A university in Britain has never gone bankrupt, which is quite a record for a sector with more than 900 years of history. The day might not be too far away, if the sounds of distress emanating from the halls of academia are anything to go by. The head of the largest higher-education union has called for an emergency rescue package to stave off “catastrophe.” The crunch should surprise nobody. This was a crisis foretold.

A succession of reports has warned of the precarious funding structure underpinning UK universities. Tuition fees for domestic students have been held at £9,250 (US$11,759) since 2017, and have been increased by only £250 in the past 12 years. They are now worth less than £6,000 in 2012 prices. Without the rich endowments that backstop US universities or other significant sources of income, British institutions have turned to international students, who pay far higher fees. Their dependence on this lucrative revenue stream has increased as the numbers surged. Once growth turned to shrinkage, a reckoning was inevitable.

About 40 percent of higher-education providers, or 108 out of 269, expected to be in deficit in the university financial year that ended on Wednesday, according to a May financial-sustainability report by the Office for Students, which regulates the sector in the UK.

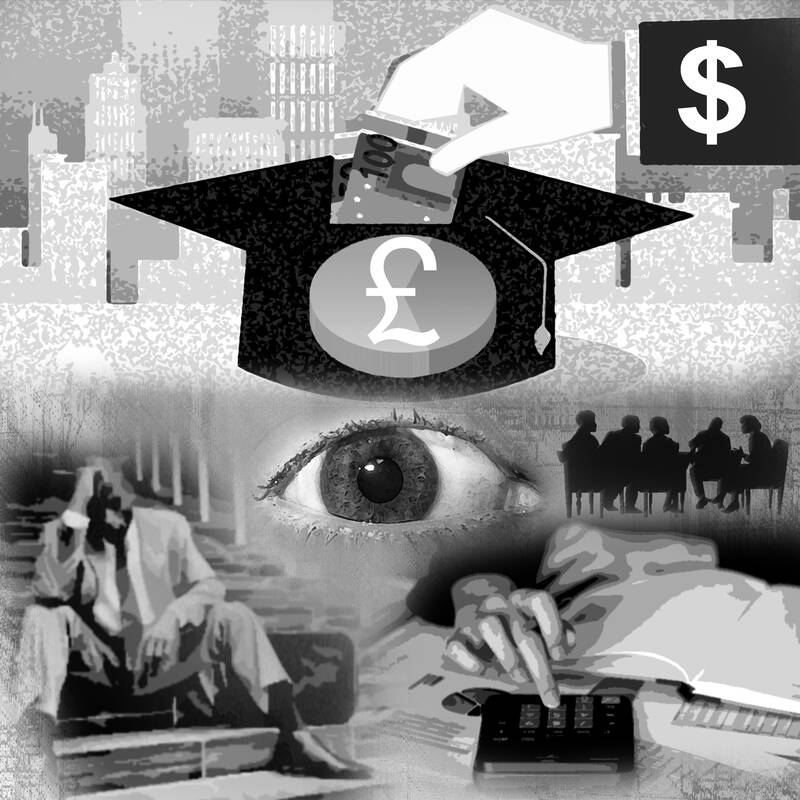

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

That is before they feel the full effect of the decline in international recruitment. The word “challenging” appears 13 times in the study.

The report modeled a series of gloomier scenarios than the forecasts provided by universities, which it described as too optimistic. In the bleakest, overseas entrants were seen dropping 61 percent by the 2026-2027 academic year compared with last academic year. That would reduce the sector’s annual net income by a cool £9.7 billion and push 226 institutions, or 84 percent of the total, into deficit. Even in the mildest scenario, which posited no growth in overall student numbers through 2026-2027, net income was seen falling £3.4 billion with 176 providers sinking into deficit.

How likely is such a contraction? It is not beyond the bounds of possibility. A 60 percent drop would take the overseas student intake only back to the about 200,000-a-year numbers they were running at between 2012 and 2018. A 45 percent reduction in the coming academic year “appears to be realistic” based on recent recruitment data, the report said.

They might yet settle at a higher level. The latest British Home Office statistics for student visa applications show a 17 percent decline in the six months through June from a year earlier. The peak season for applications is from last month to next month, so a fuller assessment would have to wait until later in the year.

Even if a late pickup in overseas demand provides a stay of execution, it does not change the overall picture of a funding model that has reached its sell-by date. Growth in higher-paying international students has papered over the shortfall in revenue at the cost of social strains, with domestic applicants increasingly feeling squeezed out of the most competitive courses at the most desirable universities. The system would soon have to absorb a much larger cohort of UK students: A demographic bulge means there would be 200,000 more 18-year-olds in 2030 than in 2020.

The Labour government that took office last month has rejected the appeal for a bailout from Jo Grady, general secretary of the University and College Union, which represents 120,000 sector employees. A university financial crisis is the last thing Labour needs, with so many other claims on the public purse. Dozens of institutions are already planning or implementing staff and course cuts to reduce costs — Lincoln, Huddersfield, Goldsmiths in London and Kent among them, some reports in the British media said.

The majority of the sector “is in trouble,” said Vivienne Stern, chief executive officer of Universities UK, which represents 142 institutions.

The failure of a major institution would test the British government’s resolve to have the sector sort out its own problems. Higher education is a significant economic contributor and source of competitive advantage for Britain, with a worldwide reputation for quality that fuels export earnings and burnishes the country’s prestige. The sector supported 768,000 full-time jobs and generated economic output of more than £130 billion in the academic year ending in 2022, a study by London Economics showed.

Fundamental change to the financing structure looks inevitable. At some stage, domestic tuition fees would surely need to be reset and indexed to inflation — as unpalatable as that choice might be, given the already high levels of UK student debt. There might also be a case for differentiating fees to reflect their cost of delivery and future value to undergraduates, King’s College London vice chancellor Shitij Kapur said.

A nurse and a dentist who graduate in England pay essentially the same for their education — even though the cost of educating the latter is much greater, Kapur wrote in a study that was published in November last year.

In the meantime, expect more retrenchment, consolidation of courses and even mergers. Sharing administrative functions such as finance, human resources and technology is an obvious cost-saving route for institutions that are geographically close to each other. This process is just getting started.

If you have children likely to enter university in the next few years, get ready to pay more.

Matthew Brooker is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business and infrastructure. Formerly, he was an editor for Bloomberg News and the South China Morning Post. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Taiwan has lost Trump. Or so a former State Department official and lobbyist would have us believe. Writing for online outlet Domino Theory in an article titled “How Taiwan lost Trump,” Christian Whiton provides a litany of reasons that the William Lai (賴清德) and Donald Trump administrations have supposedly fallen out — and it’s all Lai’s fault. Although many of Whiton’s claims are misleading or ill-informed, the article is helpfully, if unintentionally, revealing of a key aspect of the MAGA worldview. Whiton complains of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party’s “inability to understand and relate to the New Right in America.” Many

US lobbyist Christian Whiton has published an update to his article, “How Taiwan Lost Trump,” discussed on the editorial page on Sunday. His new article, titled “What Taiwan Should Do” refers to the three articles published in the Taipei Times, saying that none had offered a solution to the problems he identified. That is fair. The articles pushed back on points Whiton made that were felt partisan, misdirected or uninformed; in this response, he offers solutions of his own. While many are on point and he would find no disagreement here, the nuances of the political and historical complexities in

Taiwan is to hold a referendum on Saturday next week to decide whether the Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant, which was shut down in May after 40 years of service, should restart operations for as long as another 20 years. The referendum was proposed by the opposition Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and passed in the legislature with support from the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). Its question reads: “Do you agree that the Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant should continue operations upon approval by the competent authority and confirmation that there are no safety concerns?” Supporters of the proposal argue that nuclear power

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) earlier this month raised its travel alert for China’s Guangdong Province to Level 2 “Alert,” advising travelers to take enhanced precautions amid a chikungunya outbreak in the region. More than 8,000 cases have been reported in the province since June. Chikungunya is caused by the chikungunya virus and transmitted to humans through bites from infected mosquitoes, most commonly Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. These species thrive in warm, humid climates and are also major vectors for dengue, Zika and yellow fever. The disease is characterized by high fever and severe, often incapacitating joint pain.