In the summer of 2020, European leaders convened marathon talks over how to rescue a continent battered by the COVID-19 pandemic and a lost decade of economic stagnation. Four days of wrangling between north and south, east and west ensued.

“We were like zombies by the end,” one official said.

However, it ultimately succeeded. The 750 billion euros (US$816 billion at the current exchange rate) rescue fund was not just big, but the kind of unprecedented “Hamiltonian leap” toward unity that could only have come about in a crisis.

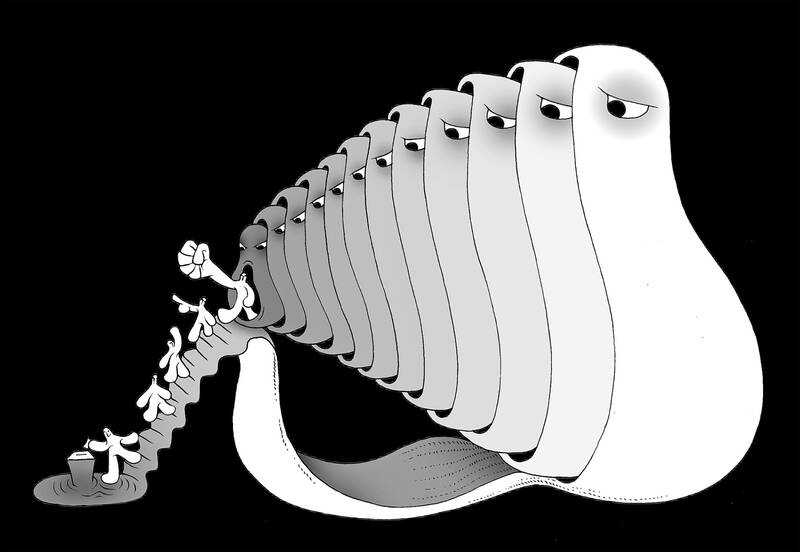

Illustration: Mountain People

Four years on, that spirit seems to have gone missing, as 450 million voters prepare to take part in EU parliamentary elections that could see a surge in support for the far right. The economy has dodged recession, but has struggled to reach the velocity needed to restore confidence at a time of stretched public finances. The scars of the inflation shock, which has undermined the social contract, are still visible. Geopolitical risks abound, with the US and China exerting economic pressure and war raging in Ukraine.

The economy is not the only driver pushing voters into the arms of National Rally leader Marine Le Pen in France or Party for Freedom leader Geert Wilders in the Netherlands; after all, eurozone unemployment is half where it was a decade ago, and no one since Brexit has talked about leaving the union. However, priorities do show rising anxiety.

Supporting the economy and job creation had risen to No. 3 on voters’ priority list, replacing climate change, a Eurobarometer survey found earlier this year.

The energy shock has probably contributed to that: 45 percent of those polled said their living standards had decreased over the past five years — especially those who already had difficulties paying bills — and 49 percent said they had stayed the same.

With old north-south divides threatening to return, as new rules on curbing debt and deficits loom, it feels like a European identity crisis — the sense of a model that is running out of road — is preying on the body politic. A posse of newly elected nationalists, while not an existential threat, would surely be a distraction. The risk of another lost decade is high if the EU spends the next few years bickering internally instead of lifting barriers to investment, innovation and regional security.

“Europe has everything it needs to win the 2020s,” investment firm TPW Advisory founder Jay Pelosky said, citing the region’s current push to ramp up in artificial intelligence, defense and green industry. “But whether it does or not will be decided in the next two years.”

Europe does indeed still have a lot going for it. It has big global companies like LVMH SE, Novo Nordisk A/S and ASML Holding NV. Life expectancy is higher than in the US and income inequality is lower; Europe’s welfare policies are also more generous. The focus on stability and cohesion as pillars of the so-called “European way of life” — a phrase that admittedly rings more hollow since the return of war on the EU’s doorstep — has been a game changer for new members joining in the east, whose per capita income has converged toward the average over the past two decades.

Those frustrating and slow-moving EU processes that demand consensus and coalition building among 27 nations — even in the heat of the pandemic — also have the advantage of boxing in political extremes. Today’s far-right firebrands, by and large, are operating within the democratic system and have dropped some of their most toxic policies (like quitting the EU).

However, stability and cohesion also need growth, and that is where things get messy. It is clear that the economic change since 2019 in the eurozone has fallen a little short of the Hamiltonian leap. GDP is only slightly above where it was going into the pandemic, and that is mainly thanks to state support; private consumption is flat, and capital expenditure below-par. Sure, jobs have boomed and wages have grown, but inflation offset those gains until only very recently.

When it comes to growth, there is no one silver bullet. Productivity and innovation were lagging well before COVID-19, especially when compared with the US, which has been a source of admiration and envy for those trying to build a more integrated, powerful EU. China’s rise as a trade competitor was also apparent well before its overperformance in electric vehicle exports, which threatens one of the traditional ventricles of European growth.

As the world deglobalizes and breaks into regions, it is no longer easy to keep faith in Europe’s single market as a reliable, German-led economic engine, converting cheap energy from Russia into manufactured goods exported to China.

Economist Andre Sapir, who in 2003 authored a report laying out how Europe should fix its innovation and growth lag, said that the problems plaguing the EU today appear much the same: Europe punches below its weight in tech companies, research spending and financing.

What has changed is the geopolitical calculus — and, unfortunately, the appeal of populist parties promising easy solutions, he said over coffee in Brussels.

Change is needed, but Sapir said he fears it would come “slowly and chaotically.”

One promising blueprint for a more dynamic EU is due to hit policymakers’ desks soon. Former Italian prime minister Mario Draghi, credited with saving the euro a decade ago as Greece teetered, is set to publish a report on improving EU competitiveness. It is likely to amplify his recent calls for more investment to reduce Europe’s dependencies in energy, tech and defense, and more spending cooperation at the EU level. It would be a return to the Hamiltonian mentality seen during that summer in 2020, rather than the austerity mindset of the 2010s.

The obvious challenge is how to push more European integration at a time when Paris and Berlin are pushing conflicting agendas and when the likes of Le Pen are promoting a less supranational “Europe of nations.” One answer would be to start with the low hanging fruit: defense. If there is one thing a more right-leaning European parliament can agree on, it is the need to invest in defense and security. A 100 billion euros pan-European defense fund looks like a no-brainer, even if this is a highly sensitive area that national governments would understandably want to keep control of.

Meanwhile, the US’ Inflation Reduction Act, which has hoovered up green investment and jobs from Europe, has yet to see a proper response in the EU — largely because the bloc’s own green subsidies are doled out at the national level. A common EU-wide funding mechanism to ramp up investment would also be a game changer. Other avenues to integration like cutting red tape, capital markets union and a more interconnected electricity market are promising, if not exactly exciting for the average voter.

Europe’s model is worth defending, and most of its problems are fixable. However, time is running out. COVID-19 recovery funding has a time limit of 2026, while new fiscal rules would be fully implemented in 2027. Politically, a lot could also change: Donald Trump could be elected US president. Germans are to vote in national elections next year; the French would vote in a presidential election in 2027 that Le Pen could very well win.

“Wake up,” embattled French President Emmanuel Macron said to voters last week.

The next time crisis leads to a four-day negotiating summit in Brussels, the outcome could be more stumble than leap.

With assistance from Elaine He

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist writing about the future of money and the future of Europe. Previously, he was a reporter for Reuters and Forbes.

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

As the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) races toward its 2027 modernization goals, most analysts fixate on ship counts, missile ranges and artificial intelligence. Those metrics matter — but they obscure a deeper vulnerability. The true future of the PLA, and by extension Taiwan’s security, might hinge less on hardware than on whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can preserve ideological loyalty inside its own armed forces. Iran’s 1979 revolution demonstrated how even a technologically advanced military can collapse when the social environment surrounding it shifts. That lesson has renewed relevance as fresh unrest shakes Iran today — and it should

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged