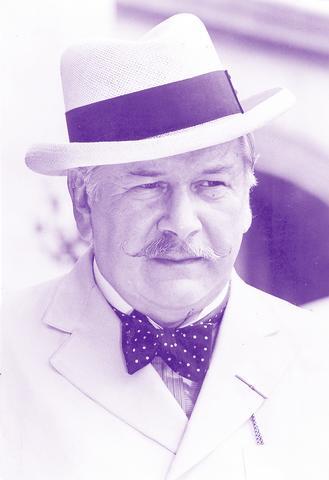

Peter Ustinov, the hair-trigger wit with the avuncular charm whose 60-year career amounted to a series of star turns as actor, playwright, novelist, director and raconteur, died Sunday at a clinic near his home in Bursins, Switzerland. He was 82.

Ustinov had suffered for years from the effects of diabetes and, more recently, a weakened heart. His death was announced by Leon Davico, a friend and former spokesman for UNICEF, for which Ustinov worked for many years.

Ustinov, a cosmopolitan, corpulent 6-footer whose ancestors were prominent in czarist Russia, was a prodigy who began mimicking his parents' guests at the age of two. He wrote his first play, House of Regrets, in his teens; it opened in London to glowing reviews when he was 21.

PHOTOS: NY TIMES

As an actor, Ustinov won international stardom as a languid, quirky Nero in the 1951 sword-and-sandal epic Quo Vadis? He gained increasing stature by playing sly rogues and became one of the few character actors to hold star status for decades, adjusting easily to movies, plays, broadcast roles and talk shows, which he enlivened with hilarious imitations and pungent one-liners.

He won two supporting-actor Academy Awards, one for his portrayal of a shrewd slave dealer in Spartacus in 1960, the other for his role as a clumsy jewel thief in Topkapi in 1964. He received three Emmys for television performances: in the title role of The Life of Samuel Johnson in 1958, as Socrates in Barefoot in Athens in 1966 and as a rural shopkeeper who gains compassion from a youngster in A Storm in Summer in 1970. He won a Grammy for narrating Prokofiev's Peter and the Wolf.

Reviewing A Storm in Summer, Jack Gould of The New York Times praised Ustinov for shaping "an exquisite portrait of the individual who had known more than his share of sorrow, yet in his disgruntled way clung to noble values." The critic lauded Ustinov's "incredible virtuosity" and hailed him as "one of the most gifted actors of our time."

Other reviewers occasionally accused Ustinov of approaching comedy more decoratively than genuinely, of overdoing mugging and mannerisms and of pretentiousness in playing historical figures.

In the last decade, Ustinov appeared in a half dozen films for television or general release. Among them was Luther, Eric Till's study of Martin Luther, in which Ustinov portrayed Freidrich the Wise. By late in the film, Ustinov said in an interview with The New York Times, he understood why, during the 16th century, everyone died at the age of 40 or earlier: "Because having to dress up in curtains, which press the human body in all sorts of places where it's not usually pressed, was real agony."

More recently Ustinov portrayed a doctor in the film Lorenzo's Oil (1992), and was the Walrus in the 1999 TV movie version of Alice in Wonderland.

His more than two dozen plays included two spoofs of the Cold War. One, The Love of Four Colonels, won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award as the best play of 1953, and the second, Romanoff and Juliet, received the British Critics' Best Play award for 1956.

His greatest film achievement was his co-adaptation, direction, production, and performance in the 1962 film Billy Budd, Herman Melville's nautical allegory on good and evil.

Among other honors, Ustinov was appointed a commander of the British Empire in 1975 and was elected to the Academie Francaise in 1988.

Ustinov visited the Soviet Union often and in 1988 he flew to Leningrad for the opening of an art museum dedicated to his mother's family and housed in a building erected by one of his great-great-grandfathers. That year he was also host of a miniseries based on his book My Russia, likening the changes in Soviet society under Mikhail Gorbachev to "an abscess bursting and health returning."

Ustinov's writing was usually praised for wit, literacy and insights, but the consensus was that his work, though clever and diverting, suggested more than it accomplished. Reviewers agreed that his early plays showed great promise, but over the years they increasingly criticized his writing as that of an undisciplined jack of all trades who frittered away his talents and was at times self-indulgent and verbose. Still, the critic John Lahr hailed the spirited autobiography Dear Me as "an unusually graceful memoir whose wit bears witness to Ustinov's generosity and

seriousness."

The entertainer maintained a frenetic professional pace. Asked to explain his abhorrence of retirement, he replied, "I've always considered life to be much more of a marathon than a sprint."

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Toward the outside edge of Taichung City, in Wufeng District (霧峰去), sits a sprawling collection of single-story buildings with tiled roofs belonging to the Wufeng Lin (霧峰林家) family, who rose to prominence through success in military, commercial, and artistic endeavors in the 19th century. Most of these buildings have brick walls and tiled roofs in the traditional reddish-brown color, but in the middle is one incongruous property with bright white walls and a black tiled roof: Yipu Garden (頤圃). Purists may scoff at the Japanese-style exterior and its radical departure from the Fujianese architectural style of the surrounding buildings. However, the property