On July 16, two days before the opening of Treasures of the Sons of Heaven, (天子之寶) a 400-item exhibition from the National Palace Museum (國立故宮博物院) collection at the Altes Museum in Berlin, government and museum officials were busy fielding questions about the legitimacy of these centuries-old Chinese artifacts.

The questions were raised mostly by German media, such as Der Spiegel and the television network ZDF. Not until the opening ceremony on July 18, when Klaus-Dieter Lehman, president of the Foundation for Prussian Cultural Property, made clear to the public that the artifacts were not looted during the war did the matter come to something like a conclusion.

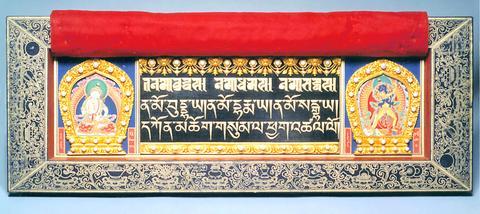

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM

As even Taiwan's cultural exchanges with other countries are seldom free of Chinese attention and sometimes intervention, the museum authorities were afraid that China would try to claim ownership of the collection, though the Chinese government has not done so, so far.

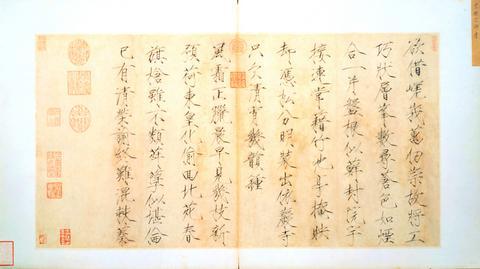

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM

The Palace Museum and Berlin's Altes Museum had been in negotiations for 11 years to secure the exhibition, until the German parliament passed an amendment to the culture preservation law, in 1998. It safeguards the return of on-loan foreign exhibits, preventing the items from being retained in Germany in case of a legal dispute.

Despite assurances that the Taiwanese museum is the rightful owner of the 400 items, as well as its entire collection, Shih Shou-chian (

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM

"If anyone makes a claim on the collection, it will be retained indefinitely until the dispute is solved, which takes several years at least, during which time the collection will be a waste," Shih said.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM

"The last Qing emperor Fu Yi (溥儀) handed over the then Palace Museum collection to the government of the Republic of China during the latter's takeover. At the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War, the government took the best of the collection with it from Nanking to Shanghai, Guizhou to Sichuan, and then back to Nanking after World War II. During the civil war, the government took the collection with it to Taipei. This history shows the collection belongs to the ROC government," Shih said.

The Palace Museum currently has 650,000 items, including some from the then Central Museum in Nanking, plus donations and acquisitions in Taiwan.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM

"On the other hand, there is political reality to consider. We were worried that the Chinese government will try to claim ownership because, as far as they are concerned, there is no Republic of China, thus they consider our collection was stolen from them. But we say we are a sovereign state. We lost everything back then except this collection," Shih said, "The two sides have their respective stances, and we have understand that."

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM

Before the museum's exhibition in the US in 1990 and in France in 1996, it also made sure the two countries had laws to prevent foreign exhibits from being retained in their countries.

As for Taiwan, an article in the "Statutes for the Awarding and Subsidizing Art and Culture" (

A Century of German Genius: Masterpieces from Classicism to Early Modernism, an exchange exhibition from Germany set to show in Taipei next May, was agreed upon after the Palace Museum assured Berlin there were such legal protections, which the latter demanded.

In order for collections to be safely exhibited in more countries, the Palace Museum is working with the Czech Republic and Austria on similar legislation. However, the possibility of cooperation between Taipei and the Beijing Palace Museums in China -- which the two have discussed many times and the international art world looks forward to -- is still slim. Although Chinese exhibits are protected by the statute, China offers no similar guarantee for foreign countries.

Protecting foreign exhibits from legal disputes, Shih said, is a recent trend among museums worldwide in reaction to the rising international debate on the return and protection of cultural property.

"In these days of multiculturalism, many museums that exhibit abroad naturally risk getting into disputes over the origin of artifacts. Most importantly, countries began to ponder the decline of their culture at the end of the 20th century. In this climate, seeing other countries owning artifacts from your country is a head-on shock," Shih said.

The British Museum has not solved its dispute with Greece over its collection of the Elgin Marbles, or the Parthenon sculptures, which Greece claims was stolen. The 56 sculpted friezes were bought by Lord Elgin in 1806 from the Ottoman authorities governing Greece at the time.

Germany still asks for the return of a Russian collection of paintings, books and jewelry the Red Army seized from Germany at the end of the World War II, including a gold diadem, from ancient Troy. The Turkish Government, as the legitimate authority in present-day Troy, has announced in turn that it would claim it from Germany.

Japan still owns tens of thousands of Korean cultural objects, taken from the peninsula during its colonization. Jewish families worldwide have claimed artifacts from museums in Europe and the US, which were taken by Nazi Germany.

The issue is complicated by the different stances of countries and the long span of time.

"The countries that suffer losses think the other party are thieves. The current owner of the artifacts says the artifacts belong not to any country but to the whole of mankind. Their usual argument is that the other country was in a bad condition and was not able to properly protect its cultural heritage, so they saved the items from mishaps.

"Or they say that the other country did not deem them valuable at the time so they were able to buy them cheap. Their attitude is that they are the savior of these artifacts, allowing the whole world to see the cultural treasures now. Nationalism aside, this kind of argument makes sense," Shih said.

This argument similarly applies to the Palace Museum collection. "If these artifacts stayed behind, [after the Communist Revolution] no one knows what would have happened to them. Even from the one perspective of preserving artifacts for all mankind, our ownership of them is beyond doubt. We preserved them well," Shih said.

Here, people have been asking for the return of their family properties in recent years. In 1999, the National Museum of Natural Science (

"It was the first such settlement in Taiwan. As there's no existing law to regulate these matters, we have to judge on a case-by-case basis. We evaluated the financial impact of returning [the item], its cultural and historical value and also the meaning of the tablet for the Yeis. With the tablet back, the family can now worship their ancestors," said Hsu Mei-rong (許美蓉), of the research and exhibition department of the museum.

"From our point of view, however, we still hoped that it would remain at the museum, so that many more people can view this work of ancient culture," Hsu said.

"We also need legislation on the issue to provide museums with some guidelines in handling such problems."

The museum's decision was in part influenced by the example set up by the US Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act, which states that artifacts should be returned to native Americans and the museum may get them on loan when arranging them for exhibitions.

The Pan family properties, which were obtained by the Japanese government in 1933 by unclear means, are now part of the the National Taiwan Museum collection. They are now the subject of an argument between the museum and Pan Hsi-chi (潘稀祺), who asked for its return last month. The museum agreed to work on a settlement with the family.

"On the international level, there is the 1954 Hague Convention to govern the return of cultural properties," said Chen Kuo-nin (

As for the Palace Museum collection, Chen said that any doubt of its legitimacy is unjustified, as it belongs to the ROC.

"If they are illegitimate, then most of the collection in the British Museum and other big museums in Europe and the US are also illegitimate," Chen said.

However, the political reality, or "Taiwan's diplomatic situation," as Shih called it, still makes the legal protection of the exhibits necessary.

"If there ever are claims on exhibits, people will miss the chance to see important cultural treasures Whatever the outcome of any dispute, no one comes out a winner."

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

We have reached the point where, on any given day, it has become shocking if nothing shocking is happening in the news. This is especially true of Taiwan, which is in the crosshairs of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), uniquely vulnerable to events happening in the US and Japan and where domestic politics has turned toxic and self-destructive. There are big forces at play far beyond our ability to control them. Feelings of helplessness are no joke and can lead to serious health issues. It should come as no surprise that a Strategic Market Research report is predicting a Compound