By fostering the discovery of truth, philosophy can provide the intellectual foundation for development and illuminate paths toward more cohesive and prosperous societies.

As Victor Hugo put it: “Philosophy should be an energy; it should find its aim and its effect in the amelioration of mankind.”

However, policymakers across Africa have overwhelmingly failed to emphasize this disposition. Rather than developing a collective consciousness that would help foster economic convergence and regional integration, most governments on the continent find themselves managing crisis after crisis. The stickiness of the colonial development model of resource extraction — which is fundamentally disconnected from Africa’s historical traditions and future aspirations — has only exacerbated the problem.

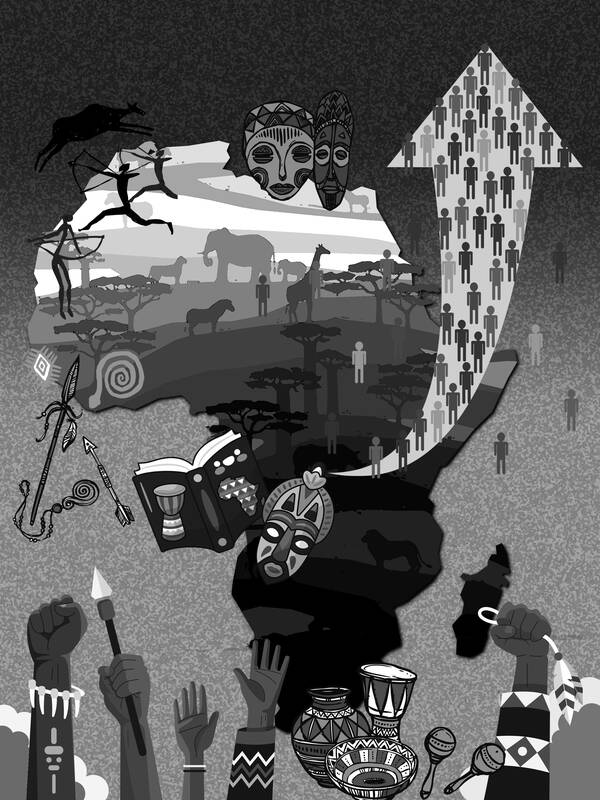

Illustration: Louise Ting

The neglect of philosophy and the resulting ideological vacuum (especially in the policy arena), is also rooted in centuries of colonialism and slavery. The dehumanization of Africans and the repression of their culture became integral to economic prosperity and wealth accumulation in Europe and the US. It involved the systematic destruction of the social structures that defined African societies and held its communities together, reflected today in chronically low trust in the state.

Colonial institutions also caused long-lasting psychological damage to Africans. They turned the descendants of great inventors — including the architects of the pyramids in Egypt and Sudan; the mathematicians who carved the Ishango and Lebombo bones; and the engineers, sailors and navigators who constructed longboats capable of reaching South America and China as early as the 13th century — into passive victims.

Colonialism made cultural discontinuity inevitable. Colonizers plundered and destroyed symbols of artistic, historical and spiritual significance.

Nearly all of Africa’s material cultural legacy is located outside the continent, with Belgium alone possessing more than 180,000 African artworks, recent estimates showed. The looted artifacts range from manuscripts and musical instruments, to palace doors and thrones, wooden statues and ivory masks. The famed Benin Bronzes, which Nigeria has been trying to repatriate for decades, are scattered all over the world, including at Harvard University’s Peabody Museum.

Africans and African states were robbed of the spiritual anchors that shaped their collective imagination and shared history, and that would have promoted social cohesion and cultural continuity across generations.

Museums with looted art are a part of “a system of appropriation and alienation” that continues to strip Africans of the “spiritual nourishment that is the foundation of [their] humanity,” said the authors of a widely praised 2018 report on the restitution of African cultural goods commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron.

Such spiritual starvation perpetuates the colonial development model of resource extraction that helped cause it. The model’s persistence has turned resource-rich Africa into the world’s poorest and most aid-dependent continent, and prevented it from developing meaningful manufacturing industries, which have been consistently shown to expand economic opportunities for workers and enhance global convergence. This set the stage for recurrent balance of payment crises and intergenerational poverty in Africa.

More than any other continent, Africa has been governed by political and economic models that do not reflect its own traditions and that have stifled development by widening the gap between the ingenious past and insipient present, as well as between actual and potential growth. It has also marginalized the continent in the progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals and global efforts to eradicate poverty. Tellingly, Africa is home to nearly 60 percent of the world’s extreme poor, despite accounting for less than 18 percent of its population.

Achieving political independence would be easier than freeing oneself from the colonial mentality, Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o said in his 1986 book Decolonizing the Mind. Thiong’o was right: more than six decades after many African countries won independence, decolonizing minds remains a challenge. The overwhelming majority of Africa’s population is still yearning for spiritual nourishment.

Repatriating looted African artifacts is an important first step, but it must be accompanied by the rebuilding of the physical and institutional infrastructure that preserved symbols of African identity and temporality for centuries before the colonial onslaught. This would help people recover the thread of an interrupted memory and reclaim African history, while increasing the potential for social transformation. In particular, reforming the education system to reflect the continent’s shared history and philosophical foundations could reshape contemporary African life.

The goal should be to create a shared superstructure that enhances continental coordination and strengthens the foundation of trust. This would ensure that individuals, businesses and states can overcome the colonial mindset and foster a new collective imagination and development vision that is authentically African.

The African Continental Free Trade Area, which establishes a single market, is crucial to surmount the imaginary yet significant walls that have been erected between countries. However, more should be done to reduce the short-term risks of competing priorities — balance of payments constraints always seem to trump long-term strategy — and to speak with one voice. Fostering a collective African consciousness at this critical juncture would enable the continent to take advantage of economies of scale and demographic tailwinds to emerge as a major geopolitical player on the world stage.

Absent a strong ideological foundation in the post-independence era, African countries have long embraced development models and ideas that are rooted in the colonial system of exploitation and cultural repression. These models have trapped them in a vicious cycle of intergenerational poverty and aid dependency, and are now exacerbating the volatility and magnitude of shocks caused by climate change and intensifying migration pressures.

Africa’s future hinges on its ability to transcend colonial constructs, leverage its rich cultural heritage, renew African dignity, and embrace development models grounded in Afrocentric philosophical and historical realities.

In the words of the martyred anti-apartheid leader Steve Biko: “It is better to die for an idea that will live than live for an idea that will die.”

Hippolyte Fofack, former chief economist and director of research at the African Export-Import Bank, is a Parker fellow with the SDSN at Columbia University, a research associate at the Harvard University Center for African Studies, a distinguished fellow at the Global Federation of Competitiveness Councils and a fellow at the African Academy of Sciences.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That

On the eve of the 80th anniversary of Victory in Europe (VE) Day, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) made a statement that provoked unprecedented repudiations among the European diplomats in Taipei. Chu said during a KMT Central Standing Committee meeting that what President William Lai (賴清德) has been doing to the opposition is equivalent to what Adolf Hitler did in Nazi Germany, referencing ongoing investigations into the KMT’s alleged forgery of signatures used in recall petitions against Democratic Progressive Party legislators. In response, the German Institute Taipei posted a statement to express its “deep disappointment and concern”