Here is the biggest thing happening on our planet as we head into autumn: The Earth is continuing to heat up dramatically. Scientists have said that there is a better than 90 percent chance that this year would top last year as the warmest ever recorded — and paleoclimatologists were pretty sure last year was the hottest in the past 125,000 years. The result is an almost-cliched run of disasters: Open Twitter/X any time for pictures of floods pushing cars through streets somewhere. It is starting to make life on this planet very difficult and in some places impossible. And it is on target to get far, far worse.

Here is the second-biggest thing happening on our planet right now: Finally, finally, renewable energy, mostly from the sun and wind, seems to be reaching some sort of takeoff point. By some calculations, we are now putting up a nuclear plant’s worth of solar panels every day. In California, there are now enough solar farms and wind turbines that day after day this spring and summer they supplied more than 100 percent of the state’s electric needs for long stretches; there are now enough batteries on the grid that they become the biggest source of power after dark. In China it looks as if carbon emissions might have peaked — they are six years ahead of schedule on the effort to build out renewables.

And here is the third-biggest thing in the months ahead: the US presidential election, which looks as if it is going down to the wire — and which might have the power to determine how high the temperature goes and how fast we turn to clean power.

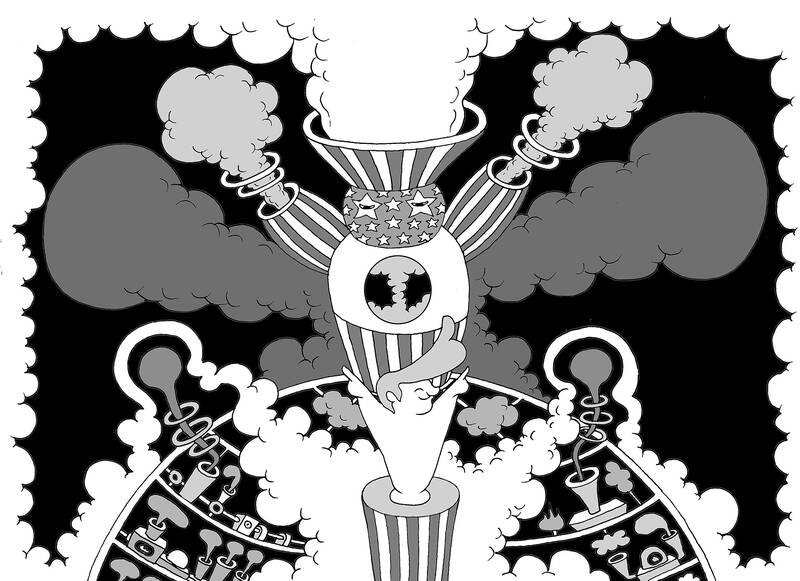

Illustration: Mountain People

Former US president Donald Trump gave an interview late last month, in which he laid out his understanding of climate change:

“You know, when I hear these poor fools talking about global warming. They don’t call it that any more, they call it climate change because you know, some parts of the planet are cooling and warming, and it didn’t work. So they finally got it right, they just call it climate change. They used to call it global warming. You know, years ago they used to call it global cooling. In the 1920s they thought the planet was going to freeze. Now they think the planet’s going to burn up. And we’re still waiting for the 12 years. You know we’re down almost to the end of the 12-year period, you understand that, where these lunatics that know nothing, they weren’t even good students at school, they didn’t even study it, they predict, they said we have 12 years to live. And people didn’t have babies because they said — it’s so crazy. But the problem isn’t the fact that the oceans in 500 years will raise a quarter of an inch, the problem is nuclear weapons. It’s nuclear warming... These poor fools talk about global warming all the time, you know the planet’s going to global warm to a point where the oceans will rise an eighth of an inch in 355 years, you know, they have no idea what’s going to happen. It’s weather.”

I have quoted this at length, because this could again be the most important man on the planet, talking about the most important issue the planet has ever faced And he has gotten every word of it wrong. It is gibberish.

However, it is gibberish in the service of something very important and very dangerous: doing all that he can to block the energy transition, in the US and around the world. His friends at Project 2025 have laid out in considerable detail how you translate that gibberish into policy. It lays out in loving detail many of the steps his administration would use to bolster oil, gas and coal, while sidetracking sun and wind. These include ending the effort to spur electric vehicle production in Detroit; ending support for renewables (Trump has promised to “kill wind,” whatever that means); and reversing a crucial 2009 finding from the Environmental Protection Agency that carbon dioxide causes harm, a position that undergirds much of the federal effort to rein in climate pollution. He has also — chef’s kiss — promised to close down the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, otherwise known as the people who measure how much the temperature is rising. That is on the grounds that those measurements are “one of the main drivers of the climate change alarm industry.”

In return for this endless largesse (beginning on day one, Trump said, he would become a dictator in order to “drill, baby, drill”), he has asked the industry for only (Austin Powers moment here) “1 billion dollars” in campaign contributions. Big oil is doing its best. As the Washington Post reported a couple of weeks ago, Harold Hamm, one of the nation’s most prominent frackers, is working the phones to come up with as much cash as possible.

Hamm is working “incredibly hard to raise as much money as he can from the energy sector,” a Trump campaign aide said. “We’ve gotten max-out checks from people we’ve never gotten a dollar from before.”

Can Trump reverse the tide toward renewable energy? No, not entirely — it is too strong, based on the ever-falling cost of sun, wind and batteries. Even in Texas — headquarters of the hydrocarbon cartel where the state legislature has tried to pass laws limiting renewables — the undeniable economics of clean power continues to surge. The Lone Star state is now leading the nation in installing batteries on its grid, a good thing given the ongoing spate of climate disasters that strain and stress the state’s system.

However, he can slow it down considerably. The US’ buildout of renewables is dependent, among other things, on overcoming the bewildering array of permitting requirements that make every transmission line a harrowing bureaucratic battle. At the moment, the Joe Biden-Kamala Harris White House has a dedicated team at work, with senior officials assigned to senior projects, constantly bird-dogging them to make sure that they get built on schedule. That would disappear, replaced with a new set of bureaucrats deeply invested in making sure these projects did not happen.

At least as bad would be the effect around the world. Last time, Trump the US from the Paris climate accords, badly denting the momentum those talks had produced. This time he would do the same and more — he has promised, for instance, to end Biden’s pause on liquefied natural gas export terminals. These are designed to take huge volumes of US gas and ship it to Asia, where it wpi;d undercut the move to renewables. It is the last real growth strategy the oil industry has, and it is the biggest greenhouse gas bomb on the planet.

In essence, Trump would give every other oligarch in the world — Russian President Vladimir Putin, the king of Saudi Arabia and on down the list — license to keep pumping away. If the biggest historical emitter of greenhouse gases is not going to play a role, why should anyone else feel any pressure? As Project 2025 quite clearly declares, Trump would “rescind all climate policies from its foreign aid programs” and “cease its war on fossil fuels in the developing world.” (although Trump has claimed not to know anything about Project 2025.) The global climate talks in Brazil next year and the 2026 version in Australia — currently shaping up to be the last huge chance for global cooperation — would be turned on their heads.

There are ways to calculate the meaning of all this. The UK-based non-governmental organization Carbon Brief, for instance, said earlier this year that “a victory for Donald Trump in November’s presidential election could lead to an additional 4 billion tonnes of US emissions by 2030 compared with Joe Biden’s plans.” Just for perspective, that is a lot: “This extra 4 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) by 2030 would cause global climate damages worth more than US$900 billion, based on the latest US government valuations. For context, 4GtCO2e is equivalent to the combined annual emissions of the EU and Japan, or the combined annual total of the world’s 140 lowest-emitting countries.” It is like finding an extra continent full of greenhouse gases.

But worse than the totals is the timing. If a Trump administration was merely going to be a four-year interregnum, it would be annoying. However, it comes at precisely the moment when we need, desperately, acceleration. We are on the edge of breaking the planet’s climate system — we can see it cracking in the poles (the Thwaites glacier now undermined by warm seawater), in the Atlantic (the great currents now starting to slow) and in the Amazon (where savannafication seems to be gathering speed). The earth’s hydrological system — how water moves around the Earth — has already gone kaflooey, as warm air holds far more water vapor than cold.

The world’s climate scientists have done their best to set out a timetable: cut emissions in half by 2030 or see the possibilities of anything like the Paris pathway, holding temperature increases to 1.5°C above preindustrial levels, disappear. That cut is on the bleeding edge of the technically possible, but only if everyone is acting in good faith. And the next presidential term will end in January of 2029, which is 11 months before 2030.

If we elect Donald Trump, we might feel the effects not for years, and not for a generation. We might read our mistake in the geological record a million years hence. This one really counts.

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them

More than 30 years ago when I immigrated to the US, applied for citizenship and took the 100-question civics test, the one part of the naturalization process that left the deepest impression on me was one question on the N-400 form, which asked: “Have you ever been a member of, involved in or in any way associated with any communist or totalitarian party anywhere in the world?” Answering “yes” could lead to the rejection of your application. Some people might try their luck and lie, but if exposed, the consequences could be much worse — a person could be fined,

Xiaomi Corp founder Lei Jun (雷軍) on May 22 made a high-profile announcement, giving online viewers a sneak peek at the company’s first 3-nanometer mobile processor — the Xring O1 chip — and saying it is a breakthrough in China’s chip design history. Although Xiaomi might be capable of designing chips, it lacks the ability to manufacture them. No matter how beautifully planned the blueprints are, if they cannot be mass-produced, they are nothing more than drawings on paper. The truth is that China’s chipmaking efforts are still heavily reliant on the free world — particularly on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

Last week, Nvidia chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) unveiled the location of Nvidia’s new Taipei headquarters and announced plans to build the world’s first large-scale artificial intelligence (AI) supercomputer in Taiwan. In Taipei, Huang’s announcement was welcomed as a milestone for Taiwan’s tech industry. However, beneath the excitement lies a significant question: Can Taiwan’s electricity infrastructure, especially its renewable energy supply, keep up with growing demand from AI chipmaking? Despite its leadership in digital hardware, Taiwan lags behind in renewable energy adoption. Moreover, the electricity grid is already experiencing supply shortages. As Taiwan’s role in AI manufacturing expands, it is critical that