As Thai politicians jockey for positions ahead of elections that must be called by March next year, focus is turning to how the next leadership will manage risks including sky-high prices, a bloated budget deficit and the highest level of household debt in the region.

The tepid pace of recovery in Southeast Asia’s second-largest economy will be front and center for voters as authorities grapple with the fastest inflation in 14 years, the baht’s plunge to the lowest since 2006 and household debt at 88 percent of GDP.

“While the recovery in tourism will help support growth over the next two to three years, an aging population and high household debt places Thailand as the laggard in the region,” said Lee Ju Ye (李居業), an economist at Maybank Investment Banking Group. “These are challenges that will not be easily resolved even with a new prime minister.”

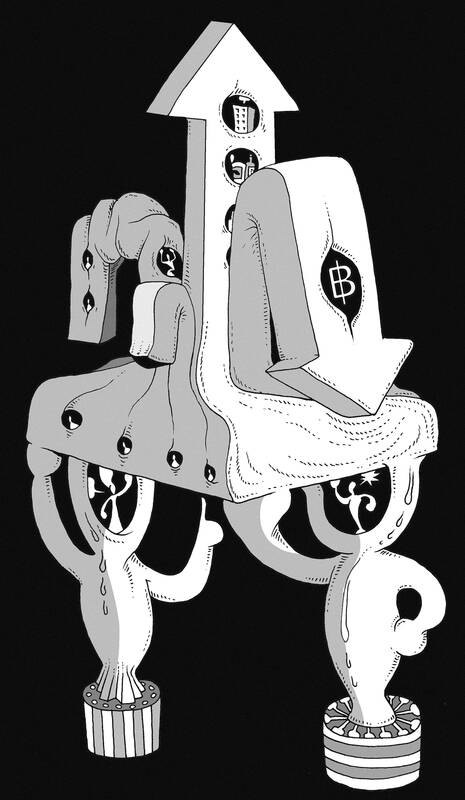

Illustration: Mountain People

Tourism makes up 12 percent of GDP.

Thai Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha, who last week won a favorable court ruling on a tenure dispute, has seen his popularity slide, reflecting the growing public disappointment with his government’s efforts to rebuild an economy that is still reeling from the COVID-19 pandemic and lagging peers in the region.

Paetongtarn Shinawatra, daughter of former Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, and Thai lawmaker Pita Limjaroenrat from the opposition Move Forward Party are top choices for prime minister in recent opinion polls.

Here are some of the economic challenges the next administration are likely to inherit:

RISING COSTS

Thailand’s recovery has been uneven, with those in export industries bouncing back faster while low-earners and tourism workers struggle amid inflation of more than 7 percent, triggering the first price hike in a decade among noodle makers and the first increase in minimum wage since 2020. Lately, the nation has to worry about the impact of floods, too.

The Bank of Thailand is expected to keep tightening rates although at a gradual pace compared with peers in the region. Lenders also have subsequently raised rates. The central bank has said price gains should cool to within its target by the middle of next year.

Net-oil importer Thailand continues to subsidize diesel, electricity and cooking gas. The Cabinet extended some of the support until Nov. 20, mindful of the pain on consumers, which is also exacerbating household debt.

ELEVATED DEBT

Household debt has jumped by 1.1 trillion baht (US$29.5 billion) to almost 90 percent of GDP from 80 percent before the pandemic. Although the ratio eased slightly in the second quarter, it remains the highest in Southeast Asia, making it tougher for the government to stimulate the economy. In the past, frustration with debt has sparked protests among farmers.

“Slower growth and higher inflation are exacerbating household debt and inequality,” said Pipat Luengnaruemitchai, chief economist at Bangkok-based Kiatnakin Phatra Securities.

These problems, if unresolved, could unleash more political and economic woes, he said.

Record Deficit

The government has spent about US$5.5 billion to subsidize energy prices, and the latest extension is expected to increase the bill by another 20 billion baht.

The budget gap ballooned to a record 700 billion baht in the fiscal year that ended last month, compared with 450 billion baht in 2019.

“We have exhausted all the fiscal ammunition during COVID with relief schemes and cash handouts,” said Kiatanantha Lounkaew, a lecturer of economics at Thammasat University.

On the brighter side, borrowing for the fiscal year that started this month was set at 1.05 trillion baht, substantially lower than the record 1.8 trillion baht in fiscal 2021.

BAHT VOLATILITY

The baht has lost 20 percent since the end of 2020. While this might be good for exports and tourism, the volatility hits investors and consumers.

There had been calls on the central bank to reconsider a hands-off stance as the baht depreciates. The Federation of Thai Industries, the nation’s top business group, said companies want a stable baht to prevent inflation from squeezing their profit margins.

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them

More than 30 years ago when I immigrated to the US, applied for citizenship and took the 100-question civics test, the one part of the naturalization process that left the deepest impression on me was one question on the N-400 form, which asked: “Have you ever been a member of, involved in or in any way associated with any communist or totalitarian party anywhere in the world?” Answering “yes” could lead to the rejection of your application. Some people might try their luck and lie, but if exposed, the consequences could be much worse — a person could be fined,

Xiaomi Corp founder Lei Jun (雷軍) on May 22 made a high-profile announcement, giving online viewers a sneak peek at the company’s first 3-nanometer mobile processor — the Xring O1 chip — and saying it is a breakthrough in China’s chip design history. Although Xiaomi might be capable of designing chips, it lacks the ability to manufacture them. No matter how beautifully planned the blueprints are, if they cannot be mass-produced, they are nothing more than drawings on paper. The truth is that China’s chipmaking efforts are still heavily reliant on the free world — particularly on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

Keelung Mayor George Hsieh (謝國樑) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) on Tuesday last week apologized over allegations that the former director of the city’s Civil Affairs Department had illegally accessed citizens’ data to assist the KMT in its campaign to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) councilors. Given the public discontent with opposition lawmakers’ disruptive behavior in the legislature, passage of unconstitutional legislation and slashing of the central government’s budget, civic groups have launched a massive campaign to recall KMT lawmakers. The KMT has tried to fight back by initiating campaigns to recall DPP lawmakers, but the petition documents they