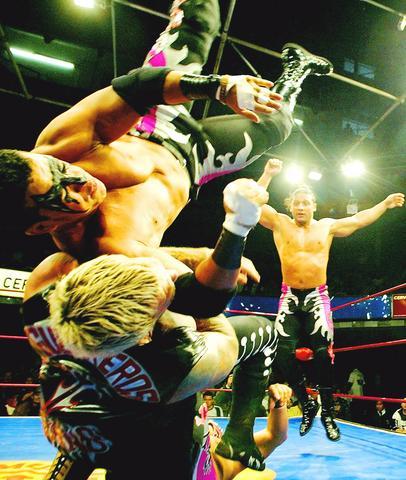

To the blaring sound of the Queen anthem We Will Rock You, wrestlers dressed in scary masks and long colorful capes take to the stage in front of thousands of screaming Mexican fans.

With names like Black Abyss, Starman and Great Warrior, the wrestlers are heirs of the decades-old wrestling tradition of Free Fight, a raucous mixture of sport, circus and pure show.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Free Fight, known in Spanish as Lucha Libre, is more acrobatic than its professional wrestling counterpart in the US and Europe and has taken off in Japan.

The rules are mostly the same as in US professional wrestling but Mexican fighters use less force than US wrestlers and specialize in spectacular leaps.

Fight fans are passionate.

Every Sunday, Dolores Garcia, a women in her 70s, sits at the front row of the Arena Coliseo auditorium in Mexico City, where 4,000 people attend Free Fights once a week.

"Kill him, kill him," she shouted at her favorite, a long-haired wrestler known as Canadian Vampire, who wears Lycra pants with fuchsia and silver stripes.

`Free fight'

Garcia regularly attends fights with her children and grandchildren. Tickets cost between US$5 and US$10.

"I have been coming since 1950 but not for the kids, for me. I want to get up there and hit the Rulebreakers but I can't," she said.

In Free Fight, wrestlers are traditionally either good guys, known as Craftsmen, or baddies, the Rulebreakers, who will pull any dirty trick to win.

Black Abyss, dressed in a red body suit and mask, is an unashamed Rulebreaker who will stoop to assaulting an opponent with an aerosol spray if need be.

"Black Abyss is not of this world. He comes from another galaxy and is an evil being who is exiled because of his badness," the wrestler said. "But a meteorite diverts him to Earth where he is mutated into a professional wrestler.

"But out of the ring we are normal human beings," he said. Free Fight wrestlers rarely reveal their real names so as not to spoil the mystery surrounding their character.

One wrestler who could not hide his identity was Rodolfo Guzman, who as the silver-masked Santo was the most famous figure in Free Fight's 70-year history.

Santo, or Saint, starred in some 50 often-surreal thriller and science fiction films in the 1960s and 1970s as an incorruptible hero who fought zombies, criminals and other evildoers. He died in 1984 but one of his 10 sons fights on as Son of Santo.

Salvador Lutteroth, a fighter in the Mexican Revolution, is credited with organizing and promoting the first Free Fights in the early 1930s.

For wrestling television commentator Alfonso Morales, the success of Free Fight in Mexico is related to its role as a pressure valve in a country beset by poverty.

"This is a spectacle that will never end as long as the necessity exists in this country," he said.

"There are few countries where you find these sudden bursts of action, this hysteria. The Mexican wrestler has show, the magic of the masks and, unlike in the US, the wrestlers are not so muscly. Their strong point is aerial jumps," he said.

Getting up close

Soccer continues to be the most popular sport in Mexico but wrestlers say Free Fight allows them to get close to the public.

"It lets you get in touch with kids and the youth and you get into a character. In soccer you have almost no contact with the public," said wrestler Octagon, a former professional soccer player with first-division club America.

The top-flight wrestlers are well paid, with the headliners charging some US$2,000 each performance and more if they go on tour to Japan, a country that looks to Mexico in wrestling matters.

Despite the macho image of Mexico, women can also take part in Free Fight and there is even a category of homosexual fighters, the Exotics who sport tight shiny suits with flares below the knee.

The Exotics mostly fight among themselves but occasionally confront the mainstream wrestlers.

"The idea when we started this was to stand up and show that we can do what people thought we couldn't do. It was about showing what we were capable of," said gay wrestler Mayflower, who wears a low-necked suit with wide, billowing sleeves.

May 11 to May 18 The original Taichung Railway Station was long thought to have been completely razed. Opening on May 15, 1905, the one-story wooden structure soon outgrew its purpose and was replaced in 1917 by a grandiose, Western-style station. During construction on the third-generation station in 2017, workers discovered the service pit for the original station’s locomotive depot. A year later, a small wooden building on site was determined by historians to be the first stationmaster’s office, built around 1908. With these findings, the Taichung Railway Station Cultural Park now boasts that it has

Wooden houses wedged between concrete, crumbling brick facades with roofs gaping to the sky, and tiled art deco buildings down narrow alleyways: Taichung Central District’s (中區) aging architecture reveals both the allure and reality of the old downtown. From Indigenous settlement to capital under Qing Dynasty rule through to Japanese colonization, Taichung’s Central District holds a long and layered history. The bygone beauty of its streets once earned it the nickname “Little Kyoto.” Since the late eighties, however, the shifting of economic and government centers westward signaled a gradual decline in the area’s evolving fortunes. With the regeneration of the once

In February of this year the Taipei Times reported on the visit of Lienchiang County Commissioner Wang Chung-ming (王忠銘) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a delegation to a lantern festival in Fuzhou’s Mawei District in Fujian Province. “Today, Mawei and Matsu jointly marked the lantern festival,” Wang was quoted as saying, adding that both sides “being of one people,” is a cause for joy. Wang was passing around a common claim of officials of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the PRC’s allies and supporters in Taiwan — KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party — and elsewhere: Taiwan and

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he