Thirty-three years ago museum librarian Teng Shu-ping (鄧淑蘋) stumbled across cases of jade carvings with distinct Islamic motifs in the National Palace Museum's (NPM) massive repository. After years of study and research aided by colleagues in the UK, China, India, Turkey and the US, Teng - now head of the antiquity department and program curator - has shed new light on the artwork and revised the museum's original 1982 Islamic jade exhibition.

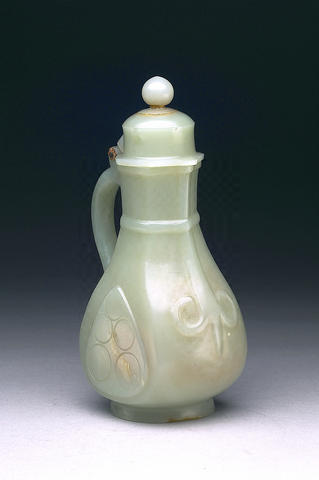

Showing more than 140 Islamic jades and some 20 counterfeits made by Chinese and Uighur craftsmen during the 18th century, the exhibition traces the history and development of jade-making. Some pieces date as far back as the 14th-century Ottoman Empire, others come from the Timurid Empire in Central Asia (1370-1506) and the Mughal Empire (1526-1857) in Southern Asia.

The primary material is nephrite jade from the Kunlun mountains and the Khotan region of Central Asia. The craftsmanship on the steppe was recorded in ancient documents dating back to the early 15th century. The jade vessels on display are plain with thick walls and an indentation on the bottom, which differs from the even-bottomed Chinese versions.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF NPM

When the Timurid Empire collapsed in the early 16th century, descendants of the imperial line invaded India to found the Mughal Empire and took with them the jade-carving tradition. The Islamic jade art peaked during the 17th century when Emperor Jahangir and his son, Shah Jahan (builder of the Taj Mahal) were enthusiasts for the art form and recruited artisans from Europe and Persia to serve at the court.

The melding of Central Asian tradition with designs and techniques from China, India and Europe gave birth to what has come to be known as the classical Mughal jades. Plants, fruits and floral ornaments from this period demonstrate remarkable artistry.

"Any art needs to take in innovations in order to inspire and the Mughal jade carvings serve as a good example of the constant process of revitalization," Teng said.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF NPM

Teng suggested that a distinction be made between classical Mughal jades and non-classical Mughal-style Indian jades. She further contributed to the field by identifying the latter as pieces produced in regions, such as the Deccan Plateau, beyond the control of the Mughal Empire. Such pieces are smaller, single handled and have a distinct Hindu flavor combined with Turkish and Chinese influences.

The Turkish people in Central Asia eventually migrated to Western Asia and Eastern Europe and established the Ottoman Empire. The jade-carving tradition there was less developed and fewer jade articles were used in the West than in the South. This is due, in part, to the regions' distance from jade mines. The items from this era illustrate the unique features of Ottoman jade, which is defined by symmetrical and stylized floral motifs, almost transparent thin walls and the shallow scooping technique that created rounded or oval indentations.

The eastward journey of the Islamic jades began when Emperor Qianlong (乾隆) of the Qing Dynasty (1736-1796) first laid eyes on the delicate treasures sent to him as tribute. Fascinated by the intricate art form, he imported many examples to Xinjiang from Turkey and India, then onto Beijing. In the meantime, workshops in Southern China started producing counterfeits to meet increasing demand.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF NPM

Unaware of the existence of Turkish jades and Chinese forgeries sent along with the genuine pieces from Xinjiang, Qianlong named his accumulation of Islamic treasures the Hindustan Jades, part of which has long been in the NPM's collection.

For those interested in knowing more about the Islamic jades, a bilingual book containing illustrations and detailed research will be available in the museum's gift shop by the end of this month.

May 11 to May 18 The original Taichung Railway Station was long thought to have been completely razed. Opening on May 15, 1905, the one-story wooden structure soon outgrew its purpose and was replaced in 1917 by a grandiose, Western-style station. During construction on the third-generation station in 2017, workers discovered the service pit for the original station’s locomotive depot. A year later, a small wooden building on site was determined by historians to be the first stationmaster’s office, built around 1908. With these findings, the Taichung Railway Station Cultural Park now boasts that it has

Wooden houses wedged between concrete, crumbling brick facades with roofs gaping to the sky, and tiled art deco buildings down narrow alleyways: Taichung Central District’s (中區) aging architecture reveals both the allure and reality of the old downtown. From Indigenous settlement to capital under Qing Dynasty rule through to Japanese colonization, Taichung’s Central District holds a long and layered history. The bygone beauty of its streets once earned it the nickname “Little Kyoto.” Since the late eighties, however, the shifting of economic and government centers westward signaled a gradual decline in the area’s evolving fortunes. With the regeneration of the once

In February of this year the Taipei Times reported on the visit of Lienchiang County Commissioner Wang Chung-ming (王忠銘) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a delegation to a lantern festival in Fuzhou’s Mawei District in Fujian Province. “Today, Mawei and Matsu jointly marked the lantern festival,” Wang was quoted as saying, adding that both sides “being of one people,” is a cause for joy. Wang was passing around a common claim of officials of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the PRC’s allies and supporters in Taiwan — KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party — and elsewhere: Taiwan and

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he