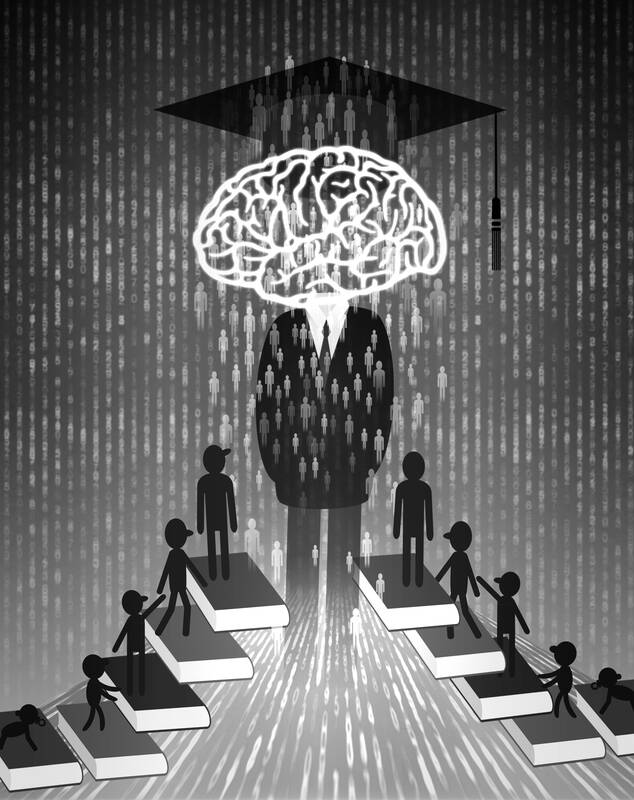

Artificial intelligence (AI) has persuaded a lot of folks that we need to radically overhaul education.

Now that chatbots can speedily retrieve information and answer complex questions, why bother memorizing historical facts or quotations? Should we not instead teach kids to think critically and solve problems, and leave the grunt work to computers?

There is a problem with these arguments: Humans require knowledge to think creatively. Outsourcing our memory and cognition to Google and AI risks making us dumber and more susceptible to misinformation — including errors made by AI.

Illustration: Yusha

I am no Luddite. I think it is amazing that we have a so much information on tap thanks to the Internet, while ChatGPT and other bots can act as personal tutors, which, if used judiciously, might reinforce knowledge by answering all our questions.

I also get why people might think this has devalued the ability to recite a Shakespeare sonnet or the periodic table — or studying for the bar or Chartered Financial Analyst exam, for that matter — and the important thing is knowing where to find information.

However, being able to recall facts is indispensable in the age of search engines and large language models, and I am not alone in believing this.

In a seminal essay published in 2000, two years after Google was founded, nonagenarian US educator E. D. Hirsch demolished the argument that we can always just look things up.

“There is a consensus in cognitive psychology that it takes knowledge to gain knowledge,” he wrote. “Yes, the internet has placed a wealth of information at our fingertips. But to be able to use that information … we must already possess a storehouse of knowledge.”

Hirsch’s ideas inspired the Conservative government to overhaul English education system over the past 14 years to promote a more “knowledge-rich” curriculum: For example, by the age of nine, math pupils are now required to memorize their multiplication tables up to 12.

One cannot ignore the possibility that a Conservative government responsible for a hard Brexit might be wrongheaded about rote learning too — although England’s relative improvement in international education rankings suggests otherwise.

One can certainly debate what kinds of facts kids should have to memorize.

However, Hirsch’s essential point that general knowledge provides a kind of “mental scaffolding” and makes us smarter and better citizens seems self-evident, prior knowledge helps us absorb more of what we learn and provides the fuel for creative thinking.

“The ability to ‘just Google it’ is highly dependent on what a person has stored in their long-term memory,” the influential former British minister of state for schools Nick Gibb said in a 2021 speech.

This means literacy and numeracy remain vital even now that computers can do math and write texts faster than we can.

The suggestion we should outsource our memory to “free up” limited space for more creative thinking is based on a misconception, Nicholas Carr wrote in The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains.

Thanks to its plasticity, the brain’s long-term memory center can expand, as scientists found when they studied London taxi drivers.

“When we start using the Web as a substitute for personal memory, bypassing the inner processes of consolidation, we risk emptying our minds of their riches,” Carr wrote.

Becoming reliant on the Internet or AI is a bad idea because our working memories are only capable of processing a few new items at a time, Daisy Christodoulou, the author of Seven Myths About Education, said in an essay.

So if we encounter too much new vocabulary or information, we become overwhelmed, impairing our ability to learn.

Indeed, looking stuff up on Google often results in us not being able to recall it later — either because our brains are conditioned to think we do not need to remember it, or because the Internet, mobile phones and social media scatter our attention, or both. We are also likely to overestimate our intelligence, mistaking knowledge found on the Internet for our own.

The only effective way I have found to recall academic papers and articles found online is to print them out, mark them with a highlighter and take copious notes.

Another thing to bear in mind is that so-called cognitive offloading reinforces dependency on technology, which might explain why some AI companies now want people to hand off even more information, with one even calling for humans to “embrace forgetfulness.”

Of course, Cassandras have bemoaned the deleterious impacts of technology for centuries, while techno-optimists cite the pocket calculator as just one example of equipment that made certain tasks easier but did not turn our brains to mush.

However, as this paper published in Frontiers in Psychology noted, calculators have limited functionality, while AI chatbots encompass a much broader cognitive range “from general knowledge, problem-solving, emotional support, up to creative tasks.”

If students come to rely on machines not just to retrieve facts but to think for them, it might not just be memory that suffers: Cognition and creativity could atrophy, too. A once steady rise in IQ scores known as the “Flynn effect” has begun to fade in several countries, albeit the causes are debated.

Governments are still in the early stages of thinking about AI’s role in education. I am sure there would be benefits that augment human learning, while some of the negative effects I have described can be mitigated. However, we do not need to reinvent the wheel: In an era of conspiracy theories and misinformation, it is even more vital that we humans have a firm grasp of basic facts.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies in Europe. Previously, he was a reporter for the Financial Times. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

As the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) races toward its 2027 modernization goals, most analysts fixate on ship counts, missile ranges and artificial intelligence. Those metrics matter — but they obscure a deeper vulnerability. The true future of the PLA, and by extension Taiwan’s security, might hinge less on hardware than on whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can preserve ideological loyalty inside its own armed forces. Iran’s 1979 revolution demonstrated how even a technologically advanced military can collapse when the social environment surrounding it shifts. That lesson has renewed relevance as fresh unrest shakes Iran today — and it should

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged