Chang Chien-chi (

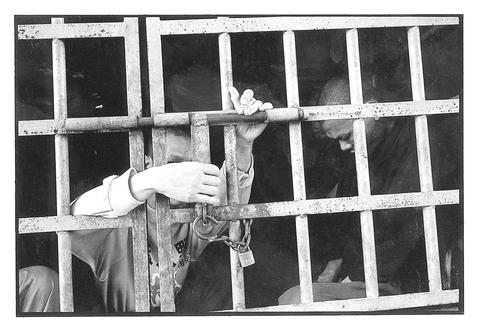

The master printer fastens one of the huge photographs to the wall and the paper unrolls, revealing two men holding hands, a chain locking them together at their waists. Griffin hangs another print. Three women with shaved heads, also chained, are captured in a triptych reminiscent of a grotesque ballet pose.

PHOTO: CHIEN-CHI CHANG/MAGNUM PHOTOS

Forty portraits, which Chang collectively calls The Chain, make up the heart of an exhibition which opens tomorrow at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum. They were taken at a mental care institution called Lungfatang (

PHOTO: CHIEN-CHI CHANG/MAGNUM PHOTOS

"Why do they chain them together?" asks Griffin.

"Usually one is more stable," says Chang.

PHOTO: CHIEN-CHI CHANG/MAGNUM PHOTOS

"That's radical therapy," says Griffin.

PHOTO: CHIEN-CHI CHANG/MAGNUM PHOTOS

Griffin's assistant says that after printing the portraits, he was haunted by the faces, the sores on the feet. "The strange thing is the pictures are really beautiful, too," says Griffin.

A search for truth

Chang began visiting the institution in 1993. In 1998, the inmates were paraded through a warehouse, where they paused in the light from an open door as Chang took a few frames. "Seven years of going back over and over again for pictures that took just 1/25 of a second to capture," says Chang. Looking at the pictures later, Chang decided he had found truth. "Everything is there -- all the information, the emotion."

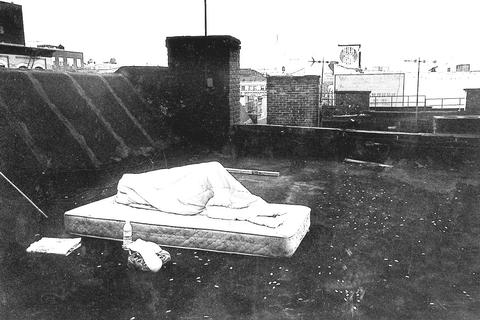

After majoring in English at Soochow University in Taiwan, Chang went to Indiana University in the US, where he took a course in photography and discovered his career. Photographer Eugene Richards had Chang as a workshop student during those early days. "He was a little bit crazed," recalls Richards. "We would find him asleep on the floor in the classroom -- obsessed with photography." One of the things that Richards pushes his students to do, he says, is to examine themselves and their own lives. "We're all afraid to look at ourselves. Most photographers don't," says Richards. "Ultimately, Chien-Chi did."

Not far from Griffin's Chinatown studio is a tenement apartment where some 50 illegal immigrants from Fujian sleep in shifts and wake to work 16-hour days in the garment factories and restaurants of Chinatown, sending what little money they make back to their families. Drawn to people who, like himself, were trying to make their way in a new place, Chang moved into the apartment. The photographs he made there earned him stories in National Geographic and Time magazines, the Missouri Magazine Photographer of the Year award, a first place World Press Photo award and the prestigious W Eugene Smith grant.

A Chinese crowd swirls in the street under an American flag. Men look at snapshots from home or talk on the phone, telephone cords linking them to their homes in China. Mel Rosenthal who teaches photography at Empire State College in New York City, believes it is Chang's own double vision that gives these pictures their richness. "Though he is to some extent an insider, he is looking as an outsider," he says. "His work is always social, cultural, rather than about a single event or individual."

Chang heads off to visit another printer preparing pictures for his exhibit. Not far from Chinatown, Brian Young's Manhattan studio is in a quieter, hipper, New York world of images and art. Chang is equally comfortable here.

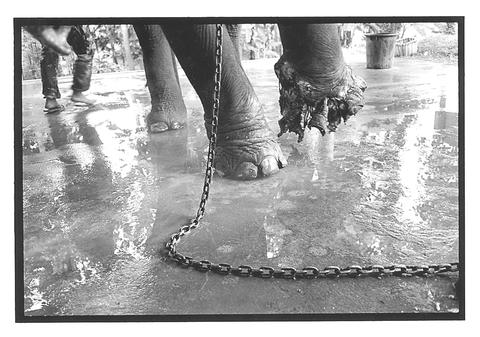

Donning white cotton gloves, Chang fastidiously unrolls the silver gelatin prints. "Every print is different -- the human touch," he says. "I'd never be happy with computer prints." He peers at the surface, blows on the fiber paper to see whether the spot is a speck of dust or an imperfection. The unmistakable shape of an elephant looms amid tropical wilderness, but the elephant is chained. Chang examines the other photographs he took of these animals in Thailand, maimed by land mines, undergoing surgery, dying and dead.

A poet with a camera

Then come the brides. Not a celebratory wedding album but a jaundiced look at the industry and tradition of marriage. A couple is caught in a net of spray-string confetti. A chain of wedding couples kiss in a zoo. Chang, the unwed eldest son with four sisters, admits that the theme of this series was his own internal conflict about marriage. "I had to do something to channel all this traditional family pressure," he says wryly. Perhaps the most evocative photograph is of a post-nuptial couple in the back of a limousine, sound asleep. It is a funny picture, and sad, and one that no one else could have seen in quite the same way.

Those qualities led Chang's photographs to be selected by the exclusive photo agency, Magnum, for its own world tour exhibition. "Magnum has always been built on someone who sees differently, recognizes the quirkiness and incongruities of life," says long-time Magnum photographer Philip Jones Griffiths. "Chien-chi puts something of himself into his pictures, is delighted by what he finds around him. He is a poet with a camera."

The poet is now in the offices of Magnum, where he has been printing recent photographs for Germany's Geo magazine. He travels light, with two Leicas and a few lenses, and his own vision of the world. Those who have watched him shoot say it is hard to tell what he is seeing as he prepares to snap a shot, that it is only later the composition emerges. "Every detail counts," explains Chang.

And so he lays out The Chain on the floor of the photo agency at midnight to order the pictures the way they will appear on the wall of the museum. The pairs of asylum inmates separate and move together, come towards the viewer and retire. "If you look, you will see the invisible chain all the way," says Chang. And if you look, you will see the invisible chain in all of his photographs, the ties to home and bonds of marriage, and in Chang's case, the unbreakable connection to his work. "It's about freedom, I guess," he says.

Performance Note:

What: The Chain -- Photographs by Chang Chien-chi When: Open tomorrow until March 18, 2001; 10am - 6pm Tuesday to Sunday

Where: Taipei Fine Arts Museum (台北市立美術館), 181 Chungshan N. Rd., Sec. 3, Taipei

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.