When Sun Myung Moon, the South Korean founder of the Unification Church, needed money for its extensive spiritual and business ventures he would look to Japan, according to some former members.

“Senior officials would tell us he needed hundreds of millions of dollars and that Japan had to pay,” said Masaki Nakamasa, a Kanazawa University professor who was a member of the church for 11-and-a-half years until 1992.

Moon, a self-proclaimed messiah, died in 2012, but church doctrine tells its Japanese members they need to atone with donations for atrocities perpetrated during their country’s 1910-1945 occupation of Korea. According to church dogma, Japan is an Eve nation that, by consorting with the devil, betrayed Korea, portrayed as Adam.

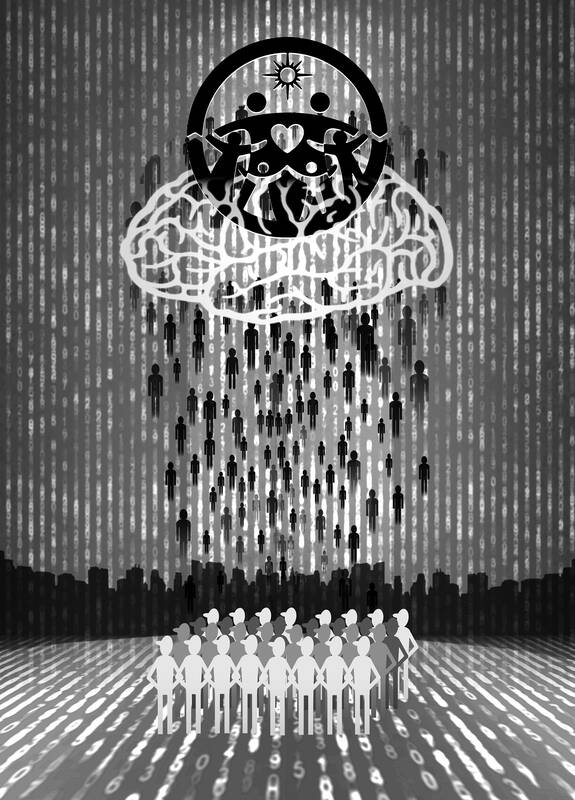

Illustration: Yusha

The Unification Church treated Japan like “an economic army” to raise donations, said Kwak Chung-hwan, Moon’s deputy until the late 2000s, who said the organization should apologize for the excesses of its leadership in the country.

In a statement, the church dismissed Kwak’s comment, saying he had discredited the organization and its followers.

While dozens of ex-members in Japan have sued the church since the 1980s over its fundraising, many former followers have hesitated until now to discuss their experiences publicly due to social stigma and fear of repercussions from their families.

The assassination of former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe in July opened a national debate over the Unification Church and has shone a spotlight on its close ties with the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

The suspect in the killing, 41-year-old Tetsuya Yamagami, accused the church of impoverishing his family, police said. In social media posts before the killing, he blamed Abe for supporting the religious group.

Starting with Abe’s grandfather former Japanese prime minister Nobusuke Kishi, the church openly cultivated relations with LDP leaders, based on their shared opposition to communism. Abe, like many other LDP lawmakers, spoke at church-related events and his government removed the church from a list of organizations monitored by the Public Security Intelligence Agency.

Since Abe’s killing, Japanese media have exposed ties between the church and dozens of LDP lawmakers.

Using information available on legislators’ Web sites and sources including videos posted online by the church, Reuters identified at least 65 LDP lawmakers — including Abe and 23 from his right-wing faction — who attended church events, sent congratulatory messages, paid membership fees, accepted political donations from its affiliates, or received election help.

Reuters also spoke with seven former Unification Church followers who described how their families were burdened with heavy donations. Five of them said church officials instructed them to vote for LDP candidates at elections.

“Our lives were worth less than our votes,” said one former church member, who said she was in hiding from her churchgoing mother and who posts online under the alias Keiko Kaburagi.

She said that she did not condone Yamagami’s actions, but could “understand how he felt” toward the LDP.

The blogger, like four other former church members interviewed by Reuters, asked not to be identified to avoid possible harassment.

The Unification Church says it no longer accepts donations that cause financial hardship and has curtailed aggressive “spiritual sales” of church goods after convictions for the practice a decade ago prompted its then-leader in Japan to resign.

The church says its political arm, the Universal Peace Federation (UPF), has courted lawmakers and most of them are from the LDP because of its ideological proximity, although it has no direct affiliation to the party.

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s emphatic win in July’s upper house elections — days after Abe’s shooting — was supposed to tighten his grip on the LDP, still dominated by the ex-prime minister’s supporters.

Instead, revelations over the LDP’s links to the church and his decision to grant Abe, Japan’s longest-serving post-war leader, a rare state funeral have triggered a crisis. An opinion poll published by Japan’s biggest daily, the Yomiuri Shimbun, on Monday last week showed that more than half of respondents opposed the funeral honors.

Five of the former followers interviewed by Reuters said the church directed its members to vote for LDP lawmakers who opposed LGBT rights and promoted traditional family values in line with church doctrine.

“Church leaders tell members at gatherings or through online messengers to vote for LDP candidates,” one second-generation member said.

The 20-something office worker asked not to be identified because their parents — who were married at a mass church ceremony — remain senior members.

The church says that it is does not give political guidance to members, which is done instead by the UPF.

Three current members interviewed by Reuters at its headquarters in Tokyo said that they were encouraged to vote in the upper house election for an LDP candidate, Yoshiyuki Inoue, a former political affairs secretary to Abe. Two of them said they did so.

Because of the proportional representation system used in upper house elections — whereby voters can cast their ballot for a candidate anywhere in Japan — targeted church votes can make a difference in tight races.

Kishida attempted to draw a line under the scandal with a Cabinet reshuffle on Aug. 10 that purged senior figures with links to the church, including former trade and industry minister Koichi Hagiuda, a member of Abe’s faction.

At a news conference the same day, Tomihiro Tanaka, the head of the Unification Church in Japan, said a push by Kishida to sever ties with the church would be unfortunate.

Despite Kishida’s effort to turn the page, a poll by the left-leaning Mainichi Shimbun on Aug. 22 showed that support for the government had fallen by 16 points from a month earlier to 36 percent.

In a news conference on Aug. 31, the prime minister went further, apologizing for the LDP’s ties to the church and promising to tackle them.

Yet Unification Church-connected lawmakers remain in Kishida’s administration, some in his Cabinet and dozens more as junior ministers. Any attempt by the prime minister at a deeper purge would risk upsetting a delicate political balance within the fractious LDP, political analysts say.

“He doesn’t really want any more dirt to be revealed,” said Koichi Nakano, a political science professor at Sophia University in Tokyo. “[Kishida] is trying to sort of lead people to think that what was in the past is in the past. The problem is it’s in the present.”

ALWAYS WORKING, STILL POOR

Hiroshi Yamaguchi, a member of the National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales, which pursues compensation cases against the church, estimates that the church still raises about ¥10 billion (US$69 million) a year in Japan, although that is down from ¥50 billion a year during the 1980s economic boom.

The church declined to say how much money it collects.

Officially known as the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, the church retains significant investments in media, schools, ginseng production, real estate and fishing operations. It is led by Moon’s widow, Hak Ja Han.

Four former members who spoke to Reuters described being asked to sell ginseng and other products door to door. Five said their families were coaxed into making donations they could ill afford.

“We were poor even though my father was always working,” said a social worker, 37, who left the church as a university student.

Their apartment in northern Japan had a kitchen, a bedroom she shared with her younger brother, and a room her parents used for sleeping and to display pictures, urns and other church artifacts they received as tokens for donations.

Now in Tokyo with her husband, she said she has minimal contact with her parents, who under church teachings she has condemned to hell.

“People don’t realize there are second-generation people like me everywhere,” she said. “We are just hidden.”

Her Twitter group with about 200 second-generation members has grown by about 50 people since Abe’s death, she said.

Its anonymity means former members can avoid the social stigma of being a follower, even a lapsed one.

Although the church says it has about 600,000 members in Japan, a spokesman said only about 100,000 are active and many second-generation members have drifted away from it.

One who dared to speak out publicly is Eri Kayoda, 28, who appeared on television after hearing that Yamagami’s mother had given the Unification Church US$730,000.

“My family was on the verge of collapsing because of donations,” she told Reuters.

Her public appearance, she said, enraged her mother.

Tanaka said after Abe’s killing that it had returned half of the donation made by Yamagami’s mother.

TARGETED

Some former members expressed anger that Japanese believers were targeted by the Unification Church for heavier donations. Fees published by the church in 2011 on a training Web site showed Japanese followers were charged five times more than South Koreans in tithes to free their ancestors from hell.

“We paid more because Japan has a bigger economy,” said Tsunefumi Harada, one of the three current followers who spoke to Reuters, defending the practice.

The church has become a target for nationalist sentiment. Its spokesperson played a video on his phone of right-wing vans decked with flags and nationalist symbols that turn up outside its Tokyo headquarters to blare denunciations from the loudspeakers on top.

Reuters could not independently verify the video.

The blogger, who uses the alias Kubagi, discovered the different pay scale when she married for a second time at one of the church’s mass ceremonies — a rare occurrence in a religion that forbids divorce, but for which she received an exception because her first husband beat her, she said.

Her first marriage at 21 cost US$10,000; the South Korean rate she got for the second six years later was one-10th of that, she said.

Now in her late 40s, she is still angry. She divorced and returned to Japan from South Korea in 2013 after Moon died.

Back in Tokyo with her two daughters, she does not expect to see her mother again unless she leaves the church. Between them, she reckons they gave the church about US$150,000, including US$5,000 for a plum blossom painting she has kept, even though it is worthless.

“It’s not the money I want back. I want the time the church took from me,” she said.

US President Donald Trump created some consternation in Taiwan last week when he told a news conference that a successful trade deal with China would help with “unification.” Although the People’s Republic of China has never ruled Taiwan, Trump’s language struck a raw nerve in Taiwan given his open siding with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggression seeking to “reunify” Ukraine and Russia. On earlier occasions, Trump has criticized Taiwan for “stealing” the US’ chip industry and for relying too much on the US for defense, ominously presaging a weakening of US support for Taiwan. However, further examination of Trump’s remarks in

As strategic tensions escalate across the vast Indo-Pacific region, Taiwan has emerged as more than a potential flashpoint. It is the fulcrum upon which the credibility of the evolving American-led strategy of integrated deterrence now rests. How the US and regional powers like Japan respond to Taiwan’s defense, and how credible the deterrent against Chinese aggression proves to be, will profoundly shape the Indo-Pacific security architecture for years to come. A successful defense of Taiwan through strengthened deterrence in the Indo-Pacific would enhance the credibility of the US-led alliance system and underpin America’s global preeminence, while a failure of integrated deterrence would

It is being said every second day: The ongoing recall campaign in Taiwan — where citizens are trying to collect enough signatures to trigger re-elections for a number of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — is orchestrated by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), or even President William Lai (賴清德) himself. The KMT makes the claim, and foreign media and analysts repeat it. However, they never show any proof — because there is not any. It is alarming how easily academics, journalists and experts toss around claims that amount to accusing a democratic government of conspiracy — without a shred of evidence. These

China on May 23, 1951, imposed the so-called “17-Point Agreement” to formally annex Tibet. In March, China in its 18th White Paper misleadingly said it laid “firm foundations for the region’s human rights cause.” The agreement is invalid in international law, because it was signed under threat. Ngapo Ngawang Jigme, head of the Tibetan delegation sent to China for peace negotiations, was not authorized to sign the agreement on behalf of the Tibetan government and the delegation was made to sign it under duress. After seven decades, Tibet remains intact and there is global outpouring of sympathy for Tibetans. This realization