The biblical story of Babel takes up a handful of verses in the 11th chapter of Genesis, and it illustrates, among other things, the terrible consequences of unchecked ambition. As punishment for trying to build a tower that would reach the heavens, the human race was scattered over the face of the earth in a state of confusion — divided, dislocated and unable to communicate. More or less as we find ourselves today.

To make sense of this condition requires an ambition nearly as great as the one that got those ancient architects into trouble in the first place. Any discussion of Babel, therefore — whether grounded in skepticism or lost in admiration — has to begin by acknowledging just how much the film, the third collaboration between the director Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu and the screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga, sets out to do.

It tells four distinct stories, disclosing bit by bit the chronology and causality that link them and making much of the linguistic, cultural and geographical distances among the characters. The movie travels — often by means of jarringly abrupt cuts and shifts of tone — from the barren mountains of Morocco, where the dominant sound is howling wind, to fluorescent Tokyo, where the natural world has been almost entirely supplanted by a technological environment, to the anxious border between the US and Mexico. Each place has its own aural and visual palette. The languages used by the astonishingly diverse cast include Spanish, Berber, Japanese, sign language and English. The misunderstandings multiply accordingly, though they tend to be most acute between husbands and wives or parents and children, rather than between strangers.

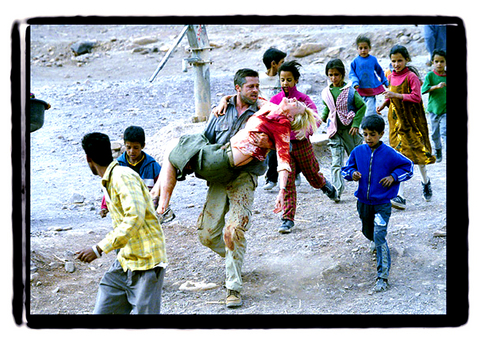

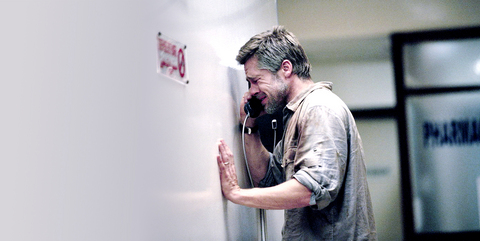

PHOTOS COURTESY OF FOX

Surely, something must hold this world — or, at any rate, this film's vision of the world — together. Whether anything does is the question most likely to fuel the cafe-table arguments Babel will surely provoke. The individual scenes are sometimes so powerful, and put together with such care and conviction, that you might leave the theater feeling dazed, even traumatized. Babel is certainly an experience. But is it a meaningful experience? That the film possesses unusual aesthetic force strikes me as undeniable, but its power does not seem to be tethered to any coherent idea or narrative logic. You can feel it without ever quite believing it.

But let's give feeling its due. The sheer reckless ardor of Gonzalez Inarritu's filmmaking — the voracious close-ups, the sweeping landscape shots, the swiveling, hurtling camera movements — suggests a virtually limitless confidence in the power of the medium to make connections out of apparent discontinuities. His faith in cinema as a universal language could hardly be more evident.

Some of the pieces of Babel are attached to one another by the banal lingua franca of television images, as events in North Africa, for instance, make the evening news in Tokyo. But Gonzalez Inarritu's own visual grammar tries to go deeper, to suggest a common idiom of emotion present in certain immediately recognizable gestures and expressions. We may not be able to read minds or decipher words, he suggests, but we can surely decode faces, especially when we see them at close range and in distress. Loss, fear, pain, anguish — none of these emotions, it seems, are likely to be lost in translation.

It gives nothing away to note that every story in Babel ends in tears. The raw, naturalistic intimacy of Rodrigo Prieto's cinematography disguises some flagrant melodrama, as does the dedication of the actors, some of whom have never appeared on film before.

The most glamorous cast members are Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett, who play an American couple on a desultory vacation in Morocco, trying to repair the damage done to their marriage by the death of their infant son. Their movie-star charisma is turned down to a low, flickering flame, and the easy sense of entitlement they sometimes betray belongs naturally to their characters, Susan and Richard, who nonetheless receive a brutal reminder that even the privileged are vulnerable to accident.

Susan — the kind of tourist who worries that the local ice cubes carry disease — is badly wounded when a bullet is fired through a bus window, hitting her in the neck. The bullet comes from a gun belonging to Abdullah (Mustapha Rachidi), a goatherd, and used by his two sons, Ahmed (Said Tarchani) and Yussef (Boubker Ait El Caid), to keep jackals away from the herd.

The gunmen and their victim are never in the frame together, and the consequences of the incident unfold in parallel crises. Susan and Richard wind up in a small town, waiting for an ambulance, facing the panic and impatience of their fellow holidaymakers and relying on the kindness of strangers. Abdullah and his sons and neighbors, for their part, must deal with the harsh attentions of the Moroccan police, who are trying to defuse what threatens to become an international incident.

Meanwhile, Richard and Susan's surviving children (Elle Fanning and Nathan Gamble) travel to Mexico with the family's housekeeper, Amelia (Adriana Barraza), whose son is getting married near Tijuana. They are accompanied by Amelia's roughneck nephew Santiago (Gael Garcia Bernal, who clearly relishes playing the heavy for once).

And in Tokyo, a deaf teenage girl named Chieko (Rinko Kikuchi) spins through the emotional upheavals of adolescence, which are intensified both by her disability — or, more precisely, the obtuse way other people respond to it — and by the aftershocks of her mother's death.

Chieko's brazen attempts to solicit attention result, again and again, in humiliation, and Kikuchi's performance is an unnerving blend of sexual provocation, timidity and sheer rage. Of all the characters in Babel, she seems most surprising and least tethered to cultural stereotype (in spite of the short-skirted schoolgirl uniform she wears). And her story, unfolding without evident connection to the other three, does not seem quite as bound by the fatalism that is Arriaga's hallmark — as well as his limitation — as a storyteller.

The splintered, jigsaw-puzzle structure of Babel will be familiar to viewers who have seen Amores Perros or 21 Grams, the other two features Arriaga and Gonzalez Inarritu have made together. Indeed, this movie belongs to an increasingly common, as yet unnamed genre — Crash is perhaps the most prominent recent example — in which drama is created by the juxtaposition of distinct stories, rather than by the progress of a single narrative arc.

Perhaps the most common feature of movies of this kind is that they are more interested in fate than in psychology. The people in Babel behave irrationally — if often quite predictably — but any control they appear to have over their own lives is illusory. They suffer unequally and unfairly, paying disproportionately for their own mistakes and for the whims of chance and the laws of global capitalism.

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by