Outside this improbable spa in a remote part of the former Soviet Union, oil rigs bob on a hardscrabble plain of rocks, shrubs and rusting industrial equipment that could easily pass for a stretch of West Texas.

Inside, Ramil Mutukhov, a lanky 25-year-old, prepares to be pampered and preened, scrubbed and peeled — in a bath of pure crude oil.

He undresses, hangs his trousers and sweatshirt on a peg, pulls off socks and underwear and folds a wad of brown paper towels. He will need them later. Then he steps into a mess of what looks, smells and flows like used engine oil. "It's wonderful," he says, up to his neck in oil in a sort of human lube job.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

The petroleum spas of Naftalan in central Azerbaijan, one of the little-known but once popular vacation spots of the Soviet Union, are making an unlikely return in a country so awash in oil these days that people are swimming in it.

Here in Naftalan, visitors can bathe once a day in the local crude. They and doctors here say it relieves joint pain, cures psoriasis, calms nerves and beautifies skin — never mind that Western experts say it may cause cancer.

Hoping to tap into the worldwide spa boom, Health Center, where Mutukhov took a dip in crude recently, opened a year ago. Another spa is under construction and two more are planned. "Two years ago, all this was ruins," Ilgar Guseynov, the owner and director of Health Center, said in an interview. "Every day, every month, Azerbaijan is growing richer."

At their peak in the 1980s, Naftalan spas had 75,000 visitors a year. That flow became a trickle after war broke out between Azerbaijan and ethnic Armenians in nearby Nagorno-Karabakh in 1988 — and after the Soviet Union stopped offering free trips. In this depressed atmosphere, five of the six Soviet-era resorts were converted into glum housing for refugees. But this summer, about 350 people visited the Health Center, Guseynov said, up from 250 last summer. A 15-day course costs US$450, including meals.

"Azerbaijan is standing on its own feet now," Amir Aslan, the deputy mayor of Naftalan, said. The town is banking on growth tied to the oil spa, which he said would pull this dusty place out of poverty. Aslan has his own plans for a US$3 million, 20-bath spread.

In her office overlooking the oil field that supplies Health Center, Gyultikin Suleymanova, the lead doctor, said that the local crude was unusual because it contained little natural gasoline or other lighter fractions of petroleum, and as a result was safe.

Naftalan crude contains about 50 percent naphthalene, a hydrocarbon best known as the stuff of moth balls. It is also an active ingredient in coal tar soaps, which are used by dermatologists to treat psoriasis, though in lower concentrations.

The National Agency for Research on Cancer, an American government agency, classifies naphthalene as a possible carcinogen, though Suleymanova said that is not the case when people bathe in it. Baths are lukewarm and last 10 minutes.

The therapeutic benefits are a product of natural antibiotic and anti-inflammatory agents that seep into the skin though osmosis, Suleymanova said.

Arzu Mirzeyev is the bath master. With a green frock, jeans stained with oil spots and a mustache, he looks for all the world like a gas station attendant and has a job to match. He changes the oil.

Each bath uses about a barrel of crude, which is recycled into a communal tank for future bathers, given the cost of oil these days. Mirzeyev also uses paper towels to wipe bathers clean, a long, hard process that involves several showers.

He says he likes his job. Until Azerbaijan's economy ticked up over the last two years, Mirzeyev, 40 and a father of three, was a seasonal laborer in Ukraine, where wages were higher.

"If we have visitors, then we have work," Aslan said.

Unlike the oil from Azerbaijan's offshore deposits, sold internationally under the brand Azeri Light crude, Naftalan's oil is too heavy to have much commercial value. Luckily, because most of the bath attendants and patients seemed to smoke, it is not particularly flammable, either.

The resort has 80 rooms and 10 tubs, five for women, five for men. The tubs are not scoured between baths, and as might be expected, have perhaps the world's worst bathtub rings — greasy and greenish brown.

Oil has been Azerbaijan's ticket for a long time.

Oil seepages have been noted in Naftalan since at least the 13th century, when Marco Polo passed through and, even today, a reedy marsh, about the size of a football field, has a black patina of oil on the water. The site was a stopping place on the Silk Road to China.

Later, Azerbaijan's larger oil reserves on the Caspian coast were developed by the Swedish Nobel brothers, the rivals of the American oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller.

In a sign of the more recent past in Naftalan, a museum keeps a collection of wooden crutches left by Soviet-era visitors "cured" by oil at the peak of the Soviet oil spa boom in the 1970s and 1980s.

The museum also has a photograph of a sign that hung at the city limits back then, "He Who Has Naftalan Has Everything."

From the last quarter of 2001, research shows that real housing prices nearly tripled (before a 2012 law to enforce housing price registration, researchers tracked a few large real estate firms to estimate housing price behavior). Incomes have not kept pace, though this has not yet led to defaults. Instead, an increasing chunk of household income goes to mortgage payments. This suggests that even if incomes grow, the mortgage squeeze will still make voters feel like their paychecks won’t stretch to cover expenses. The housing price rises in the last two decades are now driving higher rents. The rental market

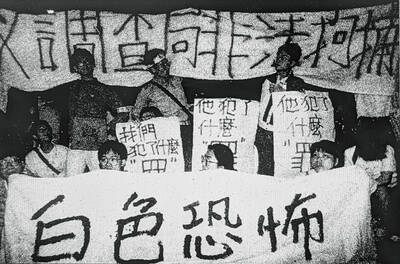

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

Hualien lawmaker Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) is the prime target of the recall campaigns. They want to bring him and everything he represents crashing down. This is an existential test for Fu and a critical symbolic test for the campaigners. It is also a crucial test for both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a personal one for party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫). Why is Fu such a lightning rod? LOCAL LORD At the dawn of the 2020s, Fu, running as an independent candidate, beat incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmaker Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and a KMT candidate to return to the legislature representing

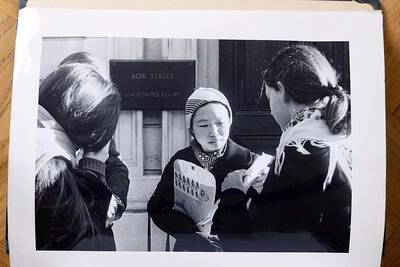

Fifty-five years ago, a .25-caliber Beretta fired in the revolving door of New York’s Plaza Hotel set Taiwan on an unexpected path to democracy. As Chinese military incursions intensify today, a new documentary, When the Spring Rain Falls (春雨424), revisits that 1970 assassination attempt on then-vice premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國). Director Sylvia Feng (馮賢賢) raises the question Taiwan faces under existential threat: “How do we safeguard our fragile democracy and precious freedom?” ASSASSINATION After its retreat to Taiwan in 1949, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regime under Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) imposed a ruthless military rule, crushing democratic aspirations and kidnapping dissidents from