No one saw it coming. Everyone — including the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) — expected at least some of the recall campaigns against 24 of its lawmakers and Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安) to succeed. Underground gamblers reportedly expected between five and eight lawmakers to lose their jobs. All of this analysis made sense, but contained a fatal flaw. The record of the recall campaigns, the collapse of the KMT-led recalls, and polling data all pointed to enthusiastic high turnout in support of the recall campaigns, and that those against the recalls were unenthusiastic and far less likely to vote. That

Behind a car repair business on a nondescript Thai street are the cherished pets of a rising TikTok animal influencer: two lions and a 200-kilogram lion-tiger hybrid called “Big George.” Lion ownership is legal in Thailand, and Tharnuwarht Plengkemratch is an enthusiastic advocate, posting updates on his feline companions to nearly three million followers. “They’re playful and affectionate, just like dogs or cats,” he said from inside their cage complex at his home in the northern city of Chiang Mai. Thailand’s captive lion population has exploded in recent years, with nearly 500 registered in zoos, breeding farms, petting cafes and homes. Experts warn the

A couple of weeks ago the parties aligned with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), voted in the legislature to eliminate the subsidy that enables Taiwan Power Co (Taipower) to keep up with its burgeoning debt, and instead pay for universal cash handouts worth NT$10,000. The subsidy would have been NT$100 billion, while the cash handout had a budget of NT$235 billion. The bill mandates that the cash payments must be completed by Oct. 31 of this year. The changes were part of the overall NT$545 billion budget approved

Before performing last Friday at Asia’s bellwether music festival, Fuji Rock in Japan, the Taiwanese indie band Sunset Rollercoaster (落日飛車) had previously performed on one of the festival’s smaller stages and also at Coachella, the biggest brand name in US music festivals. But this set on Fuji Rock’s main stage was a true raising of the bar. On a brilliant summer’s evening, with the sun rays streaming down over a backdrop of green mountains and fluffy white clouds, the performance saw the Taiwanese groovemasters team up with South Korean group Hyukoh, with whom they’ve formed a temporary supergroup called AAA