Previously unpublished letters by Albert Einstein to a Japanese pen pal show the physicist to be defensive over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki which became possible partly through his genius.

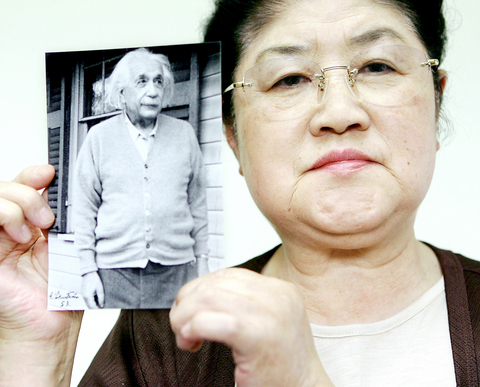

The widow of Seiei Shinohara, a philosopher and German-Japanese translator who corresponded with Einstein in the last years of the scientist's life, has chosen to go public with the letters on the 60th anniversary of the world's only nuclear attacks.

Einstein's opposition to nuclear warfare has already been documented, but his letters to Shinohara also show him defending himself on a personal level and trying to reconcile his pacifism.

PHOTO: AFP

The correspondence began in 1953 when Shinohara sent a letter to Einstein criticizing the physicist over his role in developing nuclear weapons.

Einstein responded by hand on the back of the typed letter, beginning his rebuttal without bothering to offer greetings.

"I have always condemned the use of the atomic bomb against Japan but I could not do anything at all to prevent that fateful decision," Einstein wrote in German to Shinohara in a letter dated June 23, 1953.

This year marks the centennial of Einstein's theory of relativity. He argued that distance and time are not absolute, leading to his most famous formula, E=mc2, which was essential for the development of the atomic bombs dropped on Japan by the US.

The Hiroshima bombing killed around 140,000 people -- almost half the city population of the time -- immediately or in the months afterward from radiation injuries or horrific burns.

More than 70,000 more people died three days later in the bombing of Nagasaki. After six days Emperor Hirohito went on the radio for the first time to announce the surrender of Japan, which since the war has campaigned to abolish nuclear weapons.

"The only consolation, it seems to me, in the development of nuclear bombs is that this time the deterrent effect will prevail and the development of international security will accelerate," Einstein wrote in another letter.

`Convinced pacifist'

But Einstein, whose Jewish origins led him to flee Germany in 1933 for the US after Adolf Hitler came to power, also said that war was sometimes acceptable.

"I didn't write that I was an absolute pacifist but that I have always been a convinced pacifist. That means there are circumstances in which in my opinion it is necessary to use force," he wrote.

"Such a case would be when I face an opponent whose unconditional aim is to destroy me and my people," he said. "Therefore the use of force against Nazi Germany was in my opinion justified and necessary."

Shinohara, who studied philosophy in Germany before returning to Tokyo in 1947, died of a stroke in 2001 at age 89. His letters have since been kept in private by his widow, Nobuko Shinohara.

The correspondence ended in July 1954, a year before Einstein died, dashing Shinohara's dream to meet the physicist face to face.

"My husband first sent the letter with anger and I guess Dr Einstein replied with annoyance," said Shinohara, 80.

"But later Dr Einstein and my husband formed a friendship through exchanging letters," she said.

She noted that this year was designated as "Einstein Year" to mark the 100th anniversary of three of the physicist's four papers that changed the way we view the universe.

"I decided to look for a suitable museum to display the letters in public because I reached a conclusion that it's good for a lot of people to have a chance of seeing them directly," Shinohara said.

"I hope to donate the letters soon because this year is a remarkable year -- the 60th anniversary of the atomic bombs and the end of World War II," she said.

"I think his letters are a great message from Dr Einstein to everybody in modern times as we are still struggling to reduce nuclear weapons."

The couple sent a Japanese doll and traditional pictures to Einstein while receiving in return his black-and-white photograph with his autograph.

"My husband repeatedly told me he really missed Dr Einstein after his death," Shinohara said. "He told me there were a lot of other things to discuss with Dr Einstein."

Several museums have already made requests seeking the letters for their collections, according to Yutaka Sakuma, a lawyer handling the papers.

Under pressure, President William Lai (賴清德) has enacted his first cabinet reshuffle. Whether it will be enough to staunch the bleeding remains to be seen. Cabinet members in the Executive Yuan almost always end up as sacrificial lambs, especially those appointed early in a president’s term. When presidents are under pressure, the cabinet is reshuffled. This is not unique to any party or president; this is the custom. This is the case in many democracies, especially parliamentary ones. In Taiwan, constitutionally the president presides over the heads of the five branches of government, each of which is confusingly translated as “president”

Sept. 1 to Sept. 7 In 1899, Kozaburo Hirai became the first documented Japanese to wed a Taiwanese under colonial rule. The soldier was partly motivated by the government’s policy of assimilating the Taiwanese population through intermarriage. While his friends and family disapproved and even mocked him, the marriage endured. By 1930, when his story appeared in Tales of Virtuous Deeds in Taiwan, Hirai had settled in his wife’s rural Changhua hometown, farming the land and integrating into local society. Similarly, Aiko Fujii, who married into the prominent Wufeng Lin Family (霧峰林家) in 1927, quickly learned Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) and

The low voter turnout for the referendum on Aug. 23 shows that many Taiwanese are apathetic about nuclear energy, but there are long-term energy stakes involved that the public needs to grasp Taiwan faces an energy trilemma: soaring AI-driven demand, pressure to cut carbon and reliance on fragile fuel imports. But the nuclear referendum on Aug. 23 showed how little this registered with voters, many of whom neither see the long game nor grasp the stakes. Volunteer referendum worker Vivian Chen (陳薇安) put it bluntly: “I’ve seen many people asking what they’re voting for when they arrive to vote. They cast their vote without even doing any research.” Imagine Taiwanese voters invited to a poker table. The bet looked simple — yes or no — yet most never showed. More than two-thirds of those

In the run-up to the referendum on re-opening Pingtung County’s Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant last month, the media inundated us with explainers. A favorite factoid of the international media, endlessly recycled, was that Taiwan has no energy reserves for a blockade, thus necessitating re-opening the nuclear plants. As presented by the Chinese-language CommonWealth Magazine, it runs: “According to the US Department of Commerce International Trade Administration, 97.73 percent of Taiwan’s energy is imported, and estimates are that Taiwan has only 11 days of reserves available in the event of a blockade.” This factoid is not an outright lie — that