Through the centuries many people have been haunted by the work of Raphael, but probably few have been haunted in quite the same way as Bernard Taper.

Even now, at 88, he says he finds a certain painting continuing to surface in his memory. It is an elegant portrait of a young man that Taper knew in 1947 only from a black-and-white photograph he had been given, much in the way a detective is handed a snapshot of a missing person.

At that time, in the ruinous aftermath of World War II in Europe, the Raphael portrait was one of the most prominent masterpieces to have disappeared, but it had considerable company. Thousands of paintings, sculptures and artifacts that had been looted by the Nazis — many of them bound for Hitler's long-envisioned Fuehrer Museum in Linz, Austria, his boyhood home, or confiscated for the collection of Hermann Goering, Hitler's chief art-looting rival — remained missing at war's end.

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Taper, then an Army lieutenant charged with tracking down the Raphael, spent months interrogating jailed Nazis and trying to connect the dots, but he never found the painting, which had been taken from a family museum in Krakow, Poland.

"I still dream about it sometimes," he said in a recent interview. "I wonder if it's out there."

The story might sound like grist for a Dan Brown novel or a Steven Spielberg treatment. But the efforts of Allied officers and soldiers like Taper to save and repatriate stolen treasures during and after the war is a chapter of World War II history still not particularly well known. Even during the war their work — when compared with saving lives and preserving ways of life — was sometimes discounted. Some members of the military referred to these soldiers as "Venus fixers," a term with more than a hint of the effete.

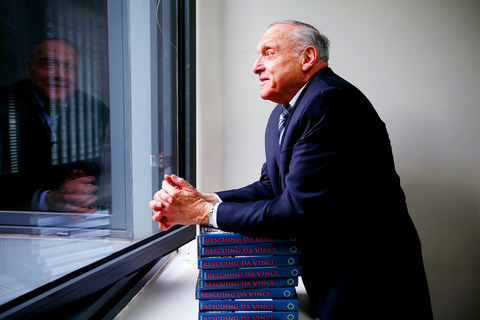

But the accomplishments of these soldiers, better known as the Monuments Men, are finally starting to come into sharper focus. Rescuing Da Vinci, a lavishly illustrated book devoted to them, with dozens of pictures newly unearthed from archives, has just been published by Robert M. Edsel, a retired Texas oilman. Edsel, 49, became obsessed with the story several years ago and even established a research office in Dallas, his hometown, with the goal of telling it better.

This month, in large part because of his work, the US Congress passed a resolution honoring the Monuments Men (whose number also included some women and civilians), saying that the value of their work "cannot be overstated and set a moral precedent" for the preservation of culture.

Edsel, who came late to an appreciation of art history, said in a recent interview that he became aware of the vast art-rescue story when he was living in Florence in the late 1990s and read The Rape of Europa, an award-winning book by Lynn H. Nicholas that chronicles the Third Reich's pillaging of museums, churches and private collections.

The book goes into considerable detail about the formation and work of what became the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives section of the US military, some of whose members had art backgrounds and would go on to become civilian art-world luminaries, like James J. Rorimer, a future director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Lincoln Kirstein, then a lowly private but later a founder of the New York City Ballet. Most of the recovery effort was American, but soldiers from more than a dozen countries also participated.

Edsel quickly became frustrated, he said, as he combed through other World War II history books and found surprisingly little about what he thought was a gripping story of high-culture derring-do. "To me," he said, "it was like, wow, you wrote a western and left out John Wayne. I couldn't believe it."

Armed with the kind of bluster and directness that made him wealthy in the oil business, Edsel sought out Nicholas "pretty much cold," he recalls. He asked for her guidance in putting together a book devoted exclusively to the Monuments Men, a book he eventually published himself, he said, because he got "absolutely no interest" from commercial publishers.

He paid researchers who set to work in Washington, Moscow, Munich and other cities. Even as this work was under way, he said, he knew that professionals in the art world like Nancy Yeide, curator of records at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, whom he approached about finding pictures, wondered whether he was just a well-meaning dilettante.

"I could tell that she didn't know whether to trust me, whether to think I was a kook, whether it was like some vanity project," he said.

But Edsel kept at it, putting US$2.5 million of his own money toward the project. Over time he also became a co-producer of a documentary based on Nicholas' book, which is now making the rounds of film festivals. He is planning exhibitions of the photographs and archival material featured in the book and is now crisscrossing the country trying to find and interviewing the few living members of the Monuments Men squad, like Taper.

"The problem is, we're in a race with time now," Edsel said in a recent interview conducted in New York.

The urgency of that race was underlined last month by the death of S. Lane Faison Jr., 98, an art-rescue officer who worked for the Office of Strategic Services, which helped the Monuments Men. Faison later became a renowned art professor at Williams College whose students went on to become directors and curators at many prominent American museums.

Edsel interviewed Faison before his death and tracked down several other former officers who helped recover thousands of paintings and artifacts. One, Harry Ettlinger, now 80, joined the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives in 1945 and was assigned to sort out the contents of a vast makeshift storehouse in Heilbronn, Germany. It was a salt mine where the Nazis had hidden thousands of crates of loot, including all the stained glass removed from the Strasbourg Cathedral in France, which Ettlinger helped return.

In Edsel's book Ettlinger can be seen in a crisp black-and-white photograph that could serve as the inspiration for a climactic movie scene: He and an officer are standing deep in the mine, staring in awe at a Rembrandt self-portrait that has just been raised from its crate.

But in a telephone interview Ettlinger said that much of the work done by the Monuments Men was not particularly cinematic. It was the tedious but immense job of archiving, translating documents, collating records and extracting needles from thousands of haystacks to ensure that works returned to their rightful homes. And it was frustrating: For every paper trail that led to a restitution, there were many more that led nowhere, and priceless works that were never found.

Of course, in the midst of the paperwork, there was a little wartime drama every so often down in the mine shafts, Ettlinger recalled.

"I remember once in a hallway I saw a doorway that was bricked in and no one knew what was behind it," he said. He ordered someone to find out. "And lo and behold it was nitroglycerin, which was about to come along and blow us all to kingdom come, never mind the art."

Edsel said the more he delved into the stories of the men, the more amazed he became at how little Americans seem to know about it, especially in an era with a newfound devotion to the Greatest Generation.

So, he was asked, is a feature film somewhere down the road?

He smiled and, in his best Texas dare-me voice, said not to rule it out.

"This has got heroes," he said. "It's got buried treasure. It's got untold stories. It's got everything. You want excitement? We've got it in spades right here."

Wooden houses wedged between concrete, crumbling brick facades with roofs gaping to the sky, and tiled art deco buildings down narrow alleyways: Taichung Central District’s (中區) aging architecture reveals both the allure and reality of the old downtown. From Indigenous settlement to capital under Qing Dynasty rule through to Japanese colonization, Taichung’s Central District holds a long and layered history. The bygone beauty of its streets once earned it the nickname “Little Kyoto.” Since the late eighties, however, the shifting of economic and government centers westward signaled a gradual decline in the area’s evolving fortunes. With the regeneration of the once

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

In February of this year the Taipei Times reported on the visit of Lienchiang County Commissioner Wang Chung-ming (王忠銘) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a delegation to a lantern festival in Fuzhou’s Mawei District in Fujian Province. “Today, Mawei and Matsu jointly marked the lantern festival,” Wang was quoted as saying, adding that both sides “being of one people,” is a cause for joy. Wang was passing around a common claim of officials of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the PRC’s allies and supporters in Taiwan — KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party — and elsewhere: Taiwan and

Perched on Thailand’s border with Myanmar, Arunothai is a dusty crossroads town, a nowheresville that could be the setting of some Southeast Asian spaghetti Western. Its main street is the final, dead-end section of the two-lane highway from Chiang Mai, Thailand’s second largest city 120kms south, and the heart of the kingdom’s mountainous north. At the town boundary, a Chinese-style arch capped with dragons also bears Thai script declaring fealty to Bangkok’s royal family: “Long live the King!” Further on, Chinese lanterns line the main street, and on the hillsides, courtyard homes sit among warrens of narrow, winding alleyways and