Evil is not a primary color. That is the point of the Wachowski brothers’ video-arcade treatment of Speed Racer, insofar as one can be determined. Blue, you can trust. Red and yellow, black and white — they’re all decent visible wavelengths. It’s purple you have to watch out for.

This is notable only because whatever information that passes from your retinas to your brain during Speed Racer is conveyed through optical design and not so much through more traditional devices such as dialogue, narrative, performance or characterization. Like the animated TV series that inspired this movie, you could look at it with the sound off and it wouldn’t matter.

Speed Racer is not a feature film in any conventional sense — although there is nothing so conventional in today’s marketplace as a corporate product based on a campy vintage TV show that is developed for extremely brief exhibition in multiplexes on its way to more appropriate platforms such as DVD and video games, which provide the principal justification for its manufacture in the first place.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF WARNER BROS

Neither is Speed Racer a commercial avant-garde film (though fans of the Wachowski brothers may wish to make such claims), unless you still consider Laserium shows of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon to be cutting edge. (Lights! Shapes! Colors! Motion! Money!) And there’s nothing terribly adventurous these days about Eisensteinian montage treated as if it were William Burroughs’ “cut up” technique — with digital clips randomly scrambled like pixelated confetti.

Nor is it some kind of subversive commodity, unless the outre strategy of pandering to a low-brow, retro-nostalgic crowd can be considered anything but business as usual in 2008. The faux naivete on display here — right down to the imitation-fruit-flavored FDA-food-dye coloring — is both shamelessly quaint and shamelessly cynical.

For a certain generation of American kids, Speed Racer was our introduction to the lo-fi animated form now known as anime. At the time, we just thought it was cheapo Japanese animation: flat, static, dubbed into badly translated English and barely “animated” at all, given that the frame only seemed to change approximately two times per second and the “moving” backgrounds were made up of about four cyclically repeating drawings instead of the eight or so we were used to seeing in Hanna-Barbera cartoons. The faster Speed went, the slower the sequence of backgrounds. Wow.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF WARNER BROS

To us, this show was just filler between after-school reruns of Gilligan’s Island and The Munsters. We watched it because it was on, and it was in color.

Now the Wachowski brothers (of the Matrix movies) have spent US$100 million on a mixture of photography and digital animation and called it Speed Racer. They have captured (almost) all the chintziness, inexpressiveness and incoherence of the TV show in two hours and nine minutes, or about two hours too long, give or take. Yet some of us would just rather re-rent Tron (1982), which was not only a more immersive, dimensional and original take on the Commodore 64 video-graphics aesthetic, but also funnier and more exciting.

The live-action components of Speed Racer include Speed himself (Emile Hirsch, consigned to anonymity again after a breakout performance in Into the Wild), who lives with his mom (Susan Sarandon), pops (John Goodman), mischievous little brother Spritle (Paulie Litt), pet chimp Chim-Chim (Kenzie and Willy) — as well as, apparently, his mechanic Sparky (Kick Gurry) and his gal-pal Trixie (Christina Ricci). They all love Mom’s pancakes.

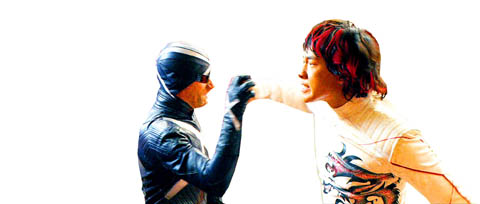

Speed once idolized his big brother Rex Racer (Scott Porter), who died in a fiery car crash as idolized big brothers named “Racer” will sometimes do. Rich, evil, purple-clad industrialist Royalton (Roger Allam, as Tim Curry) woos Speed with a lucrative offer, but when the hotshot turns it down in favor of sticking with Pops, Royalton threatens to destroy all Racers. Fortunately, the mysterious Racer X (Matthew Fox, displaying fewer emotions than Jack on Lost) zips in to help out.

As an elementary schooler, Speed is afflicted with foot-tapping hyperactivity and ADD, and so is the movie. A lot of fluorescent, 7-Eleven-tinted images flash by, any of which could easily be removed or re-arranged without significantly disrupting the film’s continuity, because it has none. If you can determine the spatial relationship between Speed’s Mach 5 (or Mach 6) and any other race car for more than a few consecutive seconds, then good for you. As on the TV series, the pictures don’t seem to move so much as repeat — movement with no momentum. Transitions are handled with wipes in which large closeups pass from one side of the screen to the other without ever getting anyone anywhere.

If non-pixel illumination was used in the (mostly green-screen) shooting of the movie at all, it appears to have been black light, which gives everything a phosphorescent, psychedelic-poster sheen. At various times, the visuals resemble Blade Runner reinterpreted by Roger Dean (of Yes album cover fame), The Jetsons designed by Maxfield Parrish, or a bag of Skittles designed by Shag.

Speed Racer is a manufactured widget, a packaged commodity that capitalizes on an anthropomorphized cartoon of Capitalist Evil in order to sell itself and its ancillary products. Corporate partners in the venture include General Mills, McDonald’s, Mattel, Topps, LEGO and Target, who have furnished no promotional consideration for mention in this review.

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

At Computex 2025, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) urged the government to subsidize AI. “All schools in Taiwan must integrate AI into their curricula,” he declared. A few months earlier, he said, “If I were a student today, I’d immediately start using tools like ChatGPT, Gemini Pro and Grok to learn, write and accelerate my thinking.” Huang sees the AI-bullet train leaving the station. And as one of its drivers, he’s worried about youth not getting on board — bad for their careers, and bad for his workforce. As a semiconductor supply-chain powerhouse and AI hub wannabe, Taiwan is seeing

Jade Mountain (玉山) — Taiwan’s highest peak — is the ultimate goal for those attempting a through-hike of the Mountains to Sea National Greenway (山海圳國家綠道), and that’s precisely where we’re headed in this final installment of a quartet of articles covering the Greenway. Picking up the trail at the Tsou tribal villages of Dabang and Tefuye, it’s worth stocking up on provisions before setting off, since — aside from the scant offerings available on the mountain’s Dongpu Lodge (東埔山莊) and Paiyun Lodge’s (排雲山莊) meal service — there’s nowhere to get food from here on out. TEFUYE HISTORIC TRAIL The journey recommences with