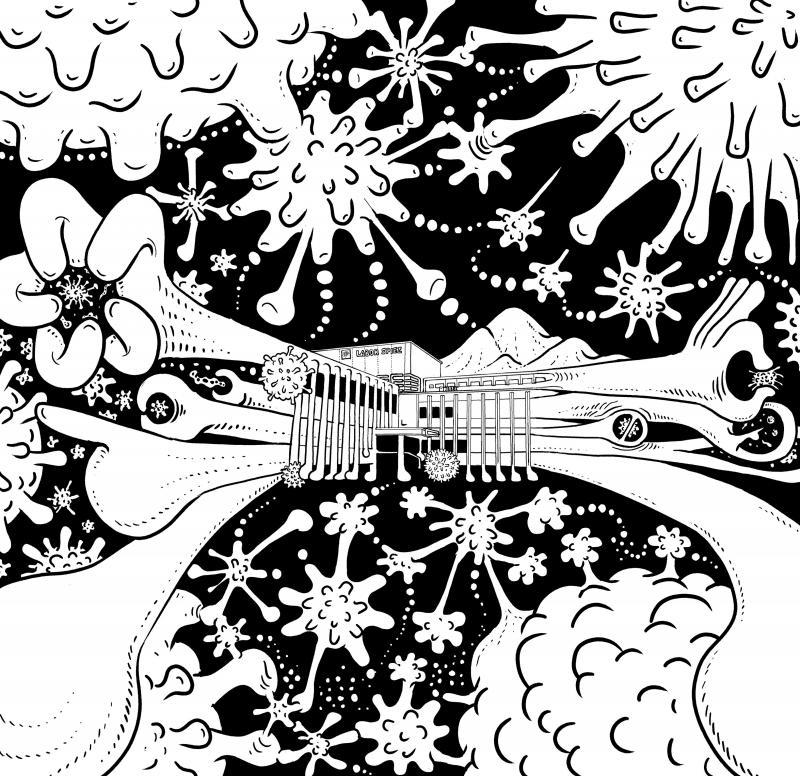

The setting is straight from a spy thriller: Crystal waters below, snow-capped Swiss Alps above, and in between lies a super-secure facility researching the world’s deadliest pathogens.

Spiez Laboratory, known for its detective work on chemical, biological and nuclear threats since World War II, was tasked last year by the WHO to be the first in a global network of high-security laboratories to grow, store and share newly discovered microbes that could unleash the next pandemic.

The WHO’s BioHub program was, in part, born of frustration over the hurdles researchers faced in obtaining samples of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, first detected in China, to understand its dangers and develop tools to fight it.

Illustration: Mountain People

About one year later, scientists involved in the effort have encountered hurdles.

These include securing guarantees needed to accept samples of SARS-CoV-2 variants from several countries, the first phase of the project. Some of the world’s biggest countries might not cooperate, and there is no mechanism yet to share samples for developing vaccines, treatments or tests without running afoul of intellectual property protections.

“If we have another pandemic like coronavirus, the goal would be it stays wherever it starts,” BioHub head of biology division Isabel Hunger-Glaser said.

Hence the need to get samples to the hub so it can help scientists worldwide assess the risk.

“We have realized it’s much more difficult” than originally thought, she said.

MOUNTAIN SAFETY

Spiez Lab’s exterior provides no hint of the high-stakes work inside. Its angular architecture resembles European university buildings built in the 1970s. At times, cows graze on the grassy central courtyard.

However, the biosafety officer in charge keeps his blinds shut. Alarms go off if his door is open for more than a few seconds. He monitors several screens showing security camera views of the labs with the greatest Biosafety Level (BSL) precautions. SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is studied in BSL-3 labs, the second-highest security level.

Samples of the virus used in the BioHub are stored in locked freezers, Hunger-Glaser said.

A system of decreasing air pressure allows clean air to flow into the most secure areas, rather than contaminated air flowing out to cause a breach.

Scientists working with SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens wear protective suits, sometimes with their own air supplies. They work with samples in a hermetically sealed containment unit. Waste leaving the lab is super-heated at up to 1,000°C to kill pathogens clinging to it.

Spiez has never had an accidental leak, the team said.

That reputation is a key part of the reason Spiez was chosen as the WHO’s first BioHub, Hunger-Glaser said.

The proximity to WHO headquarters, two hours away in Geneva, also helped. The WHO and Swiss government are funding the annual 600,000 Swiss franc (US$624,447) budget for its first phase.

Researchers have always shared pathogens, and there are some existing networks and regional repositories, but the process is ad hoc and often slow.

The sharing process has also been controversial, for instance when researchers in wealthy countries get credit for the work of less well-connected scientists in developing nations.

“Often you just exchanged material with your buddies,” Hunger-Glaser said.

Erasmus MC department of viroscience head Marion Koopmans said it took a month for her lab to obtain SARS-CoV-2 after it emerged in Wuhan in December 2019.

Chinese researchers were quick to post a copy of the genetic sequence online, which helped researchers begin early work, but efforts to understand how a new virus transmits and how it responds to existing tools requires live samples, scientists said.

EARLY CHALLENGES

Luxembourg was the first country to share samples of new SARS-CoV-2 variants with BioHub, followed by South Africa and Britain.

Luxembourg sent in the Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta variants of SARS-CoV-2, while the latter two countries shared the Omicron variant, the WHO said.

Luxembourg received Omicron samples from South Africa, via the hub, less than three weeks after it was identified, enabling its researchers to assess the risks of the now-dominant strain. Portugal and Germany also received Omicron samples.

However, Peru, El Salvador, Thailand and Egypt, all of which said earlier this year that they wanted to send in variants found domestically, are still waiting, chiefly because it is unclear which official in each country should provide the necessary legal guarantees, Hunger-Glaser said.

There is no international protocol for who should sign the forms providing safety details and usage agreements, she added.

The WHO and Hunger-Glaser said that the project is a pilot, and they have already sped up certain processes.

Another challenge is how to share samples used in research that could lead to commercial gain, such as vaccine development. BioHub samples are shared for free to provide broad access.

However, this creates potential problems if, for example, drugmakers reap profits from the discoveries of uncompensated researchers.

The WHO plans to tackle this in the long term and bring labs in each global region online, but it is not yet clear when or how this might be funded. The project’s voluntary nature could also hold it back.

“Some countries will never ship viruses, or it can be extremely difficult — China, Indonesia, Brazil,” Koopmans said, referring to the stance of those countries in recent outbreaks.

The project also comes amid heightened attention on labs worldwide after claims in some Western countries that a leak from a high-security Wuhan lab might have sparked the COVID-19 pandemic, an accusation China has dismissed.

Hunger-Glaser said that the thinking around emerging threats must change post-COVID-19.

“If it is a real emergency, [the] WHO should even get a plane” to transport the virus to scientists, she said. “If you can prevent the spreading, it’s worthwhile.”

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them

More than 30 years ago when I immigrated to the US, applied for citizenship and took the 100-question civics test, the one part of the naturalization process that left the deepest impression on me was one question on the N-400 form, which asked: “Have you ever been a member of, involved in or in any way associated with any communist or totalitarian party anywhere in the world?” Answering “yes” could lead to the rejection of your application. Some people might try their luck and lie, but if exposed, the consequences could be much worse — a person could be fined,

Xiaomi Corp founder Lei Jun (雷軍) on May 22 made a high-profile announcement, giving online viewers a sneak peek at the company’s first 3-nanometer mobile processor — the Xring O1 chip — and saying it is a breakthrough in China’s chip design history. Although Xiaomi might be capable of designing chips, it lacks the ability to manufacture them. No matter how beautifully planned the blueprints are, if they cannot be mass-produced, they are nothing more than drawings on paper. The truth is that China’s chipmaking efforts are still heavily reliant on the free world — particularly on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

Keelung Mayor George Hsieh (謝國樑) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) on Tuesday last week apologized over allegations that the former director of the city’s Civil Affairs Department had illegally accessed citizens’ data to assist the KMT in its campaign to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) councilors. Given the public discontent with opposition lawmakers’ disruptive behavior in the legislature, passage of unconstitutional legislation and slashing of the central government’s budget, civic groups have launched a massive campaign to recall KMT lawmakers. The KMT has tried to fight back by initiating campaigns to recall DPP lawmakers, but the petition documents they