To found a city is to establish a civilization. When a city falls, civilization ends. These are our most ancient stories, perpetually retold by tragedy and epic. Aeneas escapes from ruined Troy and in compensation builds a new city in Rome; as the cycle repeats itself, Rome is vengefully besieged by Hannibal. Contemporary history brings the cycle up to date. The Greeks burned what Marlowe called the "topless towers" of Troy, just as al-Qaeda targeted the haughty mercantile skyscrapers of Manhattan. This week New York will be destroyed once more in Roland Emmerich's The Day After Tomorrow.

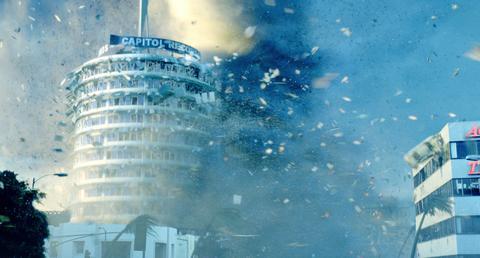

This time the avenging armies have been replaced by nature's fury. As the polar ice melts, an omnivorous ocean rolls in to swamp the city, and a frigid storm kills 7 million people. It is all due to happen, as the film's title predicts, at any moment. Suddenly the future has caught up with us: we are staring at the end of time. No terrorists are necessary since Emmerich's digital wizardry capsizes the world's cities for our delectation. A hailstorm of cold, jagged meteorites batters Tokyo, tornadoes playfully tear Los Angeles apart, and then that hungry wave engulfs Manhattan. The enemy in this case is our imaginations, avid for the spectacle of catastrophe.

PHOTO COURTESY OF TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX

Ever since New York became a global capital we have been dreaming up disasters with which to assail it. Oswald Spengler, the historical prophet consulted by the Nazis, concluded that "the rise of New York" was "the most pregnant event of the 19th century," the 20th century, therefore, laid plans for the city's fall. Spengler envisaged Manhattan as "the stone colossus that stands at the end of the life-course of every great culture," an image of spirit materialized in concrete and steel. The arrogant colossus begs to be knocked off its pedestal. Hence, in New York's imaginary necrology, the upsets suffered by the Statue of Liberty. In Planet of the Apes the allegorical matron lies humbled in a sand dune, and in The Day After Tomorrow she raises an ineffectual arm above the snow drifts, still gripping a torch that has been quenched by ice.

PHOTO COURTESY OF TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX

Sometimes the apocalypse arrives in the form of a dismissive breeze that blows away the monuments to our presumption. Bertolt Brecht in a poem written during the 1920s surveyed the "tall boxes on the island of Manhattan" and predicted that "of such cities will remain what passes through them, the wind!"

Wells recognized the inevitability of what he so far-seeingly imagined: New York had to be wrecked, "because she was too strong to be occupied, and too proud to surrender." By 1908, when he wrote this, such previews of apocalypse were already commonplace, and it was the Americans, not their enemies, who self-destructively dreamed them up. In 1889, J.A. Mitchell's novel The Last American warned about "the sudden rise and swift extinction of a foolish people." Explorers in the year 2951 pick their way through the remnants of a civilization they call Mehrikan, which was laid low after a massacre of Protestants in 1927 incited decades of religious warfare.

It gradually becomes clear that the necropolis is New York, though a jungle has pushed its way through the pavements of Fifth Avenue and only the anchorage of the Brooklyn Bridge protrudes uselessly from the river. One remaining savage crawls from the undergrowth and is killed beneath "a large sitting image of George-wash-yn-tun," the defunct god of these exterminated people. The archeological narrator, who has traveled here to collect souvenirs, turns out to be Persian.

For Spengler, New York was the loftiest creation of the over-stretched Western world; after its fall, the rise of an Eastern empire begins.

Roland Emmerich blew up the White House and made skyscrapers buckle like molten wax in Independence Day. He might have been expected to do more of the same in The Day After Tomorrow, but his new film is surprisingly sober. These days pyrotechnics are best left to al-Qaeda, whose hijackers on Sept. 11 wrote, directed and acted in their own disaster movie. Emmerich, placating the foe, makes penitent amends by disarming belligerent America: a new president apologizes for the country's gas-guzzling (which prompts the climatic upheaval) and humbly thanks "what we used to call the Third World" for offering a haven to the refugee population of the US. And as the film ends, helicopters rescue survivors who have escaped drowning by clambering up to the tops of skyscrapers: high-rises, you see, are life-savers after all!

When the purging water pours into New York, Emmerich ventures to undo the moral and psychological damage inflicted by Sept. 11. The World Trade Center collapsed because all that aviation fuel

ignited inside it.

The teenage protagonists of The Day After Tomorrow visit the Natural History Museum in New York and admire a Siberian mammoth, still intact with a gullet full of food after it was overtaken by the onset of the first Ice Age. Of course it's dead, but it has left a good-looking corpse: surely that must be some consolation.

During the storm, we watch as the Empire State Building turns into an icy stalagmite, glittering and tinkling as the cold courses down from its needling spire; Spengler's stone colossus is now a glacial ornament. This is Emmerich's grandest image, and it acknowledges that cities are immortal artworks, indifferent to their human inhabitants. Imagining these disasters, we wish ourselves out of the way -- though we hope that we might return as ghosts, to look at the beautiful world we created and then destroyed.

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by