The Manchurian Candidate is Jonathan Demme's second attempt to update a classic Cold-War thriller. Two years ago, in The Truth About Charlie, he tried to drag Charade, Stanley Donen's suave Hitchcockian romance, into the messy, multicultural modern world, an admirable effort that unfortunately did not yield a very enjoyable movie, in spite of the charms of Thandie Newton.

This time, using John Frankenheimer's original adaptation of Richard Condon's novel as a touchstone rather than a template, Demme has been more successful. Not only has he made a political thriller that manages to be at once silly and clever, buoyantly satirical and sneakily disturbing, but he has recovered some of the lightness and sureness of touch that had faded from his movies after The Silence of the Lambs.

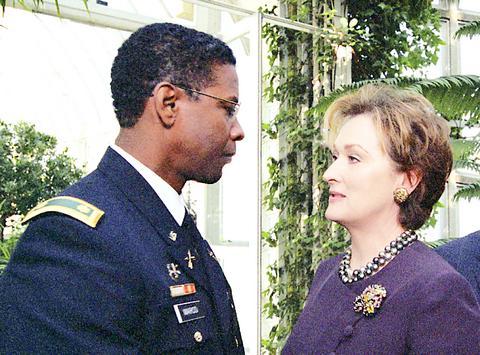

PHOTO COURTESY OF UNIVERSAL PICTURES

Some of the fun of his retrofitted Candidate, which opens with Wyclef Jean's bracing version of John Fogerty's Fortunate Son, comes from its playful acknowledgment of -- and frequent departure from -- the first version, which was released in 1962, just in time for the Cuban missile crisis. The very first scenes peek in on a long, raucous game of poker, and fans of Frankenheimer's movie may anticipate the fateful appearance of the queen of diamonds. But this, like other winking evocations of the old Candidate, is a tease.

The game Demme and the screenwriters, Daniel Pyne and Dean Georgaris, are playing involves a different set of strategies and symbols, as well as altered stakes.

The first Manchurian Candidate was an exemplary piece of liberal paranoia, imagining the nefarious collusion between foreign, Communist totalitarians and their most ferocious domestic enemies, a conspiracy of the political extremes against the middle. That film, which climaxed at the 1956 Republican convention in New York, looked back from Camelot at an almost-plausible alternative history with a mixture of alarm and relief. The center, in the solid person of John F. Kennedy's pal Frank Sinatra, had held.

The new version, after a prologue in the first Persian Gulf war, unfolds at a time succinctly and scarily identified as "today," and proceeds from the nominating convention of a major political party toward a frenzied Election Night finale, feeding on an anxiety about the future that is neither exaggerated nor easily assuaged. Frank Sinatra's character, Major Ben Marco, is played by Denzel Washington, and this time Marco is not the cool, rational unraveler of a vast conspiracy, but rather one of its victims.

The public may be more

interested in identifying the perpetrators. Though the party in question is not identified, it does not much resemble the real-world party currently in power. In the movie the US is subject to terrorist attacks, which have become so routine that they are mentioned only in passing, and is fighting wars in small countries around the world.

The chief danger to the republic, however, emanates not from the extremes -- a fanatical foreign enemy combined with a zealous administration -- but from the center, from the moderate wing of the opposition party and its corporate sponsors.

In a smokeless back room at the convention, a venerable, liberal senator, played by Jon Voight (who does this kind of thing so often you may think he's playing himself), is dumped from the ticket in favor of Raymond Shaw (Liev Schreiber), a young New York congressman whose mother, Senator Eleanor Shaw (Meryl Streep), is a formidable power broker and a tireless promoter of her son's career.

You may notice a slight resemblance to a certain real-life New York senator, but Streep's swaggering, ice-cube-chewing performance is too full of inspired, unpredictable mischief to be mere mimickry.

Poor Raymond, a queasy-looking fellow who won the Congressional Medal of Honor for heroism in the gulf war, turns out to be at the center of a diabolical conspiracy involving military adventurism, maternal monstrousness and big business string-pulling.

"Manchurian" no longer refers to a region in China, but rather to a multinational defense conglomerate whose mind-control techniques are much more high-tech then the Maoist-Freudian brainwashing methods that were popular back in 1962.

Wooden houses wedged between concrete, crumbling brick facades with roofs gaping to the sky, and tiled art deco buildings down narrow alleyways: Taichung Central District’s (中區) aging architecture reveals both the allure and reality of the old downtown. From Indigenous settlement to capital under Qing Dynasty rule through to Japanese colonization, Taichung’s Central District holds a long and layered history. The bygone beauty of its streets once earned it the nickname “Little Kyoto.” Since the late eighties, however, the shifting of economic and government centers westward signaled a gradual decline in the area’s evolving fortunes. With the regeneration of the once

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

In February of this year the Taipei Times reported on the visit of Lienchiang County Commissioner Wang Chung-ming (王忠銘) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a delegation to a lantern festival in Fuzhou’s Mawei District in Fujian Province. “Today, Mawei and Matsu jointly marked the lantern festival,” Wang was quoted as saying, adding that both sides “being of one people,” is a cause for joy. Wang was passing around a common claim of officials of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the PRC’s allies and supporters in Taiwan — KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party — and elsewhere: Taiwan and

Perched on Thailand’s border with Myanmar, Arunothai is a dusty crossroads town, a nowheresville that could be the setting of some Southeast Asian spaghetti Western. Its main street is the final, dead-end section of the two-lane highway from Chiang Mai, Thailand’s second largest city 120kms south, and the heart of the kingdom’s mountainous north. At the town boundary, a Chinese-style arch capped with dragons also bears Thai script declaring fealty to Bangkok’s royal family: “Long live the King!” Further on, Chinese lanterns line the main street, and on the hillsides, courtyard homes sit among warrens of narrow, winding alleyways and