Pope Francis is making an Asia-Pacific tour that is about more than spreading the word or connecting with the devout. It is a run-through for the ultimate prize the Roman Catholic Church covets: a trip to China.

By some estimates, the world’s second-largest economy is on track to have the biggest population of Christians by 2030. The pope has been keen to engage with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which has historically controlled the appointment of bishops in the country, independent of the Vatican. This has led to worries of a schism, one of the many reasons the pontiff wants to unify China’s Catholics.

His overtures come despite the nation’s worsening track record on religious freedoms. Any future outreach cannot downplay these concerns, or compromise the Vatican’s diplomatic relations with Taiwan, one of the few remaining examples of recognition that the country still has.

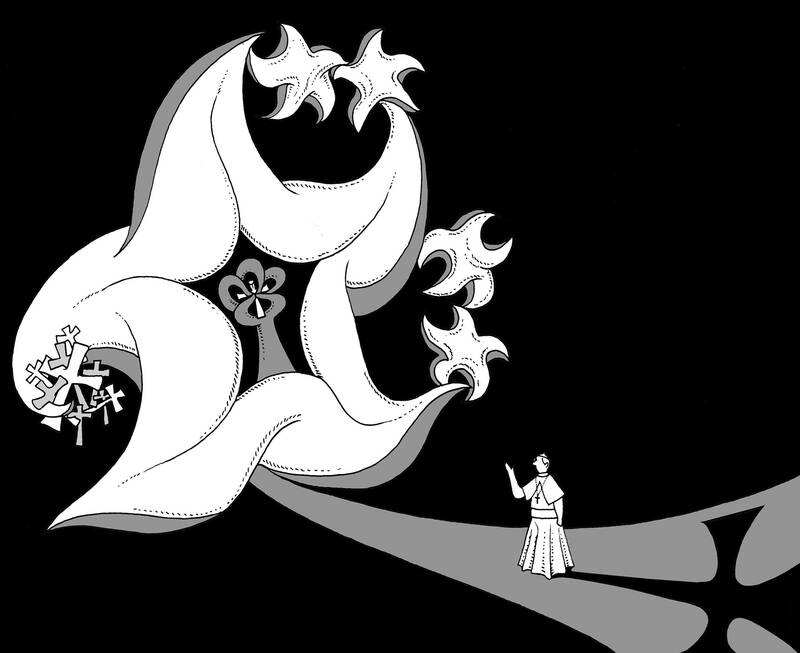

Illustration: Mountain People

No pope has ever visited China, and the Holy See does not have official diplomatic relations with it, despite pursuing closer ties over the past few years. The trip is being viewed as a way to engage with Beijing, but that should not discount the importance of Francis’ current tour to four Asian nations, many of which have sizeable Catholic populations: Indonesia (3 percent, 8 million), Papua New Guinea (26 percent, approximately 3 million), East Timor (97 percent, 1.5 million) and Singapore — home to almost 400,000 Catholics, or 7 percent of the population, many ethnically Chinese — and the last leg of his historic voyage this week.

‘RELIGIOUS FREEDOM’

Still, China is watching very closely. The CCP is officially atheist, and forbids its members from having a religion. However, that dogma has evolved over time and the current constitution, adopted in 1982, states that ordinary citizens enjoy “freedom of religious beliefs.”

What this means in practice, though, is that all faiths are under Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) control. His Sinicization program, introduced in 2015, stipulates religious groups must adapt to socialism, by integrating their beliefs and customs with Chinese culture and political ideology. So in other words, you have the right to worship — but with Chinese characteristics.

“This is not the China of the past, there is no systematic enforcement of atheism now,” said Michel Chambon, research fellow at the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore. “The party is not interested in how you celebrate Mass. Officials just want to ensure that Catholic networks cannot be mobilized against them.”

The relationship between the church and China is complex. Religion was essentially banned during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s, but flourished in the 1980s after the country entered an era of economic reforms. About 2 percent of Chinese adults, or about 20 million people, self-identify with Christianity, the 2018 Chinese General Social Survey showed. Protestants account for roughly 90 percent of those, while the remainder are mostly Catholics.

A 2022 US Department of State report said that there were some 10 million to 12 million Catholics, adding that many have to practice their faith in secret, away from the scrutiny of officials. Those who refuse to join the government’s Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association or pledge allegiance to the party were harassed, detained, disappeared or imprisoned, it said.

Reaching out to the faithful is one reason behind the Vatican’s overtures to China, but it is also about winning hearts and minds among believers divided into two groups: one under a state-controlled church and the other that worships in “underground churches” whose bishops are not approved by Chinese authorities.

The Holy See has been fighting a battle with Beijing about who gets to appoint bishops, and in 2018 reached a compromise — candidates recognized by both would be appointed. For the Vatican, it was a way to bring more Chinese Catholics into the fold, but some high-profile figures in the church, including the now retired Cardinal Joseph Zen (陳日君) of Hong Kong, worried it had ceded too much power.

At the time, Zen told Bloomberg that the pontiff was too optimistic about the Chinese government and warned that closer ties “will have tragic and long-lasting effects, not only for the church in China, but for the whole church.”

His remarks were prescient. In 2022, Zen was fined after being found guilty on a charge relating to his role in a relief fund for Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests in 2019, which he denied.

Taiwan is a pressing dilemma. The Vatican is among 12 diplomatic allies that Taiwan still has left. There are concerns these loyalties could shift, as the Holy See attempts to improve ties with Beijing. Regular meetings between Chinese clergy and their counterparts in Rome, a trend toward normalizing relations, and even discussions about setting up a “stable presence” by the Vatican in China, all point to an upgrading of that relationship.

DUAL RECOGNITION?

Beijing’s efforts to switch international allegiances away from Taipei have been remarkably successful. Getting the Vatican on its side would be a high-profile victory, but the church has consistently maintained that it would never abandon Taipei. It is conceivable, given its religious authority, that it could have spiritual ties with both, and some Taiwanese have even asked the Holy See to press for “dual recognition.”

China will not make that easy, given its animosity toward Taiwan. The Vatican wants to bring all Catholics in China under its umbrella, but that cannot mean a compromise on issues of religious freedom, or a downgrading of its relationship with Taiwan.

The Holy See is Taiwan’s only diplomatic ally in Europe. A pope has never visited there, despite enjoying diplomatic ties for several decades. Casting aside Taiwan for growth in China would seriously damage the church’s credibility as an upholder of spiritual principles.

The Vatican should be transparent about its agreements with Beijing rather than compromise to get deeper access in the country. Consistently voicing concerns about the treatment of the oppressed — a key moral value — should be part of any dialogue with the Communist Party.

As adherence to spirituality declines in the West, growth in the number of faithful will most likely come from Asia. Sacrificing principles for progress is not the way.

Karishma Vaswani is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asia politics with a special focus on China. Previously, she was the BBC’s lead Asia presenter and worked for the BBC across Asia and South Asia for two decades. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

An elderly mother and her daughter were found dead in Kaohsiung after having not been seen for several days, discovered only when a foul odor began to spread and drew neighbors’ attention. There have been many similar cases, but it is particularly troubling that some of the victims were excluded from the social welfare safety net because they did not meet eligibility criteria. According to media reports, the middle-aged daughter had sought help from the local borough warden. Although the warden did step in, many services were unavailable without out-of-pocket payments due to issues with eligibility, leaving the warden’s hands

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi on Monday announced that she would dissolve parliament on Friday. Although the snap election on Feb. 8 might appear to be a domestic affair, it would have real implications for Taiwan and regional security. Whether the Takaichi-led coalition can advance a stronger security policy lies in not just gaining enough seats in parliament to pass legislation, but also in a public mandate to push forward reforms to upgrade the Japanese military. As one of Taiwan’s closest neighbors, a boost in Japan’s defense capabilities would serve as a strong deterrent to China in acting unilaterally in the

Taiwan last week finally reached a trade agreement with the US, reducing tariffs on Taiwanese goods to 15 percent, without stacking them on existing levies, from the 20 percent rate announced by US President Donald Trump’s administration in August last year. Taiwan also became the first country to secure most-favored-nation treatment for semiconductor and related suppliers under Section 232 of the US Trade Expansion Act. In return, Taiwanese chipmakers, electronics manufacturing service providers and other technology companies would invest US$250 billion in the US, while the government would provide credit guarantees of up to US$250 billion to support Taiwanese firms

Indian Ministry of External Affairs spokesman Randhir Jaiswal told a news conference on Jan. 9, in response to China’s latest round of live-fire exercises in the Taiwan Strait: “India has an abiding interest in peace and stability in the region, in view of our trade, economic, people-to-people and maritime interests. We urge all parties to exercise restraint, avoid unilateral actions and resolve issues peacefully without threat or use of force.” The statement set a firm tone at the beginning of the year for India-Taiwan relations, and reflects New Delhi’s recognition of shared interests and the strategic importance of regional stability. While India