I drive a 10-year-old gasoline-fueled car. I need to say that up-front because it’s important you know that I have skin in the game of my argument. Like every other oil consumer, I am benefiting from lower prices. Now, it is time to share the windfall — with the government, via higher gasoline taxes. I will happily read your disagreement, but, please, before you e-mail me to question my sanity, hear me out.

Once upon a time, fuel taxes were universally considered good policy. The likes of former US president Ronald Reagan and former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher, hardly tree-hugging liberal politicians, supported them — and hiked them. They were right then, and their successors would be right today: Higher taxes on gas and diesel will help pay for road infrastructure, including the one effort needed to transition to electric-powered vehicles and encourage lower oil demand.

Along the way, however, fuel duties became toxic, another casualty of modern culture-war politics. In part, that is because the cost of gasoline, alongside milk, is one the most visible of modern life. Thus, few politicians have dared increasing fuel taxes. In fact, the opposite has been true, with tax relief offered in many industrialized nations during the period of high prices from 2021 to last year. In the US, the last president to hike the federal gas tax was Bill Clinton. In the UK, the last increase came more than a decade — and six prime ministers — ago.

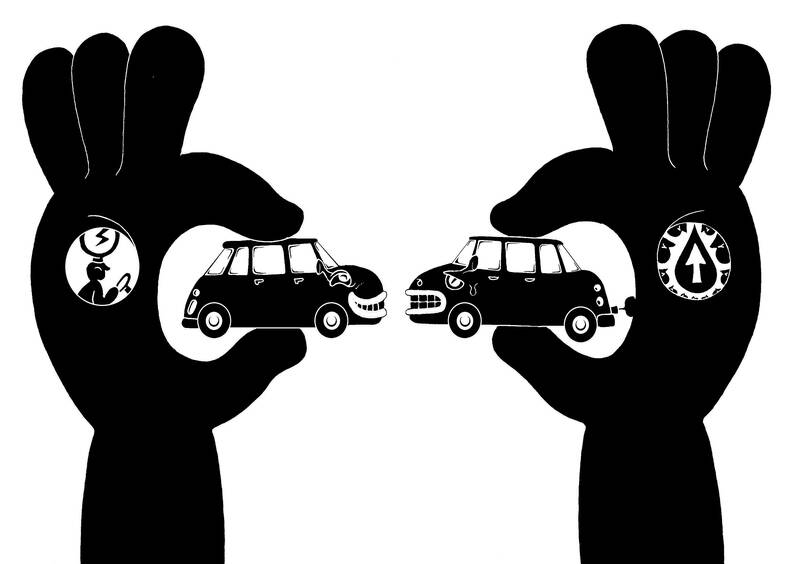

Illustration: Mountain People

Worse, because fuel taxes are not usually indexed with inflation, their purchasing power has plunged. In the US, the tax has been fixed at about US$0.68 per liter since 1993. In real terms, adjusted by the rising cost of living, it is today worth 55 percent less than it was 30 years ago. The same applies to multiple European nations. In the UK, the tax raises less than 1 percent of GDP, compared with more than 2 percent in the 1990s.

The current fall in oil prices creates a window of opportunity. Retail prices have fallen so much (in the US, already 20 percent from a year ago) that policymakers should be able to increase the levy without pushing pump prices too high, thus avoiding a popular backlash. It is not easy, but it is doable. Time is of the essence.

After its campaign to boost prices failed, the OPEC+ oil cartel is counting on a rebound in oil consumption following the current price drop. Western governments should deprive the cartel of that benefit. Unsurprisingly, Saudi Arabia and its oil allies have already started a lobbying campaign against any hikes. OPEC secretary-general Haitham Al Ghais published a commentary entitled “Most of what you pay at the pump is taxes.” The cartel is very aware of the window of opportunity and wants to close up firmly. Do not let it.

I am loathe to tinker with current fuel taxes because they have many time-tested advantages. They establish a direct link between road usage and payment; they collect lots of money; they are simple and cheap to manage; taxpayers largely accept them; and finally, they are difficult to evade. However, perhaps some tweaks could help to ease the potential pain of hikes.

One is to consider an escalator, which hikes the tax when gasoline prices fall below a threshold, but also automatically lowers them if prices rise beyond a point. The biggest pitfall — and, thus, the biggest argument against a hike — is that they are regressive, as with all consumption taxes. Moreover, because wealthier people typically drive newer, more efficient vehicles, the regressiveness is deeper than at first sight. Worse, fuel taxes are, in part, financing the subsidies that wealthy families typically receive in many countries when they switch to electric vehicles.

Another problem is that they are on borrowed time. If the energy transition succeeds, gasoline demand would drop considerably over the next 25 years with greater adoption of tax-free-for-now electric vehicles. The loss of revenue would be a major hit to public finances unless a new tax is developed, this time targeting electric vehicles. Considering the sums involved, it is not too early to start planning.

However, for now, gasoline taxes remain relevant, both as an instrument to manage demand and to raise cash for the public purse. I very much doubt either of the two US presidential candidate — US Vice President Kamala Harris and former US president Donald Trump — would propose a fuel-tax increase in the stretch run of an election campaign.

Neither can I see that happening in France, where the populist Yellow Vest movement started, in part, as a revolt against fuel prices. Or Japan, where the government in Tokyo not only is not raising fuel taxes, but recently extended a direct subsidy on gasoline consumption. However, there is a chance that British Prime Minister Keir Starmer would take the unpopular step when his government unveils the budget next month.

In the UK, where I live, the nationwide average price of unleaded gasoline has fallen to a three-year low of £1.36 (US$1.82) per liter, down nearly 30 percent from a peak of £1.91 per liter in 2022. Starmer has so far showed he is willing to take unpopular steps that are good public policy. He does not face another election for five years. That is a double window of opportunity for him.

Javier Blas is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. He is coauthor of The World for Sale: Money, Power and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

US President Donald Trump created some consternation in Taiwan last week when he told a news conference that a successful trade deal with China would help with “unification.” Although the People’s Republic of China has never ruled Taiwan, Trump’s language struck a raw nerve in Taiwan given his open siding with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggression seeking to “reunify” Ukraine and Russia. On earlier occasions, Trump has criticized Taiwan for “stealing” the US’ chip industry and for relying too much on the US for defense, ominously presaging a weakening of US support for Taiwan. However, further examination of Trump’s remarks in

As strategic tensions escalate across the vast Indo-Pacific region, Taiwan has emerged as more than a potential flashpoint. It is the fulcrum upon which the credibility of the evolving American-led strategy of integrated deterrence now rests. How the US and regional powers like Japan respond to Taiwan’s defense, and how credible the deterrent against Chinese aggression proves to be, will profoundly shape the Indo-Pacific security architecture for years to come. A successful defense of Taiwan through strengthened deterrence in the Indo-Pacific would enhance the credibility of the US-led alliance system and underpin America’s global preeminence, while a failure of integrated deterrence would

It is being said every second day: The ongoing recall campaign in Taiwan — where citizens are trying to collect enough signatures to trigger re-elections for a number of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — is orchestrated by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), or even President William Lai (賴清德) himself. The KMT makes the claim, and foreign media and analysts repeat it. However, they never show any proof — because there is not any. It is alarming how easily academics, journalists and experts toss around claims that amount to accusing a democratic government of conspiracy — without a shred of evidence. These

China on May 23, 1951, imposed the so-called “17-Point Agreement” to formally annex Tibet. In March, China in its 18th White Paper misleadingly said it laid “firm foundations for the region’s human rights cause.” The agreement is invalid in international law, because it was signed under threat. Ngapo Ngawang Jigme, head of the Tibetan delegation sent to China for peace negotiations, was not authorized to sign the agreement on behalf of the Tibetan government and the delegation was made to sign it under duress. After seven decades, Tibet remains intact and there is global outpouring of sympathy for Tibetans. This realization