his weekend an exhibition that looks at the works of the painter and seal carver Lee Da-mu (

Lee was not an artistic luminary such as Chi Pai-shi (

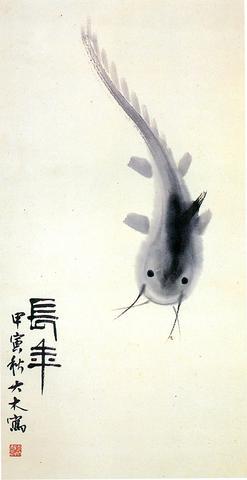

PHOTO COURTESY OF NATIONAL MUSEUM OF HISTORY

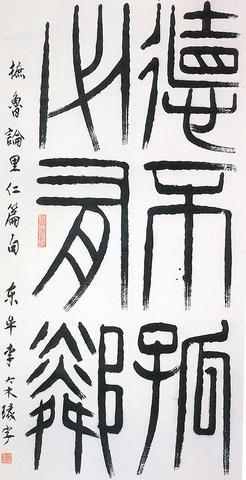

Although not a major artist, Lee was highly regarded as a seal carver in the chuan or seal style script, and a large number of seals carved by him are on display and form a significant part of the show, which spans the whole of his working life.

PHOTO COURTESY OF NATIONAL MUSEUM OF HISTORY

Seal carving is not one of the more easily accessible arts, but the number of specimens on show does help give even a novice some idea of what this somewhat esoteric art form is all about. More importantly, the comprehensiveness of the exhibition, which includes, painting and calligraphy, also shows the relationship between these arts in the work of a single artist.

Paintings, Calligraphy and Seal Carving by Lee Da-mu is primarily an overview of a man who lived life in the modern world, but was still intimately linked with the ancient tradition of the Chinese literati. His lack of fame may partly be due to his conservatism, and while he was not unaffected by the revolutions in Chinese art that took place through the 20th century, his work shows no violent departure from convention.

His artistic shift was the decision to break away from the overpowering influence of Chi Pai-shi, which is expressed in a work titled Crabs in Ink (

Much of this is art as an expression of personality -- as much Chinese literati art has long been -- but Lee's exhibition has an intimacy that is shorn of any hype. While the carvings might only delay casual viewers for a few moments, despite being artistically the valuable part of the show, the paintings, with their bold, sculptural strokes and intricate detail are worthwhile.

Works such as Morning Glory in Ink (

While one might not be familiar with all the subtle expressions of Chinese literati life, the personality that is expressed through the calligraphy and the paintings is strong enough to transcend cultural boundaries. So, even though this is a small exhibition of a relatively minor artist, it is a surprisingly rich offering by the National Museum of History.

What: A Memorial Exhibition: Paintings, Calligraphy and Seal Carving by Lee Da-mu

Where: The National Museum of History

When: Until July 20

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Toward the outside edge of Taichung City, in Wufeng District (霧峰去), sits a sprawling collection of single-story buildings with tiled roofs belonging to the Wufeng Lin (霧峰林家) family, who rose to prominence through success in military, commercial, and artistic endeavors in the 19th century. Most of these buildings have brick walls and tiled roofs in the traditional reddish-brown color, but in the middle is one incongruous property with bright white walls and a black tiled roof: Yipu Garden (頤圃). Purists may scoff at the Japanese-style exterior and its radical departure from the Fujianese architectural style of the surrounding buildings. However, the property