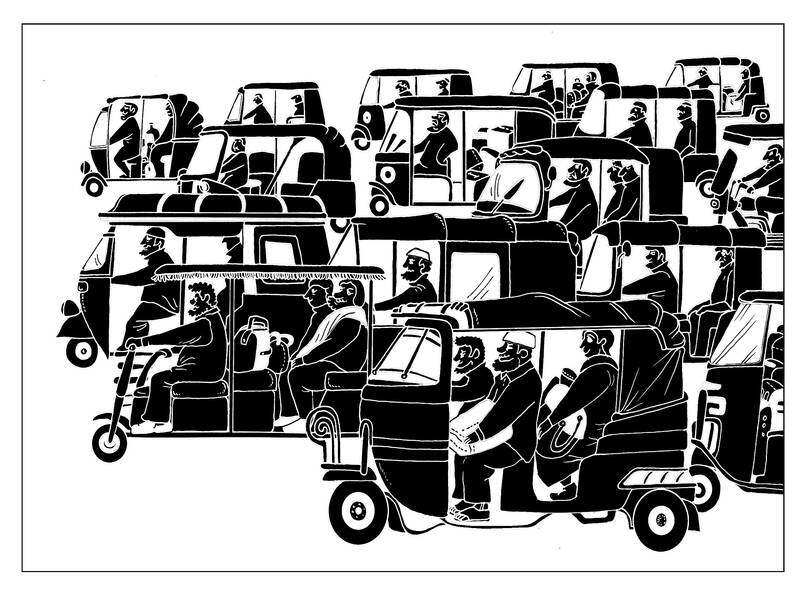

Life moves pretty fast. That is especially true in India’s booming cities.

A decade ago, the country’s iconic auto-rickshaws had three wheels and a diesel engine. Battery-powered versions existed, but only enough to be seen as a novelty and unregulated threat. Officially, only 12 e-rickshaws were sold nationwide in 2014 (The true number would be higher, but the unregulated nature of the industry meant that most sales were not captured in official statistics).

How far we have come. The place where road transport is shifting most rapidly to battery power is not Oslo or Shenzhen, but Delhi. E-rickshaws took a 54 percent share of India’s three-wheeler market last year, driven by zippy, longer-range models and running costs that are a fraction of petroleum-powered alternatives. Visiting the country last week, one of the first stops for Uber Technologies Inc chief executive officer Dara Khosrowshahi was to get behind the wheel of a Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd electric three-wheeler and promise an expansion into two and three-wheeled ride-hailing.

Illustration: Mountain People

Those betting India would come to the rescue of flailing global oil demand (it is reckoned to be the biggest source of consumption growth between now and 2030, outstripping even China) need to reckon with how things are changing on the streets.

There is no mystery why e-rickshaws have been taking over. Buy a Bajaj Maxima with an engine and you would pay about 3 rupees (US$0.04) per kilometer for diesel — a significant slice of earnings that average out about 10 rupees per kilometer. A Piaggio Ape E City with a lithium-ion battery charged at home, on the other hand, might cost just 0.27 rupees per kilometer. As a result, e-rickshaws are not just cleaner and quieter, they are more profitable, too. That is a decisive consideration for drivers who are usually rural migrants trying to get a foothold in the big city.

If this revolution was confined only to three-wheelers, it would not be much to get excited about. Auto-rickshaws are a highly distinctive part of India’s road fleet, but not a very significant one. Trucks and cars are sold in far greater numbers, while more than 70 percent of vehicle sales are two-wheeled scooters and motorbikes.

However, the hard financial logic that has caused e-rickshaws to take over is starting to play out on two wheels, too. Manufacturers are launching a slew of new models with price tags and performance to compete with conventional bikes and scooters that retail for less than 100,000 rupees. With gasoline prices up about a third thanks to the rise in crude since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, that could spark a stampede like the one that transformed the e-rickshaw market. Only about 5 percent of two-wheelers sold last year were battery-powered. McKinsey & Co forecasts that figure would hit 60 percent to 70 percent by 2030.

“The industry is going through a price war,” Hero MotoCorp Ltd emerging mobility unit head Swadesh Srivastava told an investor call on Feb. 10.

Hero’s main domestic two-wheeler rival, TVS Motor Co, plans to offer models this year in every segment of the market, from premium to basic, and to expand its dealership network from 400 cities to 800 over the three months through March.

That could start to cause real pain for oil producers who have mostly shrugged off the e-rickshaw revolution. Only about 1.4 percent of India’s gasoline and diesel is consumed by three-wheelers, but two-wheelers gulp down about 17 percent of the total. The International Energy Agency’s latest estimates for the country’s oil demand are already being trimmed. Its latest report reckons 6.6 million barrels a day would be consumed in 2030 — above 5.5 million barrels last year, but well down from a central forecast of 6.8 million daily barrels in its global outlook on October last year.

However, the real prize lies beyond two wheels. The biggest polluters by far on India’s roads are not two or three-wheelers but trucks, which consume nearly half of all gasoline and diesel. Trucks are normally seen as the hardest segment for electric vehicles (EV) to crack. The biggest rigs are simply too energy-hungry to be powered by a battery. Even smaller ones are worked hard day and night for thin margins, making it difficult to spare the time to charge up their power packs.

Even here the sands are shifting. Tata Motors Ltd launched its first small electric truck in 2022 while Mahindra, the leading e-rickshaw producer, is planning to release a range next year. Truck owners, like rickshaw drivers, are intensely sensitive to the combined costs of purchase, refueling and maintenance — and manufacturers seem on the cusp of hitting their sweet spot.

Current e-trucks work out cheaper than diesel models once you have been operating them for five to seven years, Ashok Leyland Ltd managing director Shenu Agarwal on Feb. 6 told investors.

“If we can bring it down below five years, then it will start making much more sense,” he said.

In the US and Europe, the shift to EV was a top-down affair, best exemplified by Elon Musk’s 2006 promise to start by building an electric sports car and then use the profits to make progressively more affordable mass-market vehicles. Well-heeled drivers cannot get enough of luxury EVs like Porsche AG’s Taycan and Rolls-Royce’s Spectre, while the rest of us are waiting in vain for the sub-US$30,000 city cars we were promised.

India seems to be moving in the opposite direction. Electrification of conventional cars and SUVs is still moving at a snail’s pace, with battery cars winning just a 2 percent share of four-wheelers last year. That does not matter much in a market that is dominated by smaller vehicles and cost-conscious drivers. When the EV revolution arrives in India, it would come from the bottom up.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. Previously, he worked for Bloomberg News, the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

As the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) races toward its 2027 modernization goals, most analysts fixate on ship counts, missile ranges and artificial intelligence. Those metrics matter — but they obscure a deeper vulnerability. The true future of the PLA, and by extension Taiwan’s security, might hinge less on hardware than on whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can preserve ideological loyalty inside its own armed forces. Iran’s 1979 revolution demonstrated how even a technologically advanced military can collapse when the social environment surrounding it shifts. That lesson has renewed relevance as fresh unrest shakes Iran today — and it should

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged