For centuries, the mighty Incan empire has confounded researchers.

The Incas controlled territory up and down the spine of South America, with a sophisticated system of tributes and distribution that kept millions fed through the seasons. They built irrigation systems and stone temples in the clouds.

And yet they had no writing. For scholars, this has been like trying to imagine how the Romans could have administered their vast empire without written Latin.

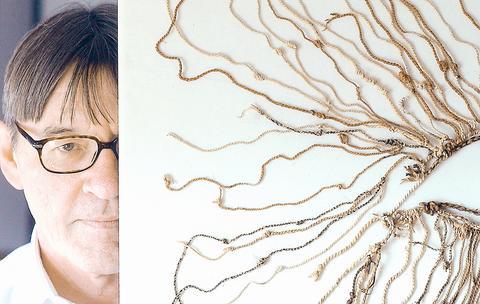

PHOTO: NY TIMES

Now, after more than a decade of fieldwork and research, a professor at Harvard University believes he has uncovered a language of binary code recorded in knotted strings -- a writing system unlike virtually any other.

The strings are found on "khipus," ancient Incan objects that look something like mops. About 600 khipus (also spelled "quipu") survive in museums and private collections, and archeologists have long known that the elaborately knotted strings of some khipus recorded numbers like an abacus. Harvard's Gary Urton said the khipus contain a wealth of overlooked information hidden in their construction details, like the way the knots are tied -- and that these could be the building blocks of a lost writing system which records the history, myths, and poetry of the Incas.

The theory has Incan scholars abuzz. The discovery of true Incan writing would revolutionize their field the same way that deciphering the Egyptian hieroglyphics or Mayan glyphs lifted a veil from those civilizations. But it also has broader interest because the khipus could constitute what is, to Western eyes, a very unorthodox writing system, using knots and strings in three dimensions instead of markings on a flat expanse of paper, clay, or stone.

"What makes this work so interesting is that what is being expressed is being conceptualized in such a different way than we conceptualize," said Sabine MacCormack, a historian of the Romans and the Incas who is a professor at the University of Notre Dame. "This is about an expression of the human mind, the likes of which we don't have elsewhere."

The only way to prove Urton's theory correct would be to translate the khipus, which no one has yet done. In his new book, he proposes a new method for transcribing the knotted strings which he believes could lead to breakthroughs. And his work, funded in part by a genius grant from the MacArthur Foundation, has helped fuel a resurgence of scholarly interest in khipus. Later this month, the Chilean Museum of Pre-Columbian Art in Santiago is opening the world's first exhibit dedicated to the khipu.

"We are on the cusp of a very hot period," said Frank Salomon, a professor of anthropology at the University of Wisconsin who has studied khipus extensively.

The khipu mystery dates to the early 16th century, when the Incas were conquered by Francisco Pizarro and the Spanish set about destroying their culture. The missionaries sent to South America tried to eliminate all touches of the old gods, including the strange stringed textiles that the Incas said held their histories.

The Spanish chroniclers often exaggerated, but they did record histories of tributes and other stories they said were "read" to them by khipukamayuq -- or knot keepers -- from strings of knots.

In 1923, researcher L. Leland Locke was able to show that many khipus recorded numbers like an abacus, with knots in positions representing the hundred's, ten's, or one's place. He concluded that khipus were an accounting tool and scholars largely lost interest.

Locke, however, missed many subtleties in the khipus, which could make them a richer tool for communication, said Urton, whose research was described in a recent issue of the journal Science, and whose new book is called Signs of the Inka Khipu.

The attention to khipus has its roots in insights from Marcia and Robert Ascher, a husband-and-wife team who began an extensive survey and analysis of khipus in 1968, and on the observations of Bill Conklin, a textile specialist at the Textile Museum in Washington, DC, who noticed that khipus were spun and tied in surprisingly complex and varied ways.

Urton is proposing a system for tackling the meaning of the knots. Each knot, Urton suggests, can be thought of as a series of decisions, such as whether to make it of cotton or wool, to tie the knot with a crossing string that begins in the upper left or the upper right, and to use string that is spun clockwise or counterclockwise.

Not all scholars are persuaded by Urton's ideas.

"I don't see that this proposal arises from the actuality of the khipus," said Marcia Ascher, an emerita professor of mathematics at Ithaca College. "I don't see it being shown to fit or explain any of them."

Using money from the National Science Foundation, Urton has undertaken a comprehensive project to record as many khipus as possible in great detail, including the binary information he says could be so important. He hopes to place it all in a single computer database and give access to other scholars and the public in the hopes that somebody will see ways to crack the code. He is being helped by Carrie Brezine, a weaver and database specialist who did her undergraduate thesis in mathematics.

Last week, Brezine brought in a printout of transcriptions taken from khipus found recently in a cave overlooking the Lake of the Condors in northern Peru. As he sat in his office, surrounded by Andean textiles, he noticed long strings of numbers that were virtually identical on three of the khipus -- an indication that information was being copied from one to another, the way medieval scribes copied books by hand.

"It was one of those eureka moments," he said with a boyish grin. "This is really cool."

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by