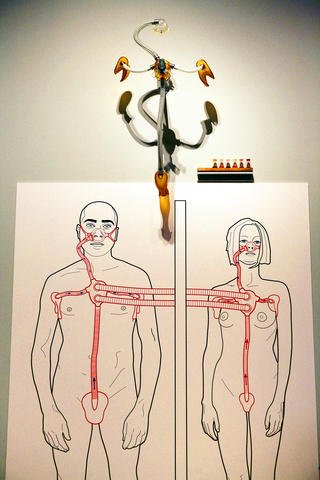

In the drawing, a nude man and woman stand on either side of a wall. Each wears a plastic breathing mask that covers the nose and mouth; the masks are connected to air hoses that pass through the wall. The hoses attach to pouches at each other's underarms and crotches.

It's a device that allows people to sniff each other. Remotely.

Things can get weird when the worlds of science and design collide. A new exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Design and the Elastic Mind, contains more than 200 arresting and provocative objects and images that may evoke a "whoa" or an "ugh" or simply "huh?"

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

When art museums take on science, the results are often pretty but superficial, with blown-up images from under a microscope or through a telescope and artificial colors, said Peter Galison, a Harvard professor of the history of science and of physics. He said this "out-of-context aestheticization" was not just "kitschy," but could also kill the depth and context that made science interesting.

Design and the Elastic Mind, Galison said approvingly, is different - playful, yet respectful of the science that informs each object on display. "It's science in a new key," he said.

In this exhibition, Paola Antonelli, senior curator in the museum's department of architecture and design, gathered the work of designers and scientists, meeting in the sweet spot on a cultural Venn diagram where the two disciplines overlap.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

The exhibition came together through an unusual process, Antonelli said. Some two years ago, she began talking with Adam Bly, the editor of a hip science magazine, Seed, and asked him to collaborate with her on a series of salons devoted to exploring the relationship between science and design.

"At the beginning it was this sort of apology-fest," Antonelli said. She recalled the way scientists would open their talks by saying, "I don't know what art is," and the artists would say they did not know any formulas. Through the salons - with speakers like Benoit Mandelbrot, a mathematician who pioneered the creation of gorgeous images from mathematical functions, and leading designers - the outlines of an exhibition took form.

The works that come from laboratories have a quality that can evoke wonder: a soft-bodied robot designed to move like a caterpillar, and movies of a circular pool with wave-generation machines ringed around it that beat the water in rhythms and that can form letters of the alphabet. And, yes, some images come from under microscopes. But they stay true to their scientific roots, said Paul Rothemund, a scientist at Caltech, whose work is on display. He manipulated molecules of DNA to create a series of microscopic smiley faces that are one one-thousandth the width of a human hair.

"The work isn't mere artwork," he wrote in an e-mail message in response to questions. "Artwork is necessary for engineering and science."

The designers tend to approach the work with a bit more puckishness. There are visual displays of data that present, for example, thousands of personal advertisements in a heart-shaped flux of bubbles that can be searched and manipulated. And there are the smell tubes. The designer of the Smell (PLUS) project, James Auger, said he wanted to underscore the diminished importance the sense of smell had in our lives by creating a device that allowed people to smell each other's bodily scents before they met. It would be a kind of olfactory blind-dating service.

Is it a serious proposal? Auger, who is from Britain, hedges. The science of smell, he notes, is serious, and he cites research into smell as a marker for genetic compatibility. He said he was fascinated by science and scientists, who were "creating amazing possibilities of what it means to be human. But they don't necessarily understand what to be human is. That's where design can play a very important role."

So while scientists have studied the ways that smell might have developed to warn humans of food gone bad or an approaching fire, it is up to designers to encourage people to think about what is lost when we have "fire alarms and sell-by dates and fridges" and, for that matter, deodorants and perfume.

Other projects try to build by nature's plan. Joris Laarman, a designer in the Netherlands, is designing chairs and sofas based on his research into the way that bone grows - giving support where needed and removing material where less support is required. A result is an eerily elegant assortment of legs that form a whole, using software that mimics evolutionary processes. "I try to create beautiful objects that make sense," Laarman said.

And what can we make of the display of "dressing the meat of tomorrow"? It is a fanciful representation of what meat might look like when tissues for food can be cultivated cheaply in vats instead of through grazing and slaughtering. Practical applications that would bring the cost of "cruelty-free" tissue down to affordable prices are years away, at best.

But James King, a British designer who created the prototype for the brave new meat, said edible tissues from the lab opened possibilities for what cultured meat might look like. "It's not designed by the anatomy of the animal," King said. Instead of slabs of steak, he envisions a delicate design that resembles "the cross section of a cow."

Some of the objects have an otherworldly beauty. Tomas Gabzdil Libertiny, who lives in the Netherlands, studied bees and developed scaffolding he could use to enlist them in the manufacture of objects. His beeswax vase, a golden wonder that droops slightly on a pedestal near the entrance to the exhibition, exemplifies what he calls "slow prototyping." Like the "slow food" movement, he sees his vase as showing the way to a kind of thing that demands attention and respect, in part because it is not just knocked out by a machine - it embodies, he said, "the sort of thrill in the heart that you get when you see an object that has magic."

Mandelbrot, a professor emeritus of mathematical science at Yale, spoke with joy in an interview about the new exhibition, but also with an air that suggested he was wondering why it had taken so long for the world to catch up to him. "I have been fighting on that front for a very long time," he said.

Mandelbrot said the separation of science and aesthetics had always puzzled and frustrated him, though now "the separation is decreasing, or vanishing," as more people find ways to bridge the gap.

Bly, of Seed, agreed. Bringing diverse disciplines together corrects a mistake in intellectual history and "harks back to the Renaissance," he said, adding: "We created disciplines. Nature didn't create disciplines.

From the last quarter of 2001, research shows that real housing prices nearly tripled (before a 2012 law to enforce housing price registration, researchers tracked a few large real estate firms to estimate housing price behavior). Incomes have not kept pace, though this has not yet led to defaults. Instead, an increasing chunk of household income goes to mortgage payments. This suggests that even if incomes grow, the mortgage squeeze will still make voters feel like their paychecks won’t stretch to cover expenses. The housing price rises in the last two decades are now driving higher rents. The rental market

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

Fifty-five years ago, a .25-caliber Beretta fired in the revolving door of New York’s Plaza Hotel set Taiwan on an unexpected path to democracy. As Chinese military incursions intensify today, a new documentary, When the Spring Rain Falls (春雨424), revisits that 1970 assassination attempt on then-vice premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國). Director Sylvia Feng (馮賢賢) raises the question Taiwan faces under existential threat: “How do we safeguard our fragile democracy and precious freedom?” ASSASSINATION After its retreat to Taiwan in 1949, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regime under Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) imposed a ruthless military rule, crushing democratic aspirations and kidnapping dissidents from

Fundamentally, this Saturday’s recall vote on 24 Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers is a democratic battle of wills between hardcore supporters of Taiwan sovereignty and the KMT incumbents’ core supporters. The recall campaigners have a key asset: clarity of purpose. Stripped to the core, their mission is to defend Taiwan’s sovereignty and democracy from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). They understand a basic truth, the CCP is — in their own words — at war with Taiwan and Western democracies. Their “unrestricted warfare” campaign to undermine and destroy Taiwan from within is explicit, while simultaneously conducting rehearsals almost daily for invasion,