Tomas Maier cultivates tenacity. If a tree in his garden doesn't thrive, he simply uproots it and replants. If a supermarket tomato is not tangy enough for his taste, he is apt to grow his own. "People like myself cannot get happy," Maier mused last week as he sat in the courtyard below one of his namesake stores in Palm Beach, Florida. "I'm always looking for something that is not there."

During a fashion career spanning more than two decades, Maier channeled this pursuit of an elusive perfection into designs so low-key and finely tuned that they often flew beneath the radar. Then a half-dozen years ago, he trained his sights on Bottega Veneta, transforming that once-ailing fashion house into one of Europe's top-selling luxury brands, with annual sales of more than US$500 million worldwide.

Today the muted logo-free look that is the brand's signature is widely regarded as the standard-bearer for a new kind of luxury: subtle, long-lasting and recession-proof. In such a climate, Maier himself has emerged as a hero, albeit a reluctant one - and, to his admirers, even something of a prophet.

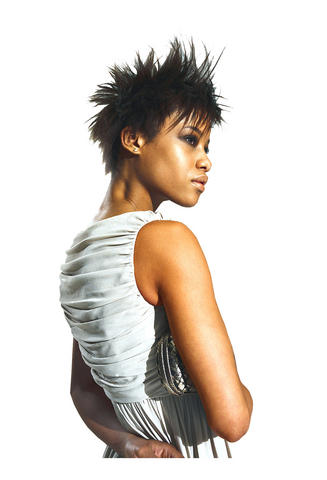

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

"He's not one of those in-one-season-out-another people," said Julie Gilhart, the fashion director of Barneys New York, which carries Bottega Veneta dresses and accessories. "The fashion business has so much of that - so much marketing, so much hype - that there needs to be a spot where that doesn't exist. He's definitely the person who has created that spot."

If he did, it was by cutting against the grain. While competitors were churning out look-alike handbags made of coated canvas, bearing hefty hardware and equally hefty price tags, Maier perfected his specialty: the Intrecciato series of hand-woven bags, some that take two days of labor to make (compared with about 80 minutes for a standard-issue designer bag). Signature products, devoid of initials, they typically sell for US$1,200 to as much as US$4,500.

While other designers were producing dart-free baby-doll dresses as if they were so many Fords, he concentrated on deceptively simple, painstakingly constructed styles priced from about US$1,200 to US$6,000 for an evening dress. The dressmaker touches - ruching, serpentine seaming, hand-beading and elaborate pleats - are recognizable to a small but informed clientele.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

His maverick approach has reaped rewards. Bottega Veneta has become the second-highest earner at the Gucci Group, under its owner, PPR, which took control of the brand in 1999. Its clothing and accessories are distributed at upscale stores like Saks Fifth Avenue and Neiman Marcus, as well as at more than 100 Bottega Veneta shops from Moscow to Mumbai.

The Cabat, a sort of woven leather shopping bag that is one of Maier's earliest designs, remains in the line, evolving almost imperceptibly from season to season. Even with a stratospheric price tag of as much as US$6,000, it continues to attract a following.

To be sure, that following was slow to build. Critics often overlooked Bottega Veneta, and shoppers turned to showier pieces. But Maier, 51, persisted, imposing his iconoclastic vision on the house.

From the outset, Maier drew a cult by catering to the type of woman who may buy only one new bag a year - if that. "She will ask herself, 'Do I really need all this stuff that's disposable?'" he said, adding ringingly, "The answer is no."

That statement is heresy, he knows. "When I started to talk like this, people thought I was nuts."

But fashion has caught up with Maier, whose subtle aesthetic and considered approach to design speak to a powerful niche.

Faced with a recession, affluent consumers "don't want to be screaming luxury right now," said Milton Pedraza, the chief executive of the Luxury Institute, a research group in New York. "They don't want something flashy that everybody else has. They are looking for unique handcrafted things that can't immediately be reinterpreted at every level of the marketplace."

A consumer survey by the Luxury Institute last year lent substance to that observation. Respondents, Pedraza said, placed Bottega Veneta in the first tier of luxury brands, ranking with Hermes and Vera Wang among the top three in consumer recognition and approval.

Those consumers are shopping for "sustainable luxury," said Ed Burstell, a senior vice president at Bergdorf Goodman. Instead of buying a US$1,500 handbag that may be indistinguishable from versions selling for one tenth of the price, they may part with several thousand US dollars for a piece that looks durable and worth the splurge. Yes, those shoppers represent a minute portion of the population, but their devotion has helped build the brand. The leather goods account for 82.3 percent of the company's sales.

Those values are in keeping with the original aims of the house. In the mid-1960s, Bottega Veneta was among a handful of small leather-goods makers setting the standard for Italian craftsmanship. In the 1970s, its intricately woven rustic-looking designs were sufficiently identifiable to inspire the company's slogan, "When your own initials are enough."

But by 2001, when the Gucci Group bought the brand for roughly US$200 million, its standards had eroded. The company was bankrupt, said Domenico de Sole, Gucci's former chief, its 21 stores selling flashy but otherwise unmemorable leather goods. That year Tom Ford, then the creative director of the Gucci Group, hired Maier, who had designed for Hermes and Sonia Rykiel, to restore the luster of the brand.

"It was probably one of the worst moments in the economy," Patrizio Di Marco, the president of Bottega Veneta, recalled. The post-9/11 recession "injured an industry that is usually resistant to economic downturns," he said.

Despite the sagging market, Maier stuck to his ways. With the blessing of Ford and De Sole, he ignored a few cherished marketing precepts, refusing, for instance, to follow the widespread practice of turning out a successful bag in three sizes and adjusting the prices accordingly. "If the bag is right, one version is enough," Maier insists to this day.

At other companies, where the creative director holds less sway, he might have been out in a season, De Sole said.

Conscientious almost to a fault, Maier will not make pieces that are strictly for show. "I never design for design's sake," he said. "You don't put things on the runway and then not sell them at the store. Women hate that."

Unlike high-end competitors, many of whom manufacture in China, the company under his direction continues to makes bags, clothing and jewelry in Italy. A furniture collection is also manufactured in Europe.

At times Maier encountered opposition. Andrew Preston, his companion of 20 years and a partner in the two Tomas Maier stores, acknowledged that the designer had to overcome a certain amount of skepticism. "He doesn't believe in the quick fix and the gimmick product," Preston said. "People in fashion found that a bit odd, because this is a disposable business, generally."

Looking back on his career, Maier prides himself on taking the long view. "I've always been such an outsider," said the designer, the son of a successful architect in Germany. Growing up in the small town of Pforzheim, in the Black Forest, he sat at his father's drafting table and accompanied him to building sites, evolving an eye for line and form, and learning patience.

A degree of asceticism informs his work and even extends to the clothes he wears, monochromatic ensembles, many of his own design. A reluctant pinup, Maier cultivates a monkish look, his hair close-cropped, his chin stubbled, his lips compressed. And like a proper friar, he shuns the limelight.

You will not find him out partying with the Beckhams or recovering from his excesses at some boutique rehab. When he is not in Italy monitoring production, he is minding the Tomas Maier stores, the first in Miami Beach and the latest in Palm Beach, which opened in November. At other times he can be seen taking a spade to his flower beds, often as early as 6am.

Sure, he allowed, fashion thrives on a star system, catapulting last season's unknown into the celebrity stratosphere, "and then, who knows … "He trailed off, then brightened. "I don't think you need to be like that," he said. "In any case, I don't want it."

Is his demurral self-protective? "People are very fickle," Maier said. A canny glint in his eye, he added, "If you're never in fashion, you are never out."

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

In an interview posted online by United Daily News (UDN) on May 26, current Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) was asked about Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) replacing him as party chair. Though not yet officially running, by the customs of Taiwan politics, Lu has been signalling she is both running for party chair and to be the party’s 2028 presidential candidate. She told an international media outlet that she was considering a run. She also gave a speech in Keelung on national priorities and foreign affairs. For details, see the May 23 edition of this column,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

At Computex 2025, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) urged the government to subsidize AI. “All schools in Taiwan must integrate AI into their curricula,” he declared. A few months earlier, he said, “If I were a student today, I’d immediately start using tools like ChatGPT, Gemini Pro and Grok to learn, write and accelerate my thinking.” Huang sees the AI-bullet train leaving the station. And as one of its drivers, he’s worried about youth not getting on board — bad for their careers, and bad for his workforce. As a semiconductor supply-chain powerhouse and AI hub wannabe, Taiwan is seeing