Ridley Scott’s Napoleon promises to be the highlight of the cinematic season. Scott has already proven he is a master of the historical epic with Gladiator. Both the lavish trailers and reviews suggest the new film would have all the ingredients of a blockbuster: cavalry charges, military parades, cannon fire, hand-to-hand conflict and blood-thirsty revolutionary crowds. Who could ask for more at Thanksgiving?

The two-and-half-hour extravaganza also provides people with an excuse to revisit one of the thorniest of all historical questions: What is the role of great men and women in history? Is history made by unique individuals pursuing their dreams? Or is it the product of vast impersonal forces? This is more than just an idle question. The answer people give shapes the sort of history taught in schools and universities. It also influences people’s approach to civic life: The more people emphasize the role of human agency, the more they would be inclined to be active citizens.

The question of Napoleon’s role in history divided two of the greatest writers of the 19th century. Thomas Carlyle used Napoleon to illustrate his contention that “the history of the world” is essentially “the biography of great men.” Leo Tolstoy, by contrast, presented him as a silly little man who was swept along by the majestic forces of history. Carlyle the historian thought the proper attitude to the past was to marvel at the way great spirits shape events. Tolstoy the novelist thought the proper attitude was to look beneath individuals and events to see more profound currents at work.

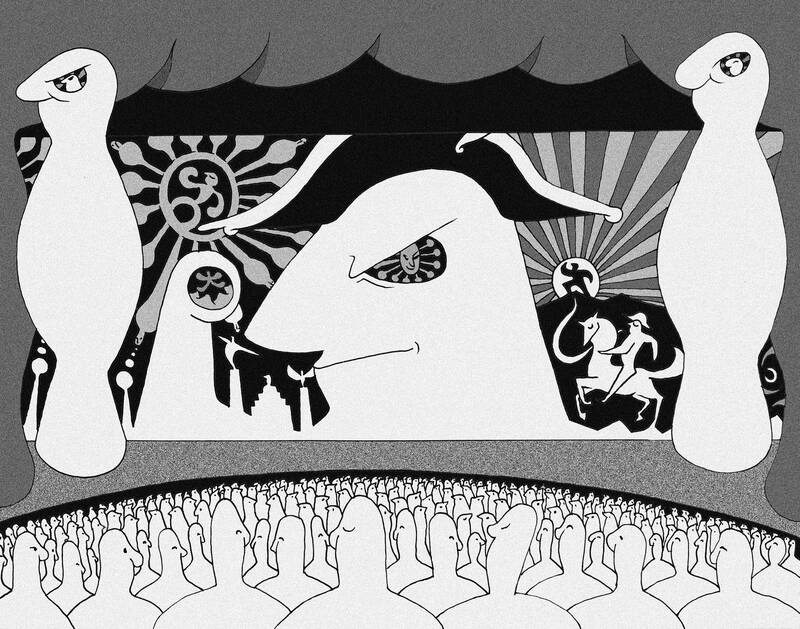

Illustration: Mountain People

Since then, the public has tended to side with Carlyle and the historical profession with Tolstoy. Napoleon is reputedly the subject of more biographies than anybody other than Jesus (the first full-scale biography was written before his 30th birthday). He is also the subject of numerous previous films, starting with one of the first films ever made, Louis Lumiere’s 1897 short, and including one of the masterpieces of silent cinema, Abel Gance’s Napoleon.

However, most historians have generally turned away from Napoleon the man, not to mention Napoleon the lover, and focused instead on the deeper currents of history: the mood of the masses, the price of grain or the logic of imperialism.

Edward Hallett Carr’s classic What is History? — a set-text for generation upon generation of Oxbridge history candidates — provides a sense of the contempt that serious historians have for the “great man” theory. Carr described this view of history as “the Bad King John and Good Queen Bess view” and argued that it belonged to the view of historiography adopted by primitive peoples and children. It might just about be fit for the nursery, but it was certainly unfit for the seminar room where serious historians discussed social forces and economic trends.

Carr devoted most of his professional life to producing a 14-volume favorable history of Soviet Russia, an opus that combined credulity and dullness in equal measures.

Carr’s disdain for the “great man” theory was reinforced by interlocking historiographical fashions. Marxist historians such as Eric Hobsbawm and Edward Palmer Thompson promoted “history from below” — that is, the history of ordinary people rather than namby-pamby elites. French historians such as Fernand Braudel focused on “anonymous, profound and silent history” rather than that of mere events. Braudel’s two-volume The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II had a great deal to say about the sea and almost nothing about Philip.

It was also reinforced by seemingly discordant intellectual tendencies. Political scientists downplayed the role of individuals because they wanted to prove that their subjects were predictive sciences. What is the point of all that tedious quantification if fate can be changed by the whim of any one person? And post-structuralist theorists such as Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault tried to write individuals out of history in their pursuit of the deeper structures of power.

The historians made a substantial point — that individuals do not make history just as they please but do so in the context of established power relations. Alexander the Great could not have conquered the known world if his father had not been the most powerful king in Greece. Napoleon would not have been able to seize control of France if a popular revolution had not swept aside the old regime and plunged the country into anarchy, but structural determinism can go too far by emptying history entirely of agency and personality.

Consider a few questions. Would Britain have stood firm against Nazi Germany if Lord Halifax had become prime minister rather than Winston Churchill, as many leading Conservatives wanted? Would the 1980s have gone as they did in Britain if Ted Heath had continued to lead the Conservative Party? Or would Singapore be the economic powerhouse that it is today if Lee Kuan Yew (李光耀) had not taken it in hand?

There are certain moments in history — when wars break out, when regimes break down — that make room for great individuals. Paradoxically, many great men and women feel that they are nothing more than agents of something bigger than themselves: Churchill talked about walking hand-in-hand with destiny, and Bismark about grasping the hem of history’s cloak and walking with him a few steps, but in fact, they can also change the direction of events.

Great leaders are change-makers precisely because they mobilize human qualities that cannot be reduced to a social “force” or an “economic” factor: determination, charisma, vision, imagination, even deceit. Churchill inspired faith because he refused to acknowledge the possibility of defeat despite Britain’s parlous position. Charles de Gaulle restored France’s postwar position because he revived the country’s belief in itself by spinning a tale of glory. Lee Kuan Yew turned Singapore into a hub of the global economy through sheer force of will and vision. “What seems inevitable becomes so by human agency,” as Henry Kissinger remarks in Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy.

Napoleon remains the perfect example of the ability of a single individual to change the course of history, so much so that, to this day, ambitious young MBA students dream of becoming the Napoleon of finance or retailing. He certainly came along at the right time — when the revolution was running out of control and people craved order and national reunification, but his idiosyncratic decisions also shaped events in ways that could not have been predicted. If Napoleon’s remarkable military talent turned an obscure Corsican into the master of Europe, his disastrous vanity also drove him to embark on a doomed campaign to conquer Russia.

He is also the perfect example of the mixture of good and bad that resides in the souls of the most famous leaders. There are plenty who have been wholly bad: Adolf Hitler most obviously, but also Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Pol Pot and many others.

However, nobody qualifies as wholly good. Napoleon the Great justifies both Goethe’s description of him as being “in a permanent state of enlightenment” and Madame de Stael’s as being “an oriental despot, a new Attila, a warrior who knows only how to corrupt and annihilate.”

The new historians who now control what history is taught in universities and schools have done much good. They have rescued the history of regular people from obscurity. They have revealed many of the hidden structures of power and influence that drive day-to-day events, but they have gone too far in downplaying the role of individuals or denouncing the exercise of moral judgement. It is time to push back.

Putting the great individual back at the heart of history teaching is not only good for our collective education in citizenship, it also teaches us that history is a matter of choices rather than a fait accompli, and that those are moral, not just technical, choices. It is also good for exciting young people’s interest in the past: Just try contemplating Napoleon’s rise from the periphery of French civilization to the summit of European power, and fail to be enthralled.

Adrian Wooldridge is the global business columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. A former writer at The Economist, he is author of The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them

More than 30 years ago when I immigrated to the US, applied for citizenship and took the 100-question civics test, the one part of the naturalization process that left the deepest impression on me was one question on the N-400 form, which asked: “Have you ever been a member of, involved in or in any way associated with any communist or totalitarian party anywhere in the world?” Answering “yes” could lead to the rejection of your application. Some people might try their luck and lie, but if exposed, the consequences could be much worse — a person could be fined,

Xiaomi Corp founder Lei Jun (雷軍) on May 22 made a high-profile announcement, giving online viewers a sneak peek at the company’s first 3-nanometer mobile processor — the Xring O1 chip — and saying it is a breakthrough in China’s chip design history. Although Xiaomi might be capable of designing chips, it lacks the ability to manufacture them. No matter how beautifully planned the blueprints are, if they cannot be mass-produced, they are nothing more than drawings on paper. The truth is that China’s chipmaking efforts are still heavily reliant on the free world — particularly on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

Last week, Nvidia chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) unveiled the location of Nvidia’s new Taipei headquarters and announced plans to build the world’s first large-scale artificial intelligence (AI) supercomputer in Taiwan. In Taipei, Huang’s announcement was welcomed as a milestone for Taiwan’s tech industry. However, beneath the excitement lies a significant question: Can Taiwan’s electricity infrastructure, especially its renewable energy supply, keep up with growing demand from AI chipmaking? Despite its leadership in digital hardware, Taiwan lags behind in renewable energy adoption. Moreover, the electricity grid is already experiencing supply shortages. As Taiwan’s role in AI manufacturing expands, it is critical that