Following a highly successful 2004 in which he won best director awards at the Berlin and Venice International Film Festivals for Samaritan Girl and 3 Iron respectively, South Korean film master Kim Ki-duk returns to his disturbing take on life, human nature, love and suffering in his latest work Hwal (The Bow), which is slated for release this weekend in Taipei.

Famed for poignantly exploring twisted human minds with an abundance of explicit sex, violence and cruelty, Kim's Hwal is yet another film that deals with distorted human relations, but his latest work is handled with subtlety and restraint, illustrating the South Korean director's growth as a filmmaker.

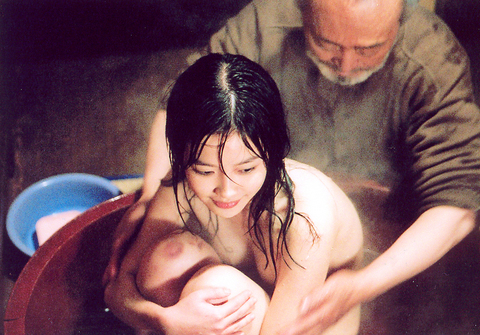

Hwal is Kim's twelfth film since his directorial debut Crocodiles in 1996. Shot in less than three weeks with a limited budget on a remote island off the city of Incheon, South Korea, the action takes place on a fishing boat at sea. On the boat live a 16-year-old girl (played by Han Yeo-reum from Samaritan Girl) and an old man of 60 (played by Jeon Sung-hwan) who is madly in love with the girl and plans on marrying her when she turns 17. As the film progresses, we quickly learn that the old man found the girl 10 years ago and has been raising her ever since. But how exactly she was found and brought to the boat is never made clear.

Together the pair make a living providing fishermen with a place to enjoy a few beers. The two main characters never utter a single line of dialogue. Everything we learn about the two is mediated through the conversations of the guests on the boat, the body language between them and the symbolic meaning of each object shown in the film. The old man's longbow plays an important role in the film. It is the weapon that he brandishes feverishly to protect the girl from the covetous eyes of other men.

One day a handsome young man arrives on the boat. The two youngsters instantly fall for each other. The bow that signifies the old man's sexuality and power fails, and he knows that he will soon lose the object of his affections and that the loss will be too much for him to bear.

According to director Kim, the bow takes on multiple meanings in his film. As a weapon to protect and also imprison the girl, the bow can be seen as a powerful, destructive tool used to protect one's world from the threat of outside influences. But when it is used as a musical instrument, the bow can play ritual music and becomes a communication medium with the outside world.

PHOTO COURTESY OF HUA ZHAN FILM

Kim delivers the film's motif in a line at the end of the film: "Power and a beautiful voice are like a taut bow? I want to live like this until I draw my last breath."

The director wants to manifest the beauty of human nature through the selfish and fiery passion of the old man towards the girl. The old man realizes the precious value of human life at the moment of his death -- the beauty of an eternal longing for other human beings.

Hwal is a work of simple yet eloquent poetry. The isolated location and lack of dialogue serve not to distract but to enhance the intense and complex emotions of the characters. This method of storytelling creates a genuine and honest drama. As director Kim once explained, spoken words always deceive, but the body's movements never lie.

Without formal training in filmmaking, the Korean director veers away from fancy camera movements or sumptuous scenes and lighting to create an honest visual work of lyrical simplicity that isolates something essential about human nature and experience.

Aug. 4 to Aug. 10 When Coca-Cola finally pushed its way into Taiwan’s market in 1968, it allegedly vowed to wipe out its major domestic rival Hey Song within five years. But Hey Song, which began as a manual operation in a family cow shed in 1925, had proven its resilience, surviving numerous setbacks — including the loss of autonomy and nearly all its assets due to the Japanese colonial government’s wartime economic policy. By the 1960s, Hey Song had risen to the top of Taiwan’s beverage industry. This success was driven not only by president Chang Wen-chi’s

Last week, on the heels of the recall election that turned out so badly for Taiwan, came the news that US President Donald Trump had blocked the transit of President William Lai (賴清德) through the US on his way to Latin America. A few days later the international media reported that in June a scheduled visit by Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) for high level meetings was canceled by the US after China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平) asked Trump to curb US engagement with Taiwan during a June phone call. The cancellation of Lai’s transit was a gaudy

From Godzilla’s fiery atomic breath to post-apocalyptic anime and harrowing depictions of radiation sickness, the influence of the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki runs deep in Japanese popular culture. In the 80 years since the World War II attacks, stories of destruction and mutation have been fused with fears around natural disasters and, more recently, the Fukushima crisis. Classic manga and anime series Astro Boy is called “Mighty Atom” in Japanese, while city-leveling explosions loom large in other titles such as Akira, Neon Genesis Evangelion and Attack on Titan. “Living through tremendous pain” and overcoming trauma is a recurrent theme in Japan’s

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in