It was not the most eloquent line uttered in movie history, and it may have been one of the silliest: "Greetings, my friend. We are all interested in the future, for that is where you and I are going to spend the rest of our lives."

But the sentiment, as intoned by the celebrity psychic Criswell at the beginning of the 1959 astro-disaster Plan Nine From Outer Space, was a perfect way to explain the influence that the space race, then in its infancy, was already beginning to exercise on American popular culture and art - from movies and television to architecture and design.

An effect was much more than simply a spillover from the silvery streamlining of the space program. It was an increasing preoccupation with the future and technology that helped change not only the country's look in the 1950s and 1960s, but also, in some ways, its very conception of itself, as if seen anew from space.

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

The architect Buckminster Fuller, one of the space age's most ardent proselytizers, put it much more coherently in his book Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth: "We are all astronauts."

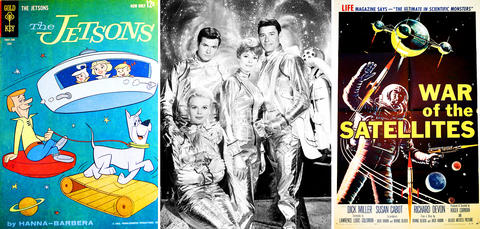

Deciding which cultural offerings from those post-Sputnik years were deep and lasting and which were probably not (space-age bachelor-pad music? The Jetsons? Barbarella? Tang?) would always be topics of impassioned debate among space aficionados. But a half-century into that once-imagined orbital future, it has become a little easier to put the era into cultural perspective.

The worlds of fashion, furniture, comic books and children's toys were all profoundly affected, often for the good.

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Television and the movies, as evidenced by examples like Plan Nine, Lost in Space and Invasion of the Saucer Men, in which an alien's severed hand crawled around wreaking havoc on the big screen, did not fare quite as well.

Even so, it is difficult to imagine cinema without Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. And it is almost impossible to imagine that movie, made in 1968, looking the way it did in the absence of an American space program, even with earlier influences like the spacey designer Raymond Loewy or the architect Eero Saarinen, whose curvy 1948 Womb chair looks like something made specially for Kubrick's set.

In the realm of art, the influence was smaller and, usually, less direct. The cultural scholar Dave Hickey said he always felt that the "ice-white cube," which became the standard kind of ascetic interior in museums and galleries by the 1960s, could be traced in part right back to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

"I remember thinking at the time that, all of a sudden, we were looking at art in clean rooms like those where the astronauts suit up," Hickey, a professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, said in a recent interview.

Robert Rauschenberg was probably the most famous artist to use space imagery front and center, incorporating pictures of astronauts and space capsules into his works in the 1960s.

At Bell Laboratories, which was intimately tied up with NASA in its earliest years, Billy Kluver, an engineer, organized groundbreaking collaborations with artists, including Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol, to inject space-age technology into artworks, a program whose legacy is still felt today.

Many cultural critics say probably the biggest impact can be seen in architecture. Especially in California and elsewhere in the West, the work of architects like John Lautner transformed the look of cities and highways with upswept wing-like roofs, domes, satellite shapes and starbursts that became the dominant visual language of motels, diners and gasoline stations.

Hickey describes the look as "somewhere between Hindu temples and launching pads."

The look, sometimes called Googie, after Lautner's design for the Googie's coffee shop in Los Angeles, predated the Sputnik launching and had influences back to Wayne McAllister's curvaceous hotels and drive-ins, to Frank Lloyd Wright and even to Futurism in the 1920s. It took off along with the space race and produced buildings that tried very hard to bring the Jetsons to life, like Lautner's 1960 Chemosphere, a saucer-shaped house that looks as if it is preparing to hover out over the Hollywood Hills.

Kenneth Frampton, the architectural historian, said it was often difficult to disentangle the threads of the space-age look, whose origins come from early airplane and jet design. Frampton added that the lines of influence that began with Fuller's geodesic domes and other futuristic ideas could be traced across the ocean to Archigram, the visionary group of British architects who proposed far-out projects (never realized) like capsule-shaped living pods and suits that could expand and double as structures.

Their spirit has, in turn, inspired and animated many contemporary high-tech architects like Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid and Renzo Piano, whose tubular, machinelike Pompidou Center, built with Richard Rogers, seems to evoke the space race in very specific ways.

"You could draw certain parallels between the structure of the Pompidou and the structure of the rocket-launching facilities at Cape Canaveral," said Frampton, who teaches at Columbia. "They might not have been thinking about it, but I think there is some kind of unconscious affinity there."

The unexpected collapse of the recall campaigns is being viewed through many lenses, most of them skewed and self-absorbed. The international media unsurprisingly focuses on what they perceive as the message that Taiwanese voters were sending in the failure of the mass recall, especially to China, the US and to friendly Western nations. This made some sense prior to early last month. One of the main arguments used by recall campaigners for recalling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers was that they were too pro-China, and by extension not to be trusted with defending the nation. Also by extension, that argument could be

Aug. 4 to Aug. 10 When Coca-Cola finally pushed its way into Taiwan’s market in 1968, it allegedly vowed to wipe out its major domestic rival Hey Song within five years. But Hey Song, which began as a manual operation in a family cow shed in 1925, had proven its resilience, surviving numerous setbacks — including the loss of autonomy and nearly all its assets due to the Japanese colonial government’s wartime economic policy. By the 1960s, Hey Song had risen to the top of Taiwan’s beverage industry. This success was driven not only by president Chang Wen-chi’s

Last week, on the heels of the recall election that turned out so badly for Taiwan, came the news that US President Donald Trump had blocked the transit of President William Lai (賴清德) through the US on his way to Latin America. A few days later the international media reported that in June a scheduled visit by Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) for high level meetings was canceled by the US after China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平) asked Trump to curb US engagement with Taiwan during a June phone call. The cancellation of Lai’s transit was a gaudy

The centuries-old fiery Chinese spirit baijiu (白酒), long associated with business dinners, is being reshaped to appeal to younger generations as its makers adapt to changing times. Mostly distilled from sorghum, the clear but pungent liquor contains as much as 60 percent alcohol. It’s the usual choice for toasts of gan bei (乾杯), the Chinese expression for bottoms up, and raucous drinking games. “If you like to drink spirits and you’ve never had baijiu, it’s kind of like eating noodles but you’ve never had spaghetti,” said Jim Boyce, a Canadian writer and wine expert who founded World Baijiu Day a decade